Moments after the first shots rang out, a teenager dashed out of the house party and ran into the street, firing a shotgun from his hip as the shooter's car sped away.

Five people were injured in that shootout at 2412 E. 13th St. on the last day of November in 2014.

Three days later, city code inspectors paid a visit to the home. The house was dangerous and unfit for habitation, they declared, saying it violated general cleanliness standards and failed to meet minimum electrical and heating requirements.

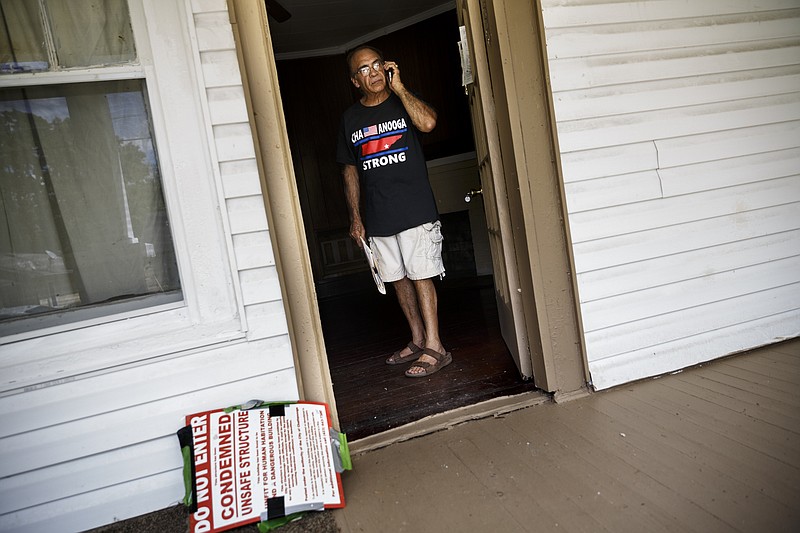

The house was condemned; the woman who said she lived there was evicted until the landlord made repairs.

It's a process the police tout as classic community policing - a way to solve a problem and rid a neighborhood of a troublesome house or tenant without necessarily slapping someone in cuffs.

For about two years, Police Chief Fred Fletcher has pushed officers to increase cooperation with the city's code inspectors. In mid-2014, two of the city's 12 code inspectors moved into the police department to foster that relationship. Since then, police have worked with code inspectors to close brothels and gang houses.

But while many residents praise the partnership, some landlords are pushing back, claiming the approach unfairly concentrates inspections on properties in high-crime, low-income areas and creates an unnecessarily adversarial relationship between landlords and police and inspectors.

Since the police department ramped up efforts with code enforcement, the number of homes condemned in Chattanooga has steadily risen, from 117 in 2013, to 200 in 2014 and 238 in 2015. So far this year, at least 117 homes have been condemned as of July 8, city records show.

And of the homes condemned in 2015 and 2016 that haven't yet been repaired, nearly half - 45 percent - were condemned by the two code inspectors who are housed in the police department, records show.

Some landlords believe those two inspectors prefer to jump right to condemnations, where tenants must be out within 24 hours, without giving landlords a chance to make repairs.

"Obviously, if you look at a house and the structure is bad, that should be condemned," said landlord Mick Frazier. "When there's nothing wrong with a house other than crime, or you got a broken window or an open door, what happened to the days when you call the landlord and say, 'Hey, your door is open.' And then it's, 'OK. I'll be right down.'"

Fletcher and city officials assert that the code enforcement process is fair and houses are only condemned if they fail to meet the minimum safety requirements set out in city code. Those requirements range from having handrails on porches to having structurally sound floors and running water. Code enforcement is an important tool to help communities get rid of criminal activity and blight, Fletcher said.

"Neighbors are calling to complain, saying people are shooting guns, selling drugs and causing disorder in our neighborhoods," Fletcher said. "We're going out there, and we're finding these are houses that nobody should be living in. They don't have plumbing, they don't have electricity. It's not like we're condemning them because their insulation is one degree off of code. These are houses that human beings shouldn't be living in, and that's why they're getting shut down."

***

Most of the work code inspectors do is driven by complaints, said Donna Casteel, chief code enforcement inspector for the city.

Often those complaints are reported to the city's 311 service center by citizens, but firefighters, police officers and public works employees also forward complaints to inspectors, Casteel said.

Inspectors are required to investigate a complaint within three business days. Some inspectors focus on litter complaints, others check out abandoned or disabled vehicles. Some deal with vegetation overgrowth or abatements. The two inspectors who work at the police department only handle housing violations, Casteel said, so she's not surprised they're responsible for nearly half of recent condemnations.

When it comes to housing, inspectors have two main options. If a house violates city code but the violations don't present an immediate danger to tenants, the inspector sends a list of problems to the owner and sets a time frame for the violations to be fixed.

But if a house is so far out of code that it presents an immediate danger to residents, inspectors can condemn the structure on the spot and give the residents 24 hours to move out. No one can live there until the repairs are made. After repairs are made, inspectors typically revisit the home within three business days and can allow people to move back in if it's up to code.

Inspectors work with nonprofit organizations and service providers to try to ensure evicted residents have access to emergency housing for at least the first night and sometimes longer, Casteel said.

She contested Frazier's claim that inspectors don't offer landlords the chance to make repairs before condemning a house.

"If there is something that is not an emergency but it does have to be fixed, like it's 30 degrees and there is no heat, it's not unusual for an inspector to call the owner and say, 'Hey, if you get the heat fixed today, we won't have to condemn this house,'" she said.

Whenever a code inspector condemns a house, the residents must be out within 24 hours. But not every house is condemned on the inspector's first visit, Casteel said. However, the city doesn't track at what point in the process houses are condemned - whether on the first visit or after landlords have been given a chance to make repairs.

Casteel emphasized that inspectors who discover dangerous violations have an obligation to condemn the home and get residents to safety.

"If they don't go ahead and condemn the house and displace the people, and the house burns down that night, the inspector was aware of it, so the city and the inspector both carry some liability where that is concerned," she said.

Most of the houses condemned in the last two years are in East Chattanooga, where the majority of homes are rental properties and many are in poor shape.

Landlords undoubtedly have a responsibility to keep their houses in livable condition, said Martina Guilfoil, president and CEO of Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise, a nonprofit focused on quality housing.

But sometimes, homes are in such poor condition that they cost more to repair than they're worth, and that can make it difficult for homeowners and even landlords to come out in the black.

"The economics makes it really tough in some of these neighborhoods to make it pencil out," she said. "I'm not saying that's the right way, I'm just saying these are the challenges we face on why a lot of these houses are substandard."

Much of Chattanooga's affordable housing is also in bad shape, but condemnations can create a new set of problems when tenants end up homeless, Guilfoil said.

"We fret about this often," she said. "Either you live in something that is uninhabitable by our standards, or you're homeless. So is it better to live in a dilapidated house than out on the street? Probably. But then again, where are the landlords?"

Gary Ball, a landlord in the Ridgedale neighborhood, routinely reports suspicious activity and dilapidated houses to police. He said the landlords complaining about the police-code partnership are also the ones making the most money renting out poor-quality homes without making basic repairs.

"It interrupts their money-making cycle, is what it does," he said.

But he also said condemnations don't seem to make much difference in a neighborhood in the long run. Usually, he said, landlords bring the property back up to code within a few months and rent the again - often bringing new trouble to the neighborhood.

"To me, it's not so much that codes and enforcement is picking on the same landlords over and over, it's that invariably, they end up renting to the same clientele; the neighbors who were complaining [earlier] are the same ones complaining about the same property this time," Ball said. "It's a merry-go-round that goes around and around and around."

***

Ron Bhalla, a landlord who owns about 30 low-income rental properties across the city, has a laundry list of complaints about code inspectors and police.

He wants inspectors to give landlords notice before condemning properties, and he thinks inspectors require changes on cosmetic issues, like peeling paint, instead of structural issues. He argues that code inspectors shouldn't be called because of a criminal complaint and said the increase in condemnations threatens to put him out of business.

"We are not in the business of cosmetics," he said. "We are in affordable housing. We deal with the low-end people, the low-end properties. If there is a safety hazard, that is what the inspector should cite. But they start saying, 'Oh the paint is peeling, the previous paint is another color.' This is a property we're renting for $500. We're not renting for $1,200. They have no consideration for that."

Casteel said inspectors don't care about the rent or the location of a home, and a complaint is a complaint, whether it comes from police or from citizens.

"It doesn't matter who initiates the case," she said. "We focus on the structure. That is all we care about."

Bhalla recently met a potential tenant at a home on Davenport Street that has been bouncing back and forth between being condemned and livable. In February, it was condemned because raw sewage was backing up under the home, there were no smoke detectors, the windows were boarded and there was evidence of mold inside, among other violations, according to city records.

Now that it's back up to code, Bhalla is hoping to rent the place again, perhaps to Haneefa Muhammad. She's been living in her truck, in hotels and with friends and family since May, when the home she was living in on Wilcox Boulevard was condemned.

She said she'd been living in the Wilcox house for several months when her son got into trouble and the police showed up. The police alerted code inspectors to the home's condition and Muhammad was told to move out within 24 hours.

She spent three weeks in a shelter, she said, but hasn't found a permanent place to live. She was frustrated by the condemnation process.

"My biggest concern is you're not giving anyone a chance to do anything either with the landlords or with the tenants," she said. "Faulty wiring is dangerous. Bad plumbing is dangerous. But you can give time - because a contractor can come in a house in a day or two and fix it."

On Thursday, the home on Wilcox was still condemned.

Fletcher said he wasn't familiar with the specifics of Muhammad's case, but he's confident the code inspectors only condemn homes that are unlivable. And he said the vast majority of homes police report to code inspectors are the ones where trouble happens in neighborhoods.

"Overwhelmingly these are shutting down houses that are causing fear and disorder in their communities, and [neighbors] are supportive of it," he said. "It's either up to standards or it's not. You either fix it or you don't. If these landlords don't want to spend the money to get it up to standards, then they can't make money renting it off to people in uninhabitable conditions."

Records show that police were called to Muhammad's home at least three times in the 10 days before she said the home was condemned - twice for a disorder with a weapon, and once for a miscellaneous complaint. Records also show that someone asked police to put the home on a "watch list" but don't say why the caller made the request.

Police were unable to provide the reports filed about the incidents before this story's deadline. The city was also unable to provide records detailing the inspections and condemnation of Muhammad's house before deadline.

Contact staff writer Shelly Bradbury at 423-75-6525 or sbradbury@timesfreepress.com with tips or story ideas. Follow @ShellyBradbury.