VIDEO

This story is featured in today's TimesFreePress newscast.

Tennessee and Georgia were squabbling over land in the Chattanooga region long before the Peach State realized it might want to make a run at the Tennessee River.

In fact, much of that disputed land owned by Georgia sat smack in the heart of Chattanooga's downtown.

It was where the Chattanooga Public Library now sits, where the TVA complex stands, where the Edney Building and the Pickle Barrel anchor Market Street, where the Tallan Building and EPB's offices rise and where Miller Park offers downtown shade and respite.

"I heard the stories about it when I first came to Chattanooga 40 years ago," said former Mayor Ron Littlefield.

Littlefield and others remember brass plaques embedded in the sidewalks and engraved with this message: "Property of the State of Georgia, leased to the State of Tennessee."

Attorney Arvin Reingold, who eventually bought the Pickle Barrel property from Georgia, certainly remembers.

"I don't know what happened to the plaques," said Reingold.

"That pavement has been replaced a number of times," Littlefield said.

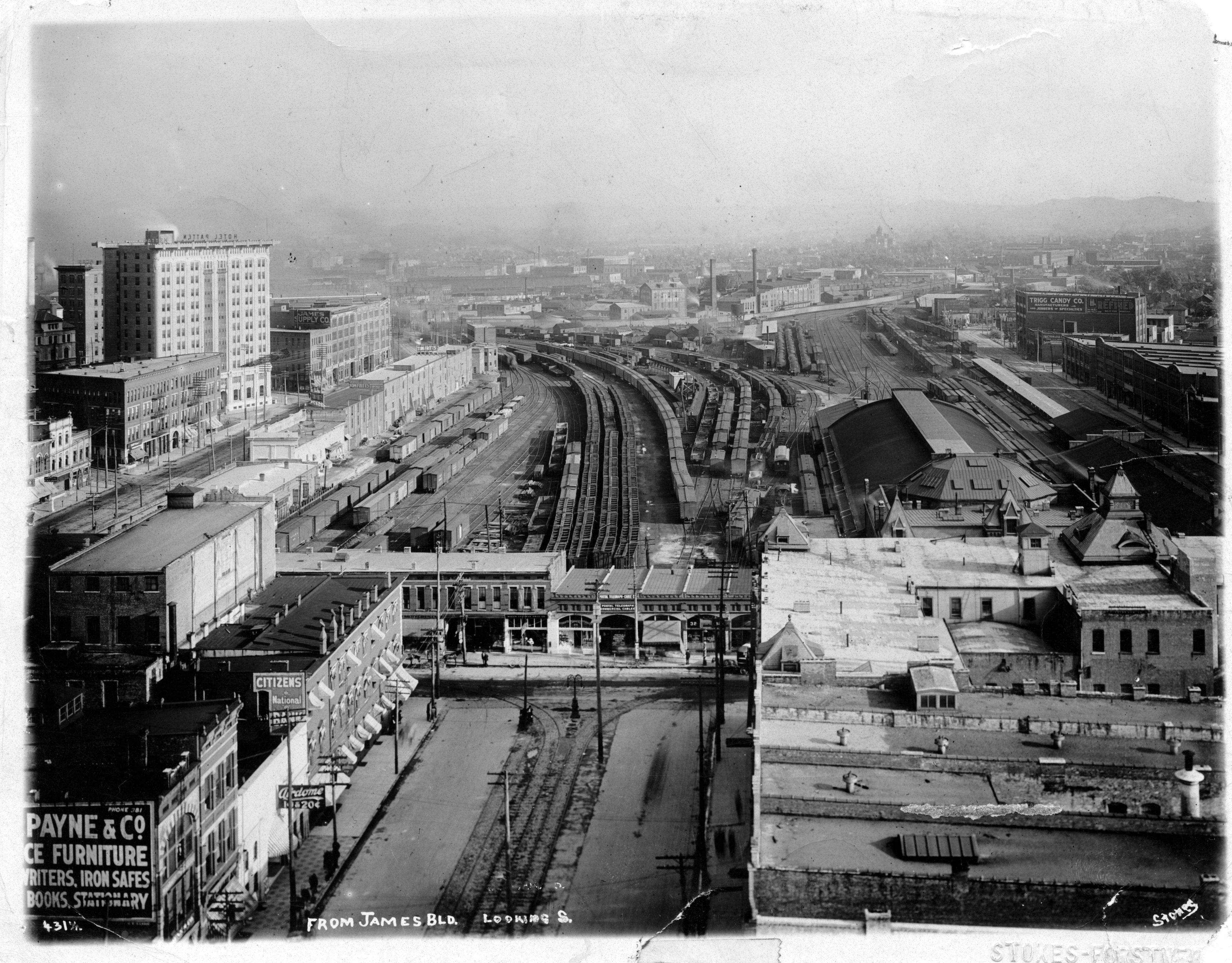

Georgia acquired the land more than a century ago when the Western & Atlantic Railroad was built to link Chattanooga with Atlanta. Georgia built the railroad and needed the property for switchyards and a terminal.

Through the years, the city and Georgia often sparred in an uneasy fellowship.

The Georgia-owned property was a nuisance to the city's growth, until city officials in the Roaring Twenties apparently saw a way through Georgia's blockade of buildings.

In 1926, Chattanooga Commissioner Ed Bass used a bit of trickery to speed along a Georgia secession. The sides were awaiting a court ruling on whether the city could use eminent domain to extend Broad Street from Ninth to Main Street -- right through one of Georgia's buildings.

"The city arranged to begin demolition for the construction of the road on a Saturday when the courthouse was closed and when obtaining an injunction to stop demolition would have been impossible," according to a news account.

"Crews worked Saturday night and all day Sunday. In the early hours of Monday morning, with the city commissioner on hand to direct them, cars drove through the new road while a band played 'Marching Through Georgia.'"

According to the history books, Bass and the City Commission were unhindered when they razed the new road's path.

Within a year Bass was elected mayor, and he won re-election four times.

Georgia eventually agreed to the city's use of the property to extend the road.

The legal case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that a state that owns property in another state is in the same position as a private property owner, and thus the city had the right to use eminent domain to acquire the Georgia property.

Over the years Georgia sold off parcels after the railroad yards were moved to Wauhatchie and the railroads abandoned the downtown tracks.

In 1961 Georgia lawmakers, who often made a yearly junket to Chattanooga to "inspect" the property and party, began talking of selling the state holdings here.

"We don't want to hamstring the future development of Chattanooga by retaining a large portion of its downtown business property," Rep. Chappelle Matthews, of Athens, told The Chattanooga Times that year. Matthews in 1961 was acting chairman of the Georgia House committee on state property.

By 1972, at the urging of then-Gov. Jimmy Carter, sales talk picked up. A Chattanooga Times story in August 1976 stated that three blocks in the heart of the city still belonged to Georgia and had been appraised at more than $1 million.

"Most of the Georgia property lies between Broad and Market streets and extends south from Ninth Street [now Martin Luther King Boulevard] across 10th and 11th streets to the L&N Railroad tracks. The state also owns the land on which the Edney building stands at the corner of 11th and Market, and recently sold the Hotel Plaza property at the intersection of Market Street and Georgia Avenue," the Times reported.

In February 1976, a news report stated that a bid of $51,000 on property containing the Plaza Hotel -- now the Pickle Barrel building -- was approved by the Georgia Properties Control Commission.

A second bid on the hotel property was rejected, as were bids on two other tracts in the downtown area.

"I guess I paid too much," Reingold quipped recently. He had two partners in the bidding.

A year later, the Chattanooga Chamber Foundation bought the block between Market and Broad and 10th and 11th streets for about $1 million, and the city in 1978 paid $460,000 for the block bounded by MLK, Broad, Market and 10th streets.

The next year, the city bought a 21/2 block tract south of 11th Street between Market and Broad, where it was known that TVA was considering a major office complex. That cost was $425,000.

In 2005, the Georgia State Properties Commission offered another sliver of land in the city for sale. The land, across King Street from the Development Resource Center and between ADM Milling Co. and a warehouse, appraised at $123,000 and sold for $150,000.

Georgia decided not to sell the remainder of the Western & Atlantic right of way extending from King Street to East Ridge and the state line.

On Friday, Paul Melvin, director of communication for the Georgia State Properties Commission, said Georgia still owns the remainder of that right of way, and a portion of the rail line is still very active.

Patrice Glass, a former historian with the Chattanooga History Center, said Chattanooga city fathers in the 1850s wanted the railroads to come to Chattanooga, and that's why they gave the railroad a lot of land.

Times, of course, have changed.

As for what happened to the brass ownership plaques? No one seems to know.

"They probably just got covered over," Littlefield said.

Maury Nicely, who leads walking tours around Chattanooga and is the Chattanooga History Center board president, said he's never seen one of the plagues.

"And I've done a little bit of looking," he said, noting that progress is often not a keeper of memories.

"I think it's probably an uphill battle to find one," he said.

Contact staff writer Pam Sohn at psohn@timesfree press.com or 423-757-6346.