When stroke patients are wheeled through the doors Erlanger Health System, they have just arrived on the frontier of U.S. stroke treatment.

Seconds matter, and patients are whisked down to a bustling, brain-saving operation. A 24/7 stroke team sprints patients into brain scanners within 10 minutes. A doctor snakes a device into a patient's leg that reaches deep inside the brain to retrieve a clot. A billion stem cells, stored at -180 degrees Fahrenheit in liquid nitrogen, are thawed and added to a stroke survivor's blood in an experiment meant to speed recovery.

STROKE STATISTICS

About 795,000 Americans each year suffer a new or recurrent stroke. That means, on average, a stroke occurs every 40 seconds. On average, someone dies of stroke every four minutes. Stroke kills more than 137,000 people a year. That's about one of every 18 deaths. It's the No. 5 cause of death. About 40 percent of stroke deaths occur in males, and 60 percent in females. Americans paid about $73.7 billion in 2010 for stroke-related medical costs and disability. Source: American Stroke Association

When doctors worldwide talk about the future of stroke treatment, they cast many predictions that are already day-to-day reality in Chattanooga. Erlanger, best known as the region's public safety-net hospital, is also home to the Southeast Regional Stroke Center, which is spearheading some of the nation's foremost research on stroke care.

Doctors at the center have long said that one of its more pioneering stroke treatments - fishing out a blood clot that has lodged in one of the brain's blood vessels - leads to massive improvements for people who suffer the most severe strokes.

That includes Ray Tapani, 77, of Crossville, Tenn. Last September, Tapani had just finished cutting his neighbor's grass and was rinsing off the mower when he began to feel a stabbing pain in his right leg. He does not remember much after that.

It was not until hours later that he woke up at Erlanger and his wife, Sandra, explained what had happened: The neighbor had called 911, and Ray had been helicoptered from Cumberland County to Erlanger. Scans showed a major artery had been blocked in the left side of his brain, and doctors quickly worked to insert a catheter through an artery near the groin, then thread it up to the clot in his brain, where they plucked out the clot.

"He probably would have been in a nursing home the rest of his life if he had not had this procedure," Sandra Tapani said. "But he came in on a Wednesday afternoon, and we went home on a Saturday. He was telling me how to drive home. We are truly blessed."

Ray later looked up pictures of the procedure and was in awe. Besides a little temporary short-term memory loss, he said he feels no lingering symptoms. He walks two miles on a treadmill every day,

"I tell you - if people could get the treatment I got they would be so fortunate," Ray Tapani said.

Now, a recent series of landmark medical trials, including one that involved Erlanger, could make that a more widespread reality - with findings that could have major implications for how hospitals worldwide approach stroke.

Stroke is the fifth-leading cause of death in the U.S. and often leaves survivors with crippling disabilities. Strokes are the top reason for nursing home admissions each year.

Doctors interviewed in The New York Times used phrases like "game changer" and "sea change" to describe the results revealed in one recent stroke trial that tested the same technique. Dr. Tom Devlin, chairman of neurology at Erlanger Health System, calls it the "beginning of a new era" - an era that Erlanger is helping to launch, he says.

"The bar is being set here," Devlin said.

Erlanger's stroke center, which treats about 2,200 patients annually, is already regarded as one of the nation's best. President George W. Bush toured the center in 2007.

But the doctors say the new research and other trials the hospital is conducting - including a new post-stroke therapy that involves stem cells - solidify Erlanger's place as a forerunner in the field.

The center hopes to build on this identity. Plans are under way to create a new neuroscience center at Erlanger's downtown campus. The hospital was just issued $71 million in new bond money to put toward capital projects, including building the new center in coming years.

Devlin envisions such a center as a destination for the research and treatment of strokes, along with other neurological conditions. And as the team of doctors there helps design new treatment devices and therapies, they say such activity brings new hope for people in the region who thought such strides were out of reach, or who traveled the globe looking for the latest advancements.

"This is like having NASA in our backyard," Devlin said.

A LONG FIGHT

The search for effective stroke treatments has been a long, uphill battle. But in each phase of the fight, the biggest obstacle has been the same: Time.

From the moment a clot lodges itself into a vessel and interrupts blood flow to the brain, every second brings a new wave of devastation. Two million brain cells die each minute the brain goes without blood. But most patients and family members don't realize that a stroke is happening until it is well under way.

Long-term effects of stroke vary based on what part of the brain is deprived of blood. The range can include everything from paralysis, seizures, the inability to talk or write, and behavioral struggles like depression.

The only FDA-approved treatment in stroke care arrived in 1995 in the form of the protein-based drug called tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA. The drug, streamed into the veins through an IV, helps dissolve the clot, like "Drano for your brain," Devlin described.

But while the drug has long been considered the "gold standard" for stroke care, it has serious limitations for many patients, the doctors at Erlanger say.

It is only effective within a crucial four-and-a-half-hour window - time that has often elapsed by the time most stroke patients get to a hospital, the doctors say. And for the most severe strokes, where clots are stuck in the brain's larger blood vessels, tPA simply does not work, no matter how quick the response.

Such large-vessel strokes make up about a third to a half of all strokes, the New York Times reports, and Tapani's was one of them.

So doctors began looking for ways to tackle such clots head-on. The late 1990s brought new micro-catheter technology, which allowed surgeons to thread tiny tubes through an artery near the groin up into the brain's blood vessels to stab the clot directly with tPA. Interventional radiologist Dr. Blaise Baxter brought the new techniques with him when he came to Erlanger in 1999, and helped develop the hospital's program.

A few years later, the technology advanced one step further - grabbing onto the clot in the vessel and pulling it out. The "clot grabbers" first looked a lot like corkscrews. They were tricky to use, Devlin said, like catching a "30-pound catfish on 3-pound test line." If the device snapped off inside a patient's brain, the resultant bleeding could cause death.

Later, clot-grabbers evolved into a vacuum-like device that sucked the clot out. Then came the model now known as a "stentreiver." That tiny device features a stent at the top, which expands into a tiny wire cage. When the catheter reaches the clot, the cage is opened and crushes through the clot "like a cheese cutter," says Baxter. The stent tangles with the clot, breaks it up and latches onto it as Baxter or other radiologists reel it in, while watching the X-ray screen.

The new device cut the amount of time needed for the procedure by half. The effects of blood flowing back into the brain are immediate. Some patients may begin talking again after 90 minutes, never knowing anything was wrong.

"They have no idea what they have just been through," said neurologist Dr. Biggya Sapkota.

And the ability to actually go into the vessel to remove clots widened the window of time patients could be saved beyond the 4.5 hours required for tPA. And while the old devices could remove only about 50 percent of clots, the new ones have removed 95 percent, Devlin said.

As the clot-grabbing technology evolved, the field blossomed. But while the devices are FDA-approved, the procedures themselves have never been considered standard stroke treatment - chiefly because there were no studies that showed they worked better than tPA.

And learning the new devices came with risks - puncturing an artery, or accidentally breaking up the clot before it could be fully removed. In the Chattanooga area, only Erlanger moved forward with "interventional" treatment, as it is called.

A major setback to the field came in 2013, when three trials ended without proving that the patients who underwent the clot-grabbing procedures benefited any more than patients who just had tPA. After those trials, Baxter said, all of the doctors who knew that interventional treatment worked "got organized, really quickly."

So when the opportunity arrived for Erlanger to join a new international, Canadian-based trial that would evaluate the interventional techniques they had been using, they signed up. Erlanger was the only American hospital involved, and Sapkota and Baxter became co-principal investigators for the study.

Both were convinced that the earlier trials had not passed muster for two simple reasons: Doctors had not used the most up-to-date tools, and they had not selected the appropriate patients. Patients could not be selected for the interventional treatment based only on their symptoms. They had to be picked on the condition of their brain, Sapkota explained.

Erlanger pharmacy technician Susan Rakestraw and pharmacist Dennis Buckelew remove a tray of "neuronlike" stem cells out of a -180 degree canister on Dec. 30, 2014. Erlanger is participating in the Athersys Study clinical trial. which involves injecting neuronlike stem cells into the body following a stroke to reduce inflammation, improve electroconnectivity and help grow blood vessels in the damaged area of the brain.

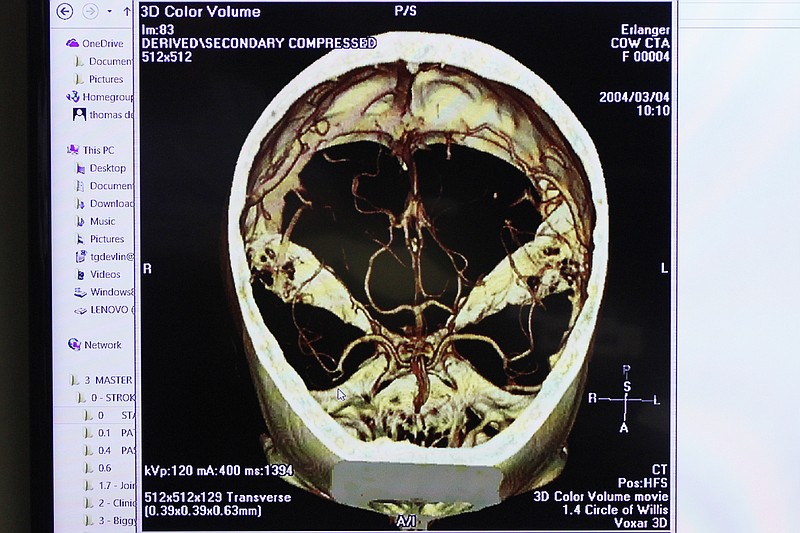

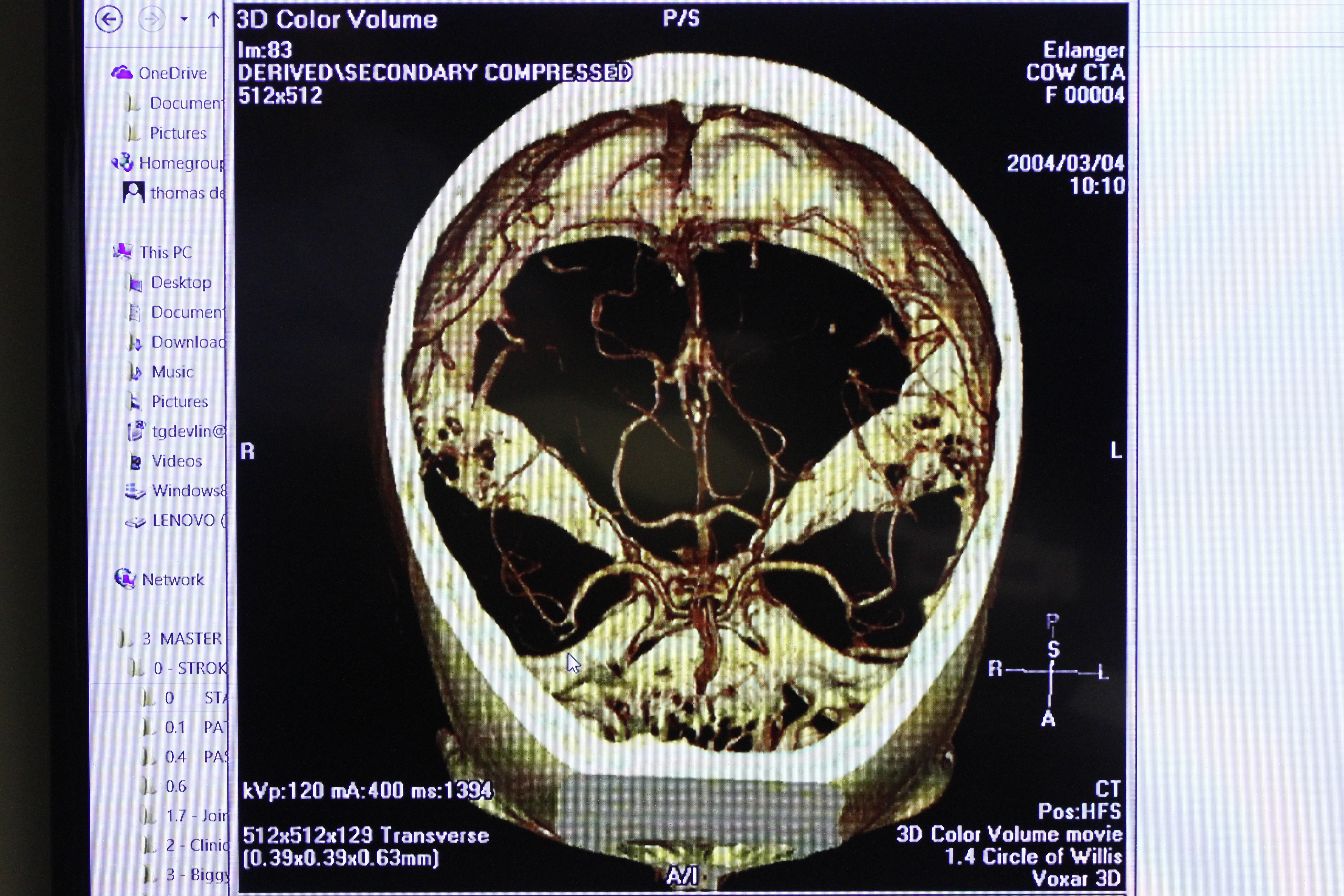

Erlanger pharmacy technician Susan Rakestraw and pharmacist Dennis Buckelew remove a tray of "neuronlike" stem cells out of a -180 degree canister on Dec. 30, 2014. Erlanger is participating in the Athersys Study clinical trial. which involves injecting neuronlike stem cells into the body following a stroke to reduce inflammation, improve electroconnectivity and help grow blood vessels in the damaged area of the brain. More sophisticated 3D scanning technology can allow neurologists like Sapkota to quickly evaluate whether the patient had a large-vessel clot, pinpoint where it was, and see how much of the brain had been affected from a lack of oxygen.

"The scans show just how much irreversible brain damage has occurred, and how much is still fixable," Sapkota said.

For the trial, Sapkota and his team selected only patients whose brain scans showed they had enough undamaged brain for the procedure to work. And once they screened the patients, the interventional radiologists like Baxter would use the most-up-to-date stentreivers to remove the clots.

But it's not just about the technology. It's about the process used, doctors say. Erlanger has a "well-oiled" operation for treating stroke patients, said Sapkota, which starts with helping to train EMTs and paramedics to recognize symptoms before patients are even delivered to the hospital, and which includes having a stroke team on staff at the hospital 24/7.

Having gotten the protocol down pat, Sapkota said doctors are now able to get patients from the door to scanners within 10 minutes. Their average time from the scanners to getting the clot out is less than 90 minutes. They've gotten clots out as fast as 42 minutes.

Such clockwork procedures, coupled with the large volume of stroke patients in the 5,500-mile region the hospital draws from, meant that Erlanger contributed more patients to the trial than any of the other medical centers included across the globe. The trial lasted less than two years, and was stopped early because the results were so positive.

"We get so many patients and we treat them fast, which is significant in making this trial positive," said Devlin.

The study will not be published until next month. But results from a similar study in the Netherlands, published in December in The New England Journal of Medicine, are already turning heads. That study found that while one in five patients who had tPA alone recovered enough to live independently again, one in three who had the clot removed directly showed that improvement.

"It's a big difference," Baxter said.

STEM CELLS

Even with all the new tools at the clinic's disposal, many stroke victims don't fully recover.

A stroke triggers a series of biological processes, Devlin said, that continue to damage the brain days and weeks and months later.

"We still have a long way to go," Devlin said. "Even if we get the clot out of people's brains, only about 55 percent of people have a good outcome."

That's where the stem cell treatment comes in. The theory is that the neuron-like stem cells will circulate in the patient's blood and secrete cytokines, proteins that serve as messengers between cells. The cytokines should reduce inflammation in stroke victims' brains, make new connections between surviving brain cells and help grow new blood vessels right in the area of the stroke.

For almost three years now, stroke victims at Erlanger's clinic who meet certain criteria can have stem cell treatment through a study funded by Athersys Inc., of Cleveland, Ohio. The stem cells come from the bone marrow of healthy donors and they're transformed in a New Jersey laboratory into cells similar to brain neurons.

Patients taking part in the trial at Erlanger receive a dose of up to 1.2 billion stem cells, which comes in a single bag and looks like a bag of brownish-colored blood plasma. Six people have chosen to have the stem cells injected at Erlanger - which doesn't cost them anything, since Athersys pays for it.

"It's like 'why not?'" said Katrina Barton, the certified clinical research coordinator who helps Devlin oversee the study. "We've seen some results that have been very impressive. The thing that's impressed me the most is the improvement at day 30."

Still, neither Devlin nor Barton knows whether the stem cells made a difference, because they're overseeing a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. That means each patient has a 50-50 chance of getting a placebo or stem cells, and neither they nor Devlin knows which.

Administering the cells is no simple task. They are frozen in liquid nitrogen, come packed in dry ice and go into storage at Erlanger in a liquid nitrogen cooler inside the "nitro room" deep inside the hospital's pharmacy that Athersys installed at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Two hospital pharmacy employees have to team up to thaw the dosage under running water, mix it, and fill out some 28 pages of paperwork. Then, laboratory techs must examine a sample of each dose of stem cells under a microscope to ensure they're viable.

The amount of scrutiny the FDA has over the research is "unbelievable," Devlin said.

Medical history is littered with examples of treatments thought to be beneficial that later were found to be harmful, Devlin said. Instead of taking a hit-or-miss approach in which stem cells are injected to see what happens - as stem cell clinics abroad have been faulted for doing - FDA-approved studies take a more cautious approach.

IMPLICATIONS

Erlanger will get to see the final results of the trial when it is presented at the International Stroke Conference in Nashville in February. There are many possible implications from the positive trials, the Erlanger doctors say. But the key one is that "there will be no more question as to whether intervention works," said Devlin.

Such agreement in the medical field, he said, will mean that the techniques doctors at Erlanger have been using for years will become a technically FDA-approved treatment, and the agency may start relabeling devices specifically for stroke.

Such a "tsunami of evidence" would also mean insurance companies would have a more defined protocol to pay for such procedures.

Currently, insurers like BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee consider the mechanical clot-removal procedure to be investigational.

"With all our policies, we determine medical necessity based on the available scientific evidence - which this study will add to - and we engage in a formal review process," said BlueCross spokeswoman Mary Danielson.

If that happens, it could mean destination guidelines - which direct patients to different hospitals based on their particular symptoms - could change, positioning Erlanger to see a greater influx of stroke patients.

"This is huge because if it works, it becomes standard of care for patients across the country," said Baxter. "Erlanger will become a model for the standard of care."

Contact staff writer Kate Belz at kbelz@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673. Contact Tim Omarzu at tomarzu@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6651.