Eric Westmoreland heard from fans occasionally when he roamed the University of Tennessee campus as a standout linebacker from 1997-2000.

"After the games, walking back to the dorm rooms, seeing people on campus or going to the grocery store," the Marion County native said. "Stuff like that."

UT supporters had little to complain about during Westmoreland's career - the Vols were 41-9 and won the 1998 national championship. But in that era, even if a sports fan became frustrated with a player's performance, their platform for expressing displeasure was limited.

Now, in the social-media age, masses of fans in a moment of frustration can tweet their rage directly at 18- to 23-year-old student-athletes, an age group experts say are likely to process the negative attention differently than would older, professional athletes.

"When the players and coaches have Facebook and Twitter pages, they see those comments," said Westmoreland, an assistant coach at Baylor School who coached UT linebacker Colton Jumper for four seasons.

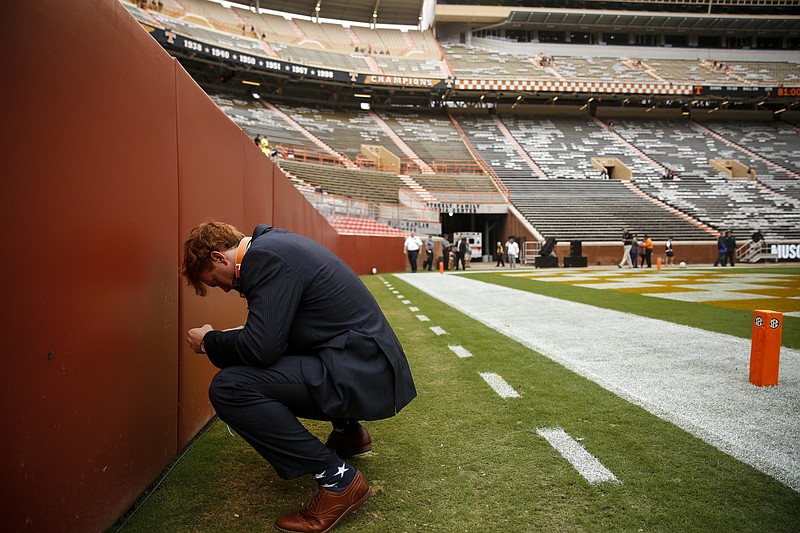

Jumper, a sophomore walk-on for the Vols from Lookout Mountain, became a target for UT fans on social media during the team's early season losses to Oklahoma and Florida. Some tweeted criticism and insults directly at his Twitter account, @jumper_53, while others ripped him without actually tagging him directly. Those tweets could, and still can, be found by searching his name.

Jumper is far from the only college athlete to experience social media harassment, but he is a local example of a nationwide phenomenon that is especially prominent in the Southeastern Conference, where college football allegiances run deep.

Alabama fans tweeted profanity-riddled death threats to former Crimson Tide kicker Cade Foster after he missed three field goals in a 2013 loss to rival Auburn that dashed Alabama's national championship aspirations. Some fans defended Foster - as some have defended Jumper - but the situation showcased social media's unflattering side.

Thirteen of 37 SEC players who responded to a CBS Sports survey question reported that they receive social media harassment "very often," and nine said they were at least occasionally harassed.

Social media researchers say college programs must educate players on how to deal with the floods of vitriol.

"Colleges, they've increased social media training, which is great," said Blair Browning, an associate professor at Baylor University who has done extensive research on social media in sports. "But I think there's still a gap, because it's still training on how to use social media, and not how to process the comments that come into them, especially in the Power Five conferences where everything they do is under a microscope."

Tennessee and Georgia did not respond to inquiries about how they train players to handle fan negativity on social media.

A source in the athletic department at Alabama said players are told not to engage with argumentative or derogatory fans.

"But I don't think anyone can sit here and say they're not going to see it," the source said. "Because they are."

Tweets trashing Jumper started appearing during UT's Sept. 5 game season against Bowling Green, when he was tasked with covering one of the opposition's most agile receivers.

The tweets picked up the next week in both frequency and vulgarity during UT's loss to Oklahoma, when Jumper committed a pair of holding penalties.

"Colton Jumper is a B****," tweeted one Twitter user, @sengland676. "Get his a** out of there."

"Colton Jumper is a**," tweeted @Matt_Oakes5.

A few fans, like @shawtygot_LOWE, who is wearing a UT jersey and posing with a UT player in his Twitter picture, tweeted directly at Jumper.

"@jumper_53 you shouldn't be allowed to live in Knoxville," he wrote.

Jumper did not respond to the critics - players rarely do - although his mother, Dawn, felt compelled to reply to some.

A UT athletic department spokesperson said Jumper would not be made available to be interviewed for this story.

Dr. Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center in Newport Beach, Calif., said fans see their favorite teams as an extension of themselves, a part of their identity.

"That player not doing well, they feel, is diminishing them or diminishing what they stand for or what's important to them," Rutledge said. "It's not about the player it's really about the person making that comment - not about the recipient."

Then there's the fan's perspective.

Blake Bibat, a recent UT graduate who has been a vocal critic of Jumper on Twitter, said he sees no difference between tweeting about a bad lunch at a restaurant and tweeting about a player's performance.

"Twitter is a venue where anyone can offer their opinion on anything," Bibat said. "From actors, restaurant servers, co-workers, to football players. The opinions are out there, and it's up to the individual if they want to know what people think. Colton has the option to know what people think, and that's his choice, but my opinion will still be out there."

Coaches generally tell their players to tune out external distractions. Players, when asked, often say social media does not affect them, but ignoring the naysayers is easier said than done, Browning said. Responses to the CBS Sports survey indicated the same.

"God forbid you give up a sack and have a bad game and you're going to hear about it," Georgia offensive lineman John Theus told CBS Sports. "You just have to learn how to ignore it and shut it down. That's a rule of mine [not to engage with fans]. If I see a teammate doing that, I try to say it ain't worth it."

Westmoreland said if social media had been around during his playing days, he's sure some of the team's close losses would have prompted fans to lash out.

"Time heals all," Westmoreland said. "People get back to their normal lives after a day or so."

But in today's world, impulsive reactions are preserved on the Internet even after the frustration subsides.

"Everyone has an opinion," Browning said. "The thing is, now they have a platform. I don't think that's going to change."

Contact staff writer David Cobb at dcobb@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6249. Follow him on Twitter @DavidWCobb