Background

Antibiotics are victims of their own success, scientists say. Before the 1940s, when penicillin began to be widely used, there was no treatment for most bacterial infections. “You got better on your own or you didn’t,” one doctor said. Many people didn’t.But in 1928, Scottish researcher Alexander Fleming noticed that a mold growing in his lab was killing some of the bacteria he was studying. He called it penicillin but wasn’t convinced it was very useful. It took until 1945 for other researchers to figure out how to produce penicillin cost-effectively, but once it went into mass production, its success was immediate. Other antibiotics were also soon discovered, and they proved to be hugely effective in preventing infections by wiping out the bacteria that caused them.

The headlines are growing scarier:

"Resistance to last-resort antibiotic has now spread across globe," New Scientist magazine said in an article last month.

"Apocalypse Pig: The Last Antibiotic Begins to Fail," was how National Geographic began a similar story, both reporting on a study in China that claimed that because of misuse by pig farmers, an antibiotic scientists had touted as their last hope against superbugs wasn't working.

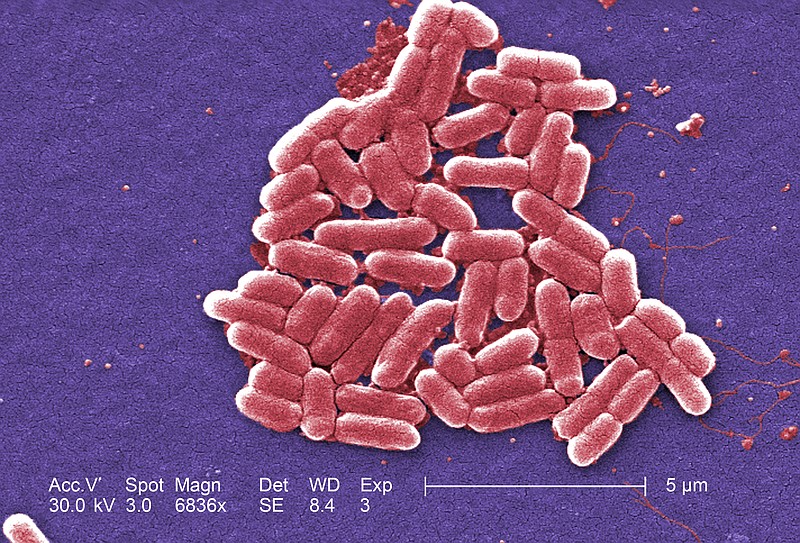

"Superbugs" is the name given to bacteria that have evolved to develop a resistance to antibiotics. If all antibiotics became ineffective, medical science would suffer a severe setback, scientists say.

"You have a young child who has an ear infection, many will require antibiotics," said Dr. Katherine Fleming-Dutra, an expert with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. "With urinary tract infections and with most surgeries, we give antibiotics. For C-sections, usually there will be an antibiotic given. People with cancer, on chemotherapy or radiation, where their immune system is weakened, we will give them an antibiotic."

If effective antibiotics are not available, then those common medical procedures would become much more risky, Fleming-Dutra said.

The growing threat of antibiotic resistance is a "ticking time bomb" that should be ranked alongside terrorism in terms of risk, England's chief medical officer, Sally Davis, has said.

In any population of bacteria, while the antibiotics will kill most, a few bacteria with slightly different characteristics will survive. Over time, they multiply and form a new strain that is resistant to the original antibiotic.

Every antibiotic ever discovered faces that same issue - the more it is used, the sooner new bacteria spring up that are resistant to it. But the pace at which new antibiotics have been discovered has slowed, while more and more superbugs have proliferated.

"We're not coming up with new classes of antibiotics nearly as fast as we used to," Fleming-Dutra said.

Fortunately, slowing the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics doesn't take any expensive technology. One of the biggest problems is overuse, because too many doctors are too quick to prescribe them, even when they aren't needed. Health care providers in Tennessee are among the worst offenders. According to the CDC, Tennessee ranks fifth in the U.S. in over-prescribing antibiotics, with a rate of 1,190 prescriptions per 1,000 people. Health care providers in Oregon, in contrast, prescribed an average of only 579 per 1,000 people - about half as much.

Why do doctors over-prescribe antibiotics? Often, because patients insist on getting them, said Sarah Fraser, who is heading up a campaign by health insurer BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee to persuade doctors to be more selective.

"One of the things that happens is that patients come in with an expectation of some kind of treatment," Fraser said. "Sometimes that treatment shouldn't involve antibiotics."

Doctors "worry about customer satisfaction," said the CDC's Fleming-Dutra. If they believe they need an antibiotic and don't get it, "patients will go somewhere else."

One of the worst conditions for overprescribing is the common winter chest cold or flu, that wheezing, coughing, nauseous, headachy feeling that just won't go away. Ninety percent of the time, that is caused by a virus and not bacteria, Fraser said. Antibiotics don't work at all against viruses.

Fraser's main weapon for the war on superbugs doesn't look all that impressive. It's a bag filled with alcohol wipes, Tylenol tablets, some tissues, a thermometer and Blistex lip ointment.

The kit is intended to give patients something they can take home in place of antibiotics. She and her staff hope to distribute more than 11,000 of the kits, mainly to primary care physicians, by the third week in January.

"The reasons we focused on physicians, is that antibiotic use starts in the outpatient setting to a large extent," Fraser said. "A lot of them are prescribed for things that need it and some for things that don't."

So what should you do in place of taking antibiotics?

First, don't get infected. Wash your hands, and try to avoid putting your fingers in your mouth, said Dr. Brent Campbell, a primary care physician with UT Erlanger Hixson Primary Care center. That means not "eating something finger-licking good, or biting on your nails," Campbell said.

Sneeze into your sleeve and not on your hands, he said. Eat healthy, take multivitamins and drink plenty of fluids.

And if your doctor does prescribe antibiotics, don't stop taking them, said Fraser.

"If somebody just takes the antibiotics until they feel better, that doesn't mean the infection is gone," she said. If any bacteria are merely weakened and survive, they may develop resistance.

"We're not on the brink of not having antibiotics to treat infection," Campbell said. "But we need to prepare now. There is a clear and present danger that is mildly surfacing, but it is enough that we need to be careful now so in the future we don't have a greater problem."

Fleming-Dutra is not as optimistic.

"We have been in a race against time in that as a new antibiotic is introduced, and it is used more frequently, the bacteria evolve and develop a resistance to it. We're just trying to stay a couple of steps ahead of it."

"There are some nightmare bugs out there," she said.

Contact reporter Steve Johnson at sjohnson@timesfreepress.com, 423-757-6673, on Twitter @stevejohnsonTFP or on Facebook at facebook.com/noogahealth.