The arrival of the COVID-19 vaccine, now with mandates at some workplaces, is causing a spike in workers seeking religious exemptions nationwide and among some of the Chattanooga area's biggest employers.

Jim Hopson, public relations manager for the Tennessee Valley Authority, said the federal utility company with COVID-19 has seen a spike from previous years in the number of religious and medical accommodation requests.

TVA employees must fill out a form to seek any kind of accommodation. Such requests are reviewed, and if they meet federal criteria, an accommodation is granted, Hopson said.

According to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, under Title VII, employers are to assume an employee's religious beliefs are sincerely held and provide employees an accommodation as long as doing so does not place "undue hardship" on the business.

However, the employer may pursue a "limited factual inquiry" and require additional information if there is doubt about the religious belief. A religious accommodation may be denied if the request is inconsistent with the beliefs of the religion or if the employer believes the accommodation is sought for non-religious reasons.

The employment commission states that objections centered around "social, political or personal preferences, or on nonreligious concerns about the possible effects of the vaccine, do not qualify as 'religious beliefs.'"

All major faiths in the United States support vaccinations, including the COVID-19 vaccine. There are slight nuances, such as the Catholic Church advising its followers to avoid vaccines derived from fetal tissue, given the church's stance on abortion, when other options exist. Similarly, some Muslim ethicists advocate avoiding vaccines that use a pork derivative, such as the shots for measles, mumps and rubella. Pigs are considered unclean in the faith and are avoided.

However, both faiths advise vaccination because the vaccines are far removed from the initial area of concern, and the potential for good outweighs such concerns.

Robert Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Dallas, has said "there is no credible religious argument" against receiving the vaccine.

Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote in his blog that Christians have a moral responsibility to seek the common good through immunization. Last month, the Fiqh Council of North America advised Muslims to receive the vaccine to "perform our duty of enjoining good and stopping evil."

Even religious denominations that tend to be more hesitant to endorse medical interventions, such as Jehovah's Witnesses and Christian Scientists, issued statements in support of vaccines and said adherents should make a personal decision.

While vaccine hesitancy has fallen in recent months, white evangelicals remain the most likely to avoid or refuse to receive the vaccine, according to a survey by PRRI–IFYC. White evangelicals also have the highest rate of vaccine refusal among religious groups surveyed, and the survey found white evangelical Protestants, white Catholics and white mainline Protestants were the religious groups least likely to respond to a faith-based appeal for vaccination.

The trend of religious exemptions may be better understood as a sociological phenomenon than a theological one, said M. Christian Green, senior fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University.

A divide between religious tenets and religious beliefs can emerge when people identify with a religious identity but do not attend a corresponding house of worship, Green said.

"When someone is not attending a church regularly and raises a religious exemption and has nothing from a clergy person to back them up, that's where people do start to wonder about the sincerity or the nature of the religious belief. And it's controversial." Green said "... You can't prescribe church structures or that people have that sense of ecclesiastical authority. But it's what raises questions."

Ben Kasstan, a medical anthropologist at the University of Bristol, England, has studied the factors leading to vaccine refusal among Orthodox and Haredi Jews in the United Kingdom and Israel. Those avoiding vaccination often do not consult religious leaders and typically cite safety concerns as the reason for their refusal, mirroring the reasons provided by non-Jews, Kasstan said.

"However, they consolidate their positions by citing Jewish legal codes to present non-vaccination as a religious imperative," Kasstan said in an email. "That in itself is an interesting question - how do we frame vaccine refusal as 'religious' when the majority of religious authorities themselves do not hold this position."

The Supreme Court under its conservative majority has largely sided with religious rights. Decisions - such as the First Amendment violation when the city of Philadelphia's foster care system refused to work with Catholic Social Service because the service would not work with same-sex couples - promoted the "free exercise" of religion clause. However, late last month, the court declined to block Maine's vaccine mandate, which required all hospital and nursing home staff to be vaccinated and did not offer a religious exemption.

Earlier this month, the Biden administration announced it would use Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations to force people working at companies with 100 or more employees to be fully vaccinated by Jan. 4 or be tested weekly for the virus. Exemptions are allowed for those who cannot receive vaccines due to a documented medical condition or sincerely held religious beliefs.

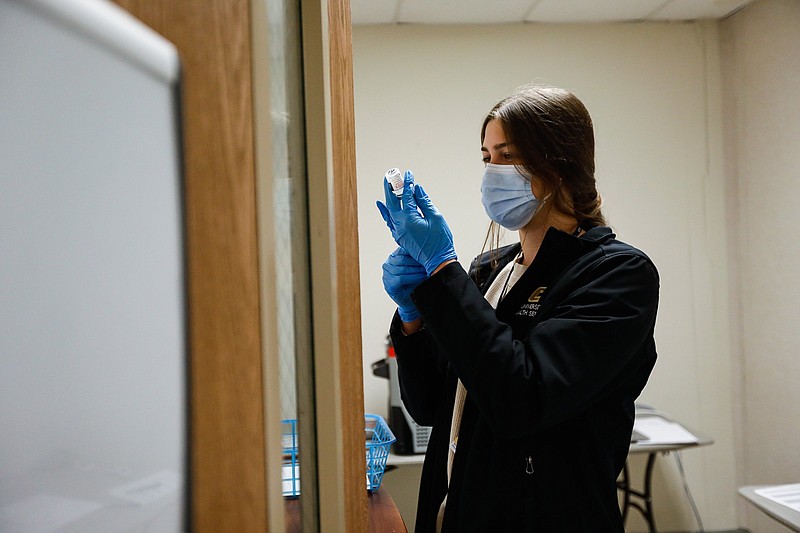

In August, CHI Memorial announced all employees would need to be vaccinated against COVID-19 by Nov. 1, mirroring a similar mandate the organization has for annual flu shots. Officials for the hospital system estimate less than 1% of employees resigned as a result of the rule.

Karen Long, communications manager for CHI Memorial, said the hospital system uses CommonSpirit Health to review requests for exemption.

"Each submission is reviewed by two independent reviewers," Long said in an email. "If the two independent reviewers' assessments were not completely aligned, a separate and third independent review occurred adding rigor to the process. Religious accommodations are granted in accordance with EEOC guidance."

Erlanger and Parkridge health systems are following similar guidelines under rules by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

"Erlanger is following the established processes from CMS for any applicable and legal exemptions for eligible staff," Blaine Kelley, public relations manager for Erlanger, said in an email. "Our current process does require that employees who wish to request a religious exemption complete a short questionnaire identical to the one provided by CMS, which is then reviewed by qualified people to determine if the employee's request is approved."

Parkridge did not respond to requests for comment this week.

Full data on the number of exemptions granted will be available once the CMS deadline for vaccination comes on Jan. 4, although the order is on hold pending litigation.

Contact Wyatt Massey at wmassey@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6249. Follow him on Twitter @news4mass.