Fast factsThe use of wiretaps nationwide has tripled since 2000, growing from 1,190 that year to 3,576 last year.The majority of wiretaps are used in drug investigations. Eighty-seven percent of all wiretaps were for such investigations, compared to 77 percent in 2003.Source: U.S. Department of Justice annual Wiretap Report

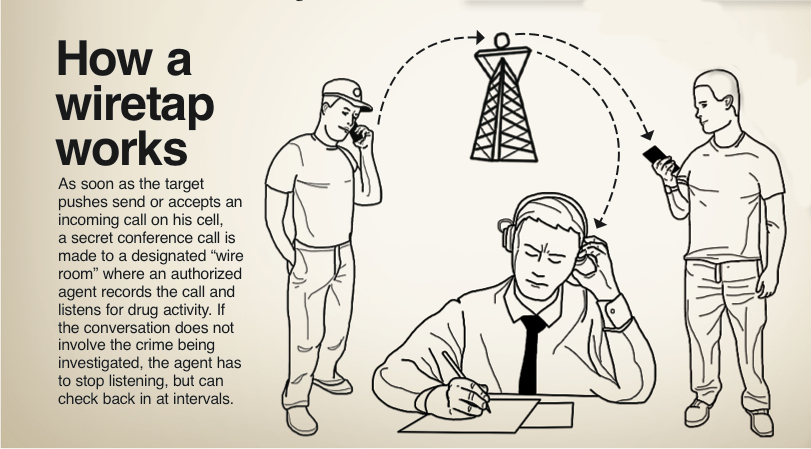

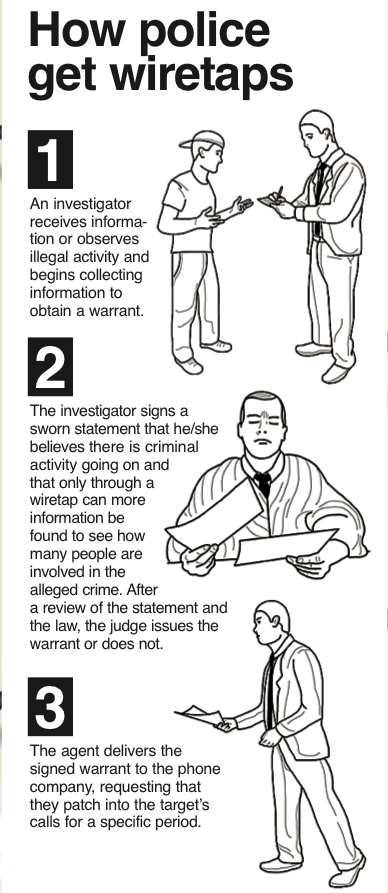

The secret of the cellThe explosion of cellphone use that began in the 1990s stymied investigators. They had no uniform way to tap into such calls. The way it was done with one company in Memphis could vary drastically, and cost more, than listening into calls in Chattanooga, for example.So, in 1994, they called Ben Levitan.A career telecommunications guy, Levitan was the right person to help build a standardized system so that any officer with a warrant could go to any phone company anywhere in the country, plug in and start listening.The process starts with a "pen register," an antique from the old days of copper wire. Back then, an agent would count the number of clicks on a rotary dial to decipher what number the target was calling.Nowadays that's all fed to the agent by computer. Agents analyze the numbers called to craft a theory about which callers are connected in the drug trade. They might also use surveillance and informants to build a case for a judge to grant a wiretap warrant.The agent takes the warrant to the phone company and, from then on, every call the suspect makes or takes is a secret conference call with an agent listening on the other end.And Levitan said cliche movie or television scenes where a frantic agent is yelling, "We need 30 seconds to get a trace!" are a myth. As soon as the target hits "send" on his or her phone, it's recording.Once a warrant is granted, the agents have to report back to the judge throughout the life of the warrant to ensure they're getting information on the suspected drug conspiracy. If not, the judge can cancel the wiretap at any time.Criminals often try to get around wiretaps by talking in code and using "burner phones," prepaid cell phones not registered to a user.

People shopping, running errands or dining in Chattanooga in recent years never had a clue that nearby, a major drug dealer was selling multiple ounces of cocaine that fueled the drug trade and influenced street gangs in the Scenic City and surrounding areas.

Juanzell Jenkins used vague text messages and coded cellphone talk to set up cocaine deals that often took place in parking lots of public places like Hamilton Place mall, Kanpai of Tokyo restaurant, McDonald's, Family Dollar and Big Lots. He bragged to friends that he bought brand-new Camaros with cash and controlled the violent local street gangs.

He ran counter-surveillance techniques to thwart police attempts to track him, dumped phones frequently to avoid being listened in on and cut off customers whom he suspected were talking to police.

But it was through some of those buyers that investigators would eventually research phone records, make controlled drug buys and later obtain the best evidence of all -- wiretaps of his calls.

Over four years, agents used those wiretaps and others to broaden their targets, pulling in name after name and eventually building to the 34-man cocaine conspiracy roundup made public by federal, state and local officials in November.

Investigators say Jenkins was a major source of cocaine in the region, buying quantities from Atlanta and wholesaling amounts to some of the nearly three dozen defendants who satisfied Chattanooga's cocaine appetite at street level. He and the others controlled much of the flow of cocaine in the Chattanooga area, investigators say.

The investigation involved at least a half-dozen wiretap warrants. Details in just two, obtained by the Times Free Press, reveal the names, dates and locations where 1- to 2-ounce drug deals went down between Jenkins and lower-level dealers who repackaged the drugs for individual sales.

In a letter from the Bradley County Jail to the Times Free Press this week, Jenkins disputed the evidence against him, saying the warrants were obtained illegally by agents using falsified information. If the accusation were borne out, prosecutors would be barred from using at trial any evidence gathered through the wiretaps.

Jenkins also claimed that some informants used against him lied or, in some cases, that interactions and conversations between him and the informants that are referenced in court documents never happened.

"My affidavit contains numerous contradicting statements concerning confidential sources and their alleged activity in the investigation," Jenkins wrote.

The November roundup of men, dubbed some of the "worst of the worst" area drug offenders by Chattanooga's former police chief, sparked a public outcry.

Family members pointed to the limited criminal histories of some of the men. A few had been convicted of violent crimes. Most had been involved in lower-level drug offenses.

But if allegations in the two warrants the newspaper examined from the four-year investigation are accurate, then prosecutors have mounds of detailed evidence against most of those charged in the conspiracy.

At least 20 of the 34 men indicted in the conspiracy already have pleaded guilty. Court testimony indicates that some were smaller players and were sentenced accordingly. Others, such as Jumoke Johnson Jr., have been called killers who are responsible for ongoing gang shootings.

In documents and hearings, defense attorneys argue that the wiretaps were not necessary, that the warrants were filled out improperly, or should never have been granted because they weren't needed. One such request to exclude wiretap evidence already has been denied. But the attorneys are still attacking the wiretaps because some of the most damning evidence comes from them.

Nationally, the use of wiretaps nationwide has tripled since 2000. They can help investigators tease out finer and finer threads in a drug or other criminal conspiracy. And, if a case goes to trial, the jury can hear the defendant condemn himself with his own words.

Local criminal defense attorney John Cavett, who has practiced for nearly three decades, said he thinks they provide "a pretty substantial shortcut" for investigators getting evidence.

"It takes a lot more time and manpower to put a major federal criminal case together using traditional investigative techniques," Cavett said.

Cavett was Jenkins' appointed attorney until last week, when U.S. Magistrate Judge Bill Carter reluctantly let Jenkins dismiss him. Jenkins asked to be assigned a new attorney, his third since charges were filed.

Retired federal prosecutor Gary Humble, now in practice, disagreed with Cavett. He said a warrant, executing the wiretap and monitoring it so it can continue under a judge's order requires a lot of time and manpower and isn't taken lightly.

One call leads to another

Jenkins' troubles started with a phone call.

In 2009, Cleveland, Tenn., police officers and Drug Enforcement Administration agents were investigating a Cleveland-based cocaine trafficking ring headed by Levar Williams. Wiretaps connected Williams with a dozen Cleveland drug dealers and helped convict them and send them to prison. Williams got 30 years.

The taps also revealed that Williams was getting his cocaine from Jenkins in Chattanooga. Rolling up the Cleveland ring yielded informants who worked for investigators collecting evidence Jenkins.

Over the next four years agents monitored Jenkins, following him in cars to see where he went and who he met, and setting up police-controlled drug buys. Agents supplied the cash that informants used to buy cocaine by the ounce, drugs that then were logged in as evidence.

And every moment of every call, every deal, was recorded.

A typical deal happened on June 21, 2011, when an informant, not named in court documents, called Jenkins at 10:30 a.m. seeking drugs to sell. Jenkins replied in code that he'd have to run it through the "car wash," slang for transforming powder cocaine into crack cocaine.

Jenkins told the source he could transform one ounce of powder cocaine for $1,000 into two ounces of crack because he "whipped" the drug, meaning he added ingredients to increase its volume, according to court documents.

The call, transcribed in court documents, set up the deal for a half-hour later.

Jenkins: So what you need?

Source: Well, I'm waiting them now. Well when I go back to work today. I was trying to see you this morning.

Jenkins: We can get together. Same ol story?

Source: Yeah ... uhh you ain't got no? man uhh ... the deal?

Jenkins: You talking about already going through the carwash?

Source: Yeah

About 30 minutes later Jenkins pulled his gray Volkswagen Touareg into the Big Lots parking lot at 3901 Hixson Pike, slightly more than two miles from his home.

The informant got into the passenger side of the Touareg, traded $1,000 for an ounce of crack and left.

Other warrants recorded Jenkins discussing drug deals with his brother Joe Jenkins, and led to Gerald Toney and Clifford Simpson, all charged in the drug conspiracy.

In a recorded call between the Jenkins brothers on May 14, 2012, the conversation is even more coded, referring obliquely to meeting up, "not missing the bus" in reference to getting drugs.

Juanzell Jenkins: (expletive deleted), if you can see something out of it holler at him again.

Joe Jenkins: If it's gonna be a day or two, but I don't want to miss the bus ...

Juanzell Jenkins: Believe me, you ain't gonna miss on the bus.

Joe Jenkins: Alright then.

High-ranking OG

Juanzell Jenkins wasn't modest about his place in the local drug trade hierarchy.

On March 19, 2012, Jenkins boasted about the high quality of his cocaine and how he'd gotten enough cash from dealing to buy two new Chevrolet Camaros, according to court documents.

He often drove from his Hixson home in the late morning or early afternoon to do drug deals in parking lots at businesses near Hamilton Place mall, such as Kanpai of Tokyo, or at locations along Brainerd Road, such as McDonald's. Occasionally he would meet with clients in Hixson, but almost never at his home.

Sources told investigators that Jenkins was high ranking, an "OG" or "original gangsta" in the Gangster Disciples street gang. The source said Jenkins claimed he was "calling shots" among the Gangster Disciples and his control of the good cocaine coming into the city gave him control of the Rollin 60s street gang.

Members of that Crips-affiliated gang have been linked to multiple shootings and killings, according to Times Free Press archives and court testimony.

But despite Jenkins' bragging, he wasn't fearless.

The year before, Jenkins had stopped selling drugs to a customer he thought was working with the police. He stopped returning that informant's calls, according to court documents.

On several buys, agents wrote in court documents, they had to break off following Jenkins because he was conducting counter-surveillance. They also said that in certain neighborhoods where some of the suspects lived, residents would watch for unfamiliar people and cars and warn drug dealers, jeopardizing the investigation.

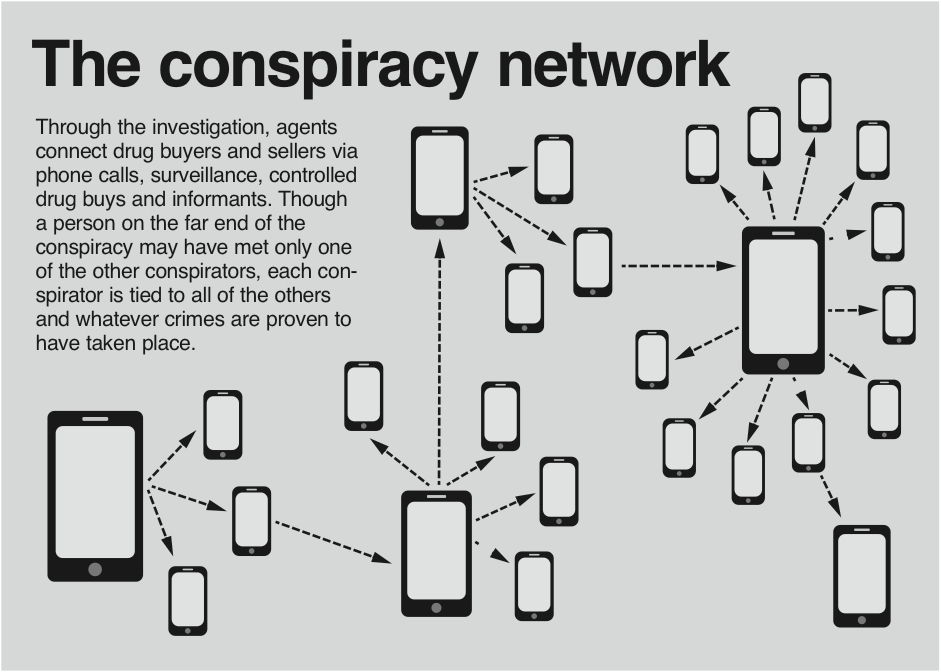

It's unclear from documents whether Jenkins was connected directly to all the defendants in the November roundup. But under drug conspiracy laws, a direct connection doesn't matter.

For example, a street dealer here who may have interacted with his midlevel drug connection can be linked to the major supplier in Atlanta under the law, even if the street dealer only ever met his local connection.

Those links give prosecutors leverage, allowing them to pressure lower-level defendants to plead guilty and testify to avoid the heavier punishments of those much further up the drug chain.

At least two of the 20 who have already pleaded have direct connections to drug deals with Jenkins -- Gerald Toney and Robert Stephon North, both smaller-scale drug sellers. Both men's conspiracy charges were dropped and they now face sentencing on a single count of narcotics distribution.

Necessary?

Defense attorneys for some of the men have challenged the use of wiretaps, saying they weren't needed to make the conspiracy case.

Humble said that's a common question with wiretaps. Basically, could investigators have gotten the information they needed without tapping the phone and encroaching on peoples' privacy?

Throughout the court documents obtained by the Times Free Press are arguments in both directions.

The agent asking for a tap warrant says that traditional methods such as camera surveillance, controlled drug buys and monitored phone calls -- when one party knows the call's being recorded but the other doesn't -- were not sufficient or practical in this case.

Each time wiretaps in this case yielded another suspect, the investigation continued. That's why such a wiretap investigation might go on for years, as it did with Jenkins and others.

But defense attorneys who have asked the trial judge to throw out wiretap-related evidence say the surveillance, controlled buys and monitored calls that agents used to obtain a wiretap warrant were sufficient by themselves.

Carter or, ultimately, U.S. District Judge Harry S. "Sandy" Mattice will likely rule whether the wiretaps were necessary -- if not, any eventual jury won't hear those voices on the phone setting up and carrying out major cocaine deals.

But Cavett said that in this court district it's "extremely rare" for judges to throw out wiretap evidence.

Contact staff writer Todd South at tsouth@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow him on Twitter@tsouthCTFP.