Most people have never heard of Isabel "Belle" Cobb, a Cherokee girl who lived with her family near Red Clay in Bradley County during the 1860s and 1870s

The little girl who would become the first doctor in Indian Territory made her way to a one-room schoolhouse by crossing Candies Creek and a ridge by the same name where homes, apartment complexes and shopping centers stand today.

Cobb was a good student, winning spelling bees and scholastic awards. That hunger for knowledge stayed with her when her family moved from the East Tennessee hills to Oklahoma, where she eventually became a medical doctor. Cobb cared for her people in a time when women often struggled to get any kind of education, much less attain a degree from a Pennsylvania medical school.

"It was when women in the rest of the country couldn't even vote yet," said Christine Johnson, one of the students who participated in a historical research project during fall semester at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The students were in UT professor Dr. Julia Reed's upper-level history course, titled "Not just Sequoyah and John Ross: Cherokee History through Biography."

Johnson, 36, is a Dayton, Ohio, native who calls herself a "nontraditional" student. She chose to research Cobb - who was born in 1858 in Morganton in Blount County and moved as a small child to Bradley County - as an educated woman who beat the odds and who makes an excellent role model.

"I wanted to make sure girls, especially young Cherokee girls, knew about this woman who was a doctor at a time when women were not doctors," Johnson said.

Her professor, Reed, a 39-year-old Cherokee historian and member of the Cherokee Nation, said the idea for the research came from a desire to tell the story of the Cherokee accurately, with a focus on lesser-known figures such as Cobb, Oce Hogshooter and Bluford Sixkiller.

Reed's course is tied to the Smart Communities Initiative, a service-learning partnership between UT and the Southeast Tennessee Development District, which represents 13 counties in the lower right corner of the state.

"A couple of years ago I was asked to fact-check a biography on the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation, Wilma Mankiller," Reed said. Mankiller was principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma from 1985 to 1995.

That book was aimed at children like Reed's then-8-year-old daughter, she said.

"As I was fact-checking I saw the kind of language that was being used to talk about Cherokee people and to talk about Wilma Mankiller, and [saw] that it kind of sets, for the rest of children's lives, their thinking about the Native Americans," she said.

Looking at one of her own ongoing projects, she realized many characters in Cherokee history who weren't as politically important were missing from more scholarly works. Combining those concepts, Reed decided those stories should be told to the youngest audiences so they have the proper foundation to learn more.

In the initial two classes in the fall of 2014, Reed generated a list of 40 names and asked students to choose one to research. She thought the biographies could be collected and published for children, like the book on Mankiller.

Distilling the information into a children's book of only 500 or so words or so would force students to concentrate on the most important parts of the Cherokee subjects' lives, Reed said.

Students read other child-focused biographies to see how other writers told stories about historic figures and to apply what they learned to their own work.

Johnson and fellow students Jacob Ottinger and Katie Myers - three of the five students in fall 2015 classes - had that task.

Johnson said of Cobb: "I was able to explore her diaries, I was able to explore her medical notes and medical records. It was just really, really interesting stuff.

"I was lucky enough to get some old rolls from when she was at the Cherokee Female Seminary. I wanted to keep going and I wanted to find out about her family and their time near Red Clay," Johnson said.

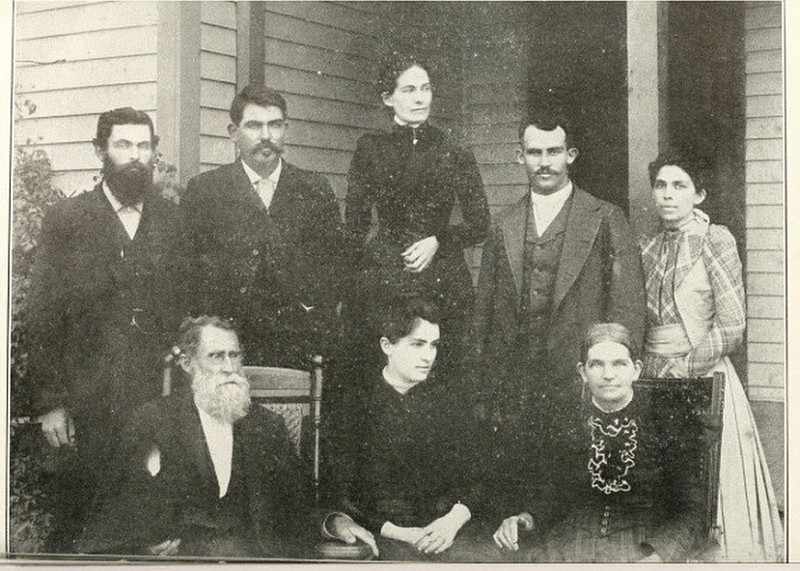

Cobb's mother's family, the Blythes, lived near Red Clay, the Cherokee Council grounds, as did much of her father's family, Johnson said. But she decided to focus on Cobb's successful medical career as an inspirational story for children.

The three students are excited Reed is collecting work from them and the fall 2014 class for publication. Reed said she plans to partner with members of the Cherokee Nation to translate the biographies into the Cherokee language and will contact Cherokee artists about illustrating the books.

Ottinger, 21, of Kingsport, said he began to realize what he'd created when he saw the information compiled in a digital document system that described the life of Redbird Smith, a Cherokee leader in Oklahoma born in 1850.

The semester-long project seemed like a hodge-podge, but when it finally came together, "it felt really amazing to see these scraps of information that, held by themselves, don't make sense, but put together, tell a story that hasn't been told," Ottinger said.

He was impressed by Smith, who died in 1918, because he focused on family and traditions, Ottinger said. Smith "was a community leader by a very young age. He was first a sheriff for the Cherokee Nation living in Oklahoma at the time, and then he became a council member for the Cherokee Nation."

Myers researched Polly Mocking Crow, a woman who lived in what is now Polk County, Tenn.

"For someone who grew up in the Internet age, finding things in books is embarrassingly difficult," Myers said. "I had to research her circumstances and area more than her name. I found that was a better way to tell her story, through all the things that existed around her."

Mocking Crow left Tennessee during the Cherokee Removal with the Hildebrand detachment, leaving behind a half-acre of vegetables growing on property she owned, Myers learned.

That was typical of Cherokee life for that period, since women were responsible for a lot of the agriculture. Mocking Crow would eventually ask for repayment for her featherbed and other goods, which was an indication she may have been a woman of means.

"This has been important to me, to research someone who was not a chief or any important person but a really normal person and a woman - a housewife with children," Myers said. "This story is so seldom told and I wanted to tell that story."

Reed said children remember stories.

"Dates and facts - there's a belief that that is what history is," she said.

"But what are they going to remember 15 years after they take these classes?" Reed said. "They might be able to tell me a story about his person's life. That would be an accomplishment for them and for me."

Contact staff writer Ben Benton at bbenton@timesfreepress.com or twitter.com/BenBenton or www.facebook.com/ben.benton1 or 423-757-6569.