Chattanooga prosecutors won't use the word "terrorist" when they resume a federal case today against a 65-year-old Tennessee man charged with planning to attack a Muslim community in New York.

Robert Doggart recruited people from right-wing social media sites, openly discussed using assault rifles on Muslims, and wanted to use explosives to burn down a mosque at Islamberg near Hancock, N.Y., prosecutors told jurors in Chattanooga's U.S. District Court last week.

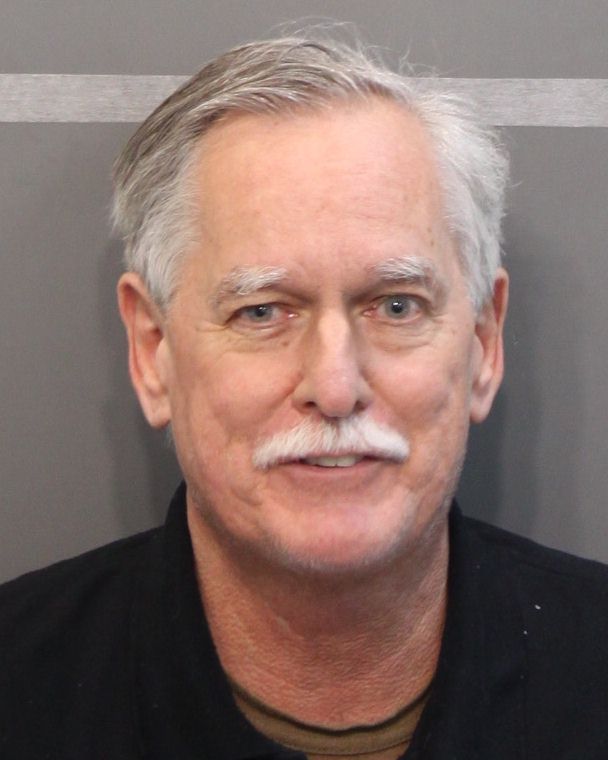

Doggart, a former engineer at the Tennessee Valley Authority and a 2014 congressional candidate, never launched his planned attack because authorities stepped in and arrested him on April 10, 2015, prosecutors say. He faces one count of solicitation to commit arson of a building, one count of solicitation to commit a civil rights violation, and two counts of threat in interstate commerce, records show.

But he wasn't charged with terrorism, say attorneys for Islamberg, because the federal government doesn't have a powerful, catch-all statute to punish alleged domestic terrorists like Doggart or Dylann Roof, the white supremacist convicted of killing nine black churchgoers in South Carolina in 2015.

"Any time you see Muslims charged with terrorism, [prosecutors] often have this link to 'they were looking up ISIS- sympathizing websites' because then they can get them on an international terrorism charge," attorney Tahirah Amatul-Wadud said Friday. "Essentially, your charge is connected to something overseas."

Acts of domestic terrorism must attempt to coerce people, intimidate government through mass destruction, and occur within the jurisdiction of the United States. Since Sept. 11, 2001, white supremacists and other non-Muslim fanatics have killed nearly twice as many people in the United States as radical Muslims, according to a 2015 count by Washington- based research center New America.

Doggart meets the qualifications of domestic terrorism, said Amatul-Wadud and her colleague, Tahirah Clark, who are representing Islamberg in a separate civil lawsuit against the Sequatchie County, Tenn., man. But they said federal prosecutors are using nonterrorism charges for Doggart's case because the current statutes are largely aimed at foreign radical groups and not homegrown extremists. Since the beginning, protesters and activists have said a Muslim person in the same position would have been labeled a terrorist and detained pretrial - unlike Doggart, who has been on house arrest since 2015.

"That's why we asked [the U.S. Attorney's Office] for terrorism- related charges," Clark said, pointing to the government's testimony that Doggart stockpiled thousands of rounds of ammunition and customized assault weapons.

Title 18 U.S. Code § 2332a - use of weapons of mass destruction - may have applied and given the government's attorneys more leeway to label Doggart a terrorist, both attorneys said.

"Prosecutors will attempt to charge them with a terrorism- related statute," Clark said. "I believe they attempted to [in this case]. I believe they tried."

The U.S. attorneys on this case, Perry Piper and Saeed Mody, cannot comment on a pending case. But two federal prosecutors said attorneys can only work with existing charges.

"The facts of the case either sit or they don't," one said.

Federal prosecutors have successfully used terrorism-related charges before.

In 1997, they convinced a jury to convict Timothy McVeigh of domestic terrorism for bombing the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The blast killed 168 people and injured more than 500 others, news accounts show.

Two of McVeigh's convictions fell under terrorism-related charges: Conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction against persons in the United States and against federal property, and use of a weapon of mass destruction. He was executed in June 2001.

A charge geared specifically for domestic terrorists could address a double standard that negatively affects Muslims, said Clark and Amatul- Wadud, who are black and Muslim. They plan to lobby Congress for such a charge after Doggart's trial, which continues today at 9 a.m. before U.S. District Judge Curtis Collier and is expected to end Wednesday.

"You hear so many news stories about Muslims," Clark said. "This person who planned to burn a bridge lived next door and seemed to be a regular person. You know, he was a professor at this college. They may seem normal. But now look, you just can't trust any Muslims."

That narrative is often pushed in public discourse and media, Clark said, whereas white men like Doggart who claim to be Christian can casually discuss killing people in a popular diner during the lunch hour.

She was referring to a meeting Doggart had with three people at the City Cafe in Chattanooga the day before he was arrested.

"If we make it out and actually escape, you know, what does that do to all of us individually?" Doggart asked on April 9, 2015. "It's gonna change your life, whether you like it or not.

"You just don't go in and kill people and blow stuff up and then the next day, you know, go back to work and be real happy and all that."

Contact staff writer Zack Peterson at zpeterson@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow him on Twitter @zackpeterson918.