Katrina Gilbert teeters between two worlds.

In one, she flies to Los Angeles first class, stays at the Four Seasons and attends the Emmy Awards. In the other, she pays for her groceries with food stamps, worries about how to get rid of the mold in her kids' bedrooms and is buried under medical bills.

A lot has changed for Gilbert since she appeared in the HBO documentary, "Paycheck to Paycheck: the Life and Times of Katrina Gilbert," which debuted in March 2014.

But a lot has remained constant.

Through Gilbert, the film told the story of the 18 million adult American women living in poverty.

In the film, Gilbert, a mother of three young children, struggles to pay for medical tests, groceries and other household needs while earning $9.49 per hour as a certified nursing assistant.

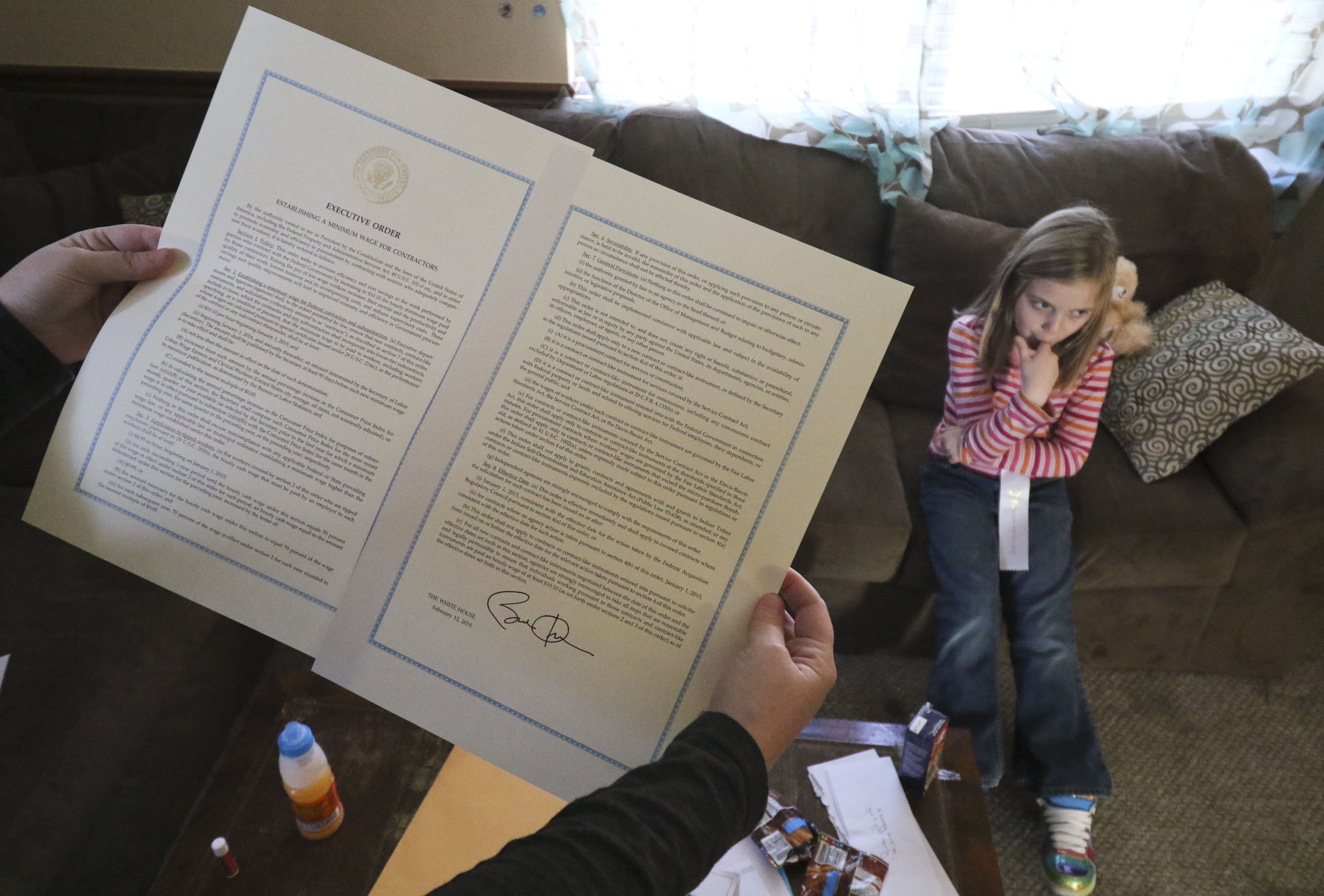

Her time in the limelight helped her become a frequent guest speaker for corporations and nonprofits, earning some income as she flies across the country. She stood by the president in the Oval Office as he signed an executive order raising the minimum wage for federal contractors.

This November, she'll marry her fiance, Chris, in Coolidge Park. And she just completed her first full-time semester at Chattanooga State Community College.

The film, released on HBO and on DVD, prompted donations of cash, furniture and child-care costs for Gilbert. And it made her a face in the national fight against poverty.

"I sometimes wonder, 'Why me?'" she said. "I'm just a girl from Chickamauga, Georgia, who graduated from Ridgeland High School. I was this nobody. And for some reason I was chosen for this. I was chosen to be the face of poverty, the face of millions of others living in poverty."

Across the country and around town, people approach Gilbert and tell their stories. How they're trying to make ends meet with two jobs. How they've got an old, no-good car. How they can't afford child care.

She tells them to hang on, that things will get better. Every storm ends eventually.

Her travels have allowed her to see poverty beyond just her own circumstances and have transformed her into an advocate for the working poor.

"Hearing their stories, it's shocking. It's amazing," she said. "I can't believe that there's that many people in America that are living like this. And we're supposed to be the best place in the world."

The documentary was produced by Maria Shriver and was preceded by the release of The Shriver Report, a massive study that found that about one-third of American women -- 42 million -- live in or on the brink of poverty.

"As tough and inspiring as Katrina is, there are lots of people out there trying just as hard," said Joan Entmacher, vice president for family economic security at the National Women's Law Center, which advocates policies that expand the possibilities for women. "But it's really, really tough."

It's even tougher in Tennessee and Georgia, where adult female poverty rates run higher than national averages. Nationally, the poverty rate among single mothers is 39.6 percent. It's 53.8 percent in Georgia and 47.9 percent in Tennessee.

And state policies aren't helping, Entmacher said.

Georgia and Tennessee are not among the 29 states to pass legislation boosting the minimum wage above the federal rate of $7.25 per hour. A report released last week by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that Tennessee's tax rates are among the top 10 most regressive in the nation, meaning the poor pay a greater share of their income to taxes than the wealthy do.

And there's not much of a safety net. In Tennessee, the maximum welfare benefit for a family of three is $185 per month, Entmacher said.

"That's why people are out there killing themselves, in some cases literally, trying to get by in these low-wage jobs," she said, "because we don't have a safety net for them anymore."

The documentary showcased the work of the Chambliss Center for Children, which provides affordable, round-the-clock child care for the working poor. Gilbert has relied on the center's services and they've helped her deal with the influx of donations from viewers.

One woman sends $75 a month that goes to pay down Gilbert's medical bills. Another person offered to buy Christmas gifts for her kids.

Katie Harbison, vice president of development and administration at the Chambliss Center, said the experience has been good for Gilbert. But it hasn't fundamentally changed her.

"I think for the most part she's still living the same life. She still struggles to pay bills. She still lives in that horrible house that floods when it rains," Harbison said. "While the documentary did help her in some small ways financially, it didn't bring her out of poverty completely."

The film has given Gilbert a taste of life beyond poverty. On her trips, she gets a little pampering. She stays in nice hotels and goes out for nice dinners. She doesn't live in that world, Harbison said, but she has renewed hope that she and her family could make it there some day.

Some donors from out of-state started giving to the Chambliss Center after the film aired, Harbison said. But more important, the documentary prompted a national discussion.

"The point wasn't, 'let's help this poor mom Katrina,'" she said. "The point was what can we do as a country, as a society, to help the millions of moms who are struggling to take care of their children. I think it really is more about a broader point."

And Gilbert herself is now focused on the broader issue. She's working part-time (now earning $9.82 per hour), but focusing much of her energy on school. She hopes to get a degree in media technology and wants to continue advocating for the working poor. She knows the donations and the fame will dry up soon. People will turn their attention elsewhere.

For now, she's working on being self-sufficient.

"I'm trying to make a difference, not just for myself but for everybody," she said. "I'm pushing."

Contact staff writer Kevin Hardy at khardy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6249.

News report from the release: