On Friday morning, Aug. 12, when she is standing at the starting line for the 10,000 meters race in Rio de Janeiro, Canadian distance runner Lanni Marchant won't be thinking about the Zika virus. Nor will she be worried about the drinking water in Rio. Any concerns about terrorist attacks will be gone, as will thoughts about crime in the streets of the Brazilian city.

She won't be thinking of her apartment in Chattanooga, or the cases she is researching for her law firm there, Speek, Webb, Turner & Newkirk, where she is a criminal defense attorney.

"I don't try to ignore what's going on in the world around me," said Marchant, who has a B.A. in economics from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, as well as a law degree from Michigan State. "It's very much having tunnel vision, to focus on what I'm doing. I can only be as prepared as I can be to run as fast as I can and race well - that's in my control."

For months now, reporters have been writing stories about everything wrong with Rio: how the Zika virus can cause deformities in babies, how terrorists can't resist a gathering where the whole world will be watching, how Rio is just not ready - raw sewage is still spilling into the bay, police officers are threatening to strike, there hasn't been time to test a new subway line.

But if interviews with athletes and doctors with ties to Tennessee are any indication, all of that is just so much background noise when the moment comes for which they have trained for years.

"There is a lot of talk about Zika and safety issues and all of that stuff going round, but it is really not much of an issue for me," said Michal Smolen, who learned to kayak at the Nantahala Racing Club northwest of Chattanooga and will compete in the kayak slalom. "For me it's just the race itself, because I have been waiting for an opportunity for a really, really long time."

Smolen is fortunate - the kayak slalom course in Rio is artificial, so the water is chlorinated.

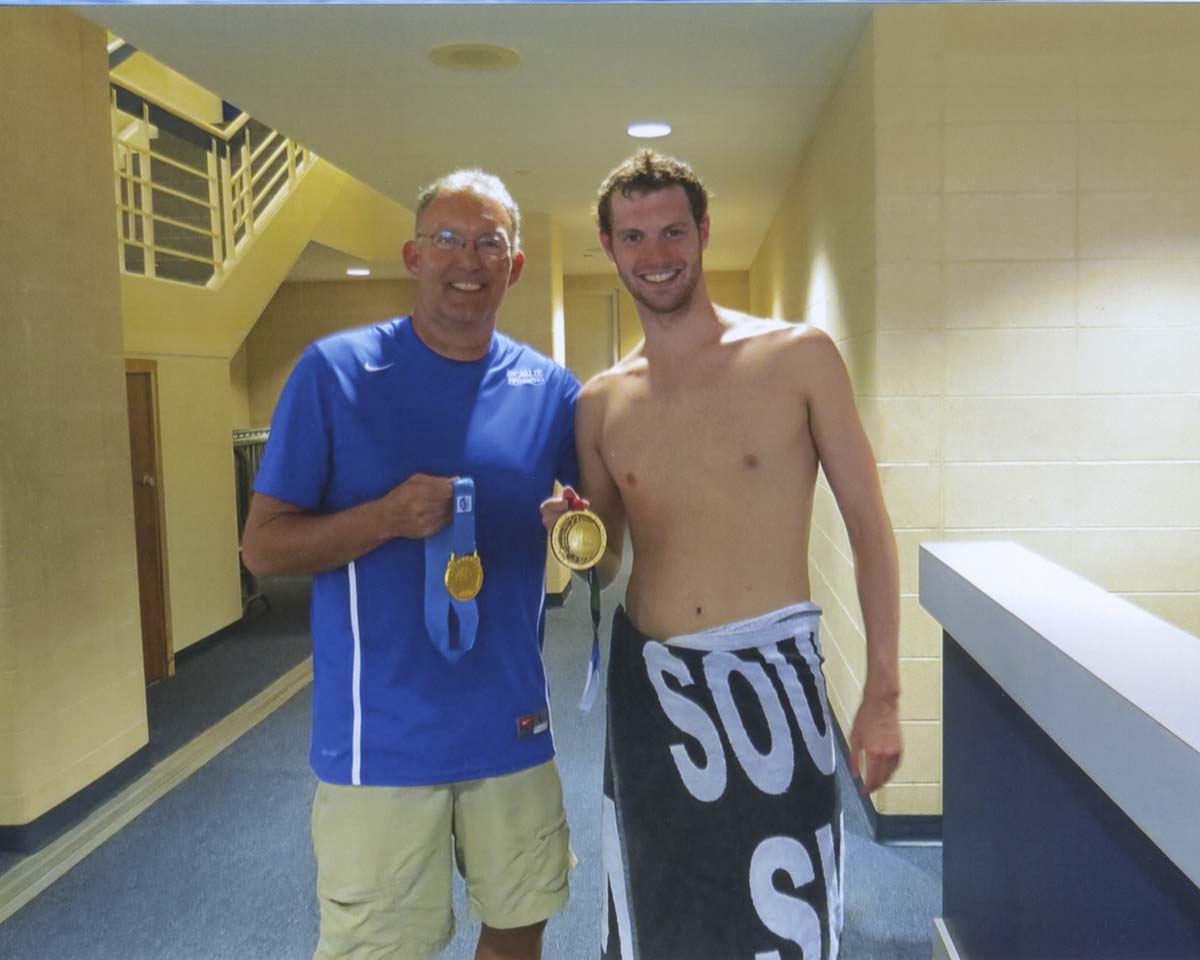

Chattanooga native and former McCallie swimmer Sean Ryan is not so lucky. His event is the 10-kilometer (6.2-mile) swim in the open ocean off Copacabana Beach.

Before the Olympic committee awarded the 2016 games to Rio, local officials promised that the amount of raw sewage now dumped into the ocean off Rio would be reduced by 80 percent, but even Brazilian officials admit that progress has been much less. Brazilian researchers recently identified the presence of a drug-resistant "super bug" bacteria in the water near where Ryan will swim for two hours, but he said he is not worried.

"As long as nothing drastic happens, I'm just going to worry about my preparation and being in the best condition I can be," Ryan told the Times Free Press in a recent interview.

Ryan also has his own medical advisor - his dad is Dr. Eugene Ryan, an internal medicine specialist with Parkridge Medical Group in Chattanooga. Ryan, who will be in Rio with about a dozen family members and friends, pointed out that Sean regularly swims in water that is not as clean as that in the McCallie pool.

His son has swum in the Mediterranean off of Ostia, the ancient Roman port city; and off the coasts of Abu Dhabi, Shanghai, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Long Beach, Calif.

In Rio, "All the sewage is concentrated in the bay," Ryan said, although he noted that in the ocean Sean also will have to be on the lookout for plastic trash, sharks, and jellyfish. In several other similar races in the same area, no one has gotten sick, he said.

While his son would like to get in a practice swim in the water where the competition will take place, he might skip that if the pollution is particularly bad. It takes six to eight hours to get sick, so if a swimmer does a practice run two days before the race and becomes ill, they are out of the competition. But if they don't get in the water until race time, and the race lasts two hours, "They may get sick after the race, but they finish the race," Ryan said.

The health risks for Sean Ryan are real.

"I don't know if it is a super-high risk, but it is certainly a risk," said Dr. Mark Anderson, an infectious disease specialist with CHI Memorial Hospital. "As far as prevention, I don't know if there is really much you can do except hope that you are swimming in an area that is not close to the direct dumping."

But Anderson noted that all of the athletes will have had vaccinations and are in extremely good health.

Many of the health concerns are the same for anyone traveling in a foreign country.

"Rio is a mountainous beach town, and it is very, very congested. Public services aren't as great as in most big cities here," said Dr. Bill Moore Smith, head doctor for the UTC sports teams who has worked with Olympic teams from the U.S. and Germany for many years. "A lot of it is being in a different country, sleeping in a different bed, eating different food."

The risk from the mosquito-borne Zika virus is still there, but it has decreased, according to Anderson. August in Brazil is a dry month, not peak mosquito season, he said.

"Wear the best lotion that has DEET in it, that stays on when you are sweating, and hope that with the seasons it will be less of a risk," Anderson said.

"I go to Kenya every year to train and there are health concerns there," said Marchant, who will compete in both the 10,000 meter and women's marathon. "I will do what I can to avoid mosquito bites - who would want them anyway? I don't mean to downplay the threat, but it is not something I can put into my mind and worry about."

Marchant has one advantage - she can move faster than almost anyone else in the world.

"Someone running that fast, they're less likely to get mosquitoes," Anderson said. "They tend to get you when you are stationary, so the spectators are more at risk."

And the athletes have another advantage as well.

"For the teams, they travel with such a strong contingency of health care people - doctors and trainers and para-medical type people," Smith said. "The U.S. delegation will be better taken care of than anybody in the world."

Contact staff writer Steve Johnson at 423-757-6673, sjohnson@timesfreepress.com, on Twitter @stevejohnsonTFP, or on Facebook, www.facebook.com/noogahealth.