Orthopedic surgeon Dr. Tim Ballard doesn't waste time.

It has been only a few minutes since he entered the operating room on the ground floor at CHI Memorial, his elderly female patient already sedated and unconscious on the operating table, with only a knee exposed.

With no hesitation, he slices straight down with his scalpel across his patient's knee, top-to-bottom, making a cut that appears to be about 5 to 7 inches long.

He peels back the skin on either side and makes several other incisions, snipping through the tissue that holds the kneecap in place, allowing him to slide it to the side and exposing the two big leg bones, the femur and tibia, that come together at the knee.

He picks up his saw, a $6,000 tool with an oscillating blade, and aligns it with metal guides attached to the knee. With a deft move he slices off the rounded end of the femur, the thigh bone in the upper leg. A second and third cut, at 90 degrees to the first, squares off the nub of bone. He adds two more cuts to shape the bone and then slices a notch in the middle.

Ballard, his surgical assistant, and two surgical technicians are wearing light-green hoods that drape over their hospital- green surgical garb. Clear plastic hoods let them see what they are doing and prevent spatters from striking the outside of their surgical masks, which may contain germs, and falling back into the incision.

Moving to the lower leg, Ballard shears off the top of the large tibia, or shin bone and shapes it to match the back of the metal implant.

He glances at an assistant and suggests a size for the knee implant.

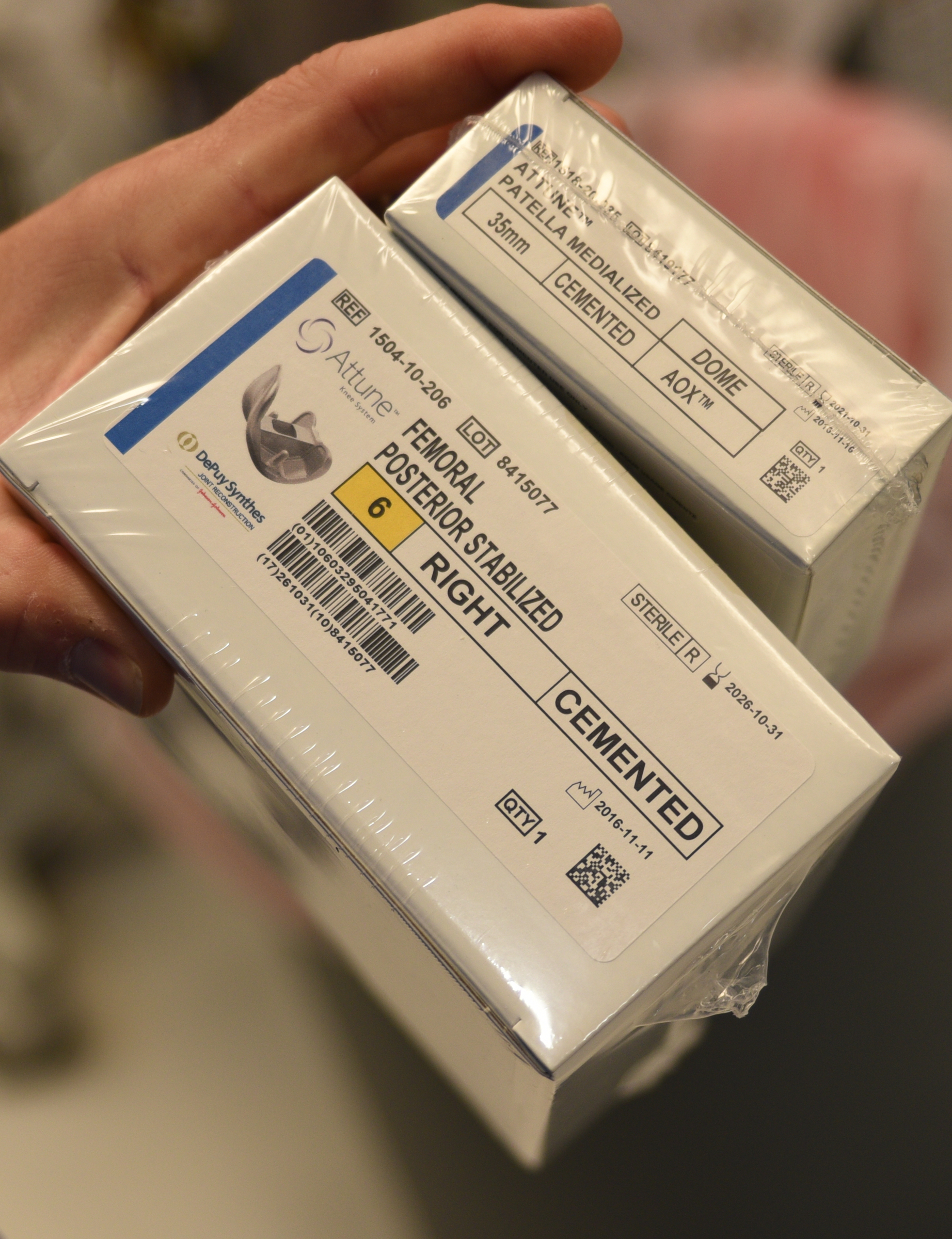

From a selection of several arrayed on a tray in front of him, the assistant selects one and hands it to Ballard. The implant, made of highly polished cobalt, is squared on the back, matching the shape of the newly shorn thigh bone, but rounded on the front just like the bone it is replacing. A depression in the middle can glide along a ridge on the corresponding implant that will be attached to the tibia.

The surgeon places the implants on the ends of the thigh bone and tibia and checks the fit. Both pieces seem to fit snugly with proper alignment.

A sleeve of high-grade plastic fits between the two pieces of metal, to replace the worn-out cartilage and connective tissue that formerly separated the bones.

Now it is time for some cement, a light-gray, claylike substance that gets hotter as it solidifies. Surgical technician Mindy Loach squeezes out a golf-ball sized blob, and Ballard applies it between both pieces of metal and the underlying bone. Then his surgical first assistant, Calvin Jackson, taps the metal with a mallet to improve the seal.

Ballard, Jackson, Loach, and surgical technician James Pinet now all fold their arms and wait a few minutes while the cement hardens.

It has been less than 20 minutes since his first incision, yet he is almost done, the 10th total knee replacement he has completed today and one of 19,000 he has done over a 20-year career.

***

As an orthopedic surgeon, Ballard is among the highest-paid doctors in Chattanooga, and for good reason.

The knee is the most complicated joint in the body, and when it is damaged, even common tasks such as standing, walking or climbing stairs can be painful. A well-done hip or knee replacement can dramatically improve a person's quality of life, relieve chronic pain and allow them to return to work or enjoy an active lifestyle.

Improvements in surgical techniques and technology over the past decade resulted in a doubling of hip and knee replacements between 2000 and 2010, to more than 690,000 per year. With people living longer and better implants, a joint replacement will be part of many people's future, said Dr. Mark Freeman, one of the top orthopedic surgeons at Erlanger hospital.

"There is exponential growth forecast for the next 20 to 30 years," he said.

Better technology means the metal and plastic components now last much longer, so a replacement may last 20-30 years rather than just 10-15, as before.

"The materials have improved; the quality of the plastic is much more durable than it used to be," said Dr. Martin Redish, an orthopedic surgeon at Parkridge Medical Center. "When knee replacements were developed in the '70s, they were made like a door hinge. Now everything has gone to mimicking the natural anatomy, because the knee does more than just bend - it rotates and has other subtle movements to it."

"It is becoming more available to younger people," Ballard said after completing his surgery. "In the old days, we were happy to get 10 years out of a joint replacement and we didn't have good redo techniques, so we tried to hold off on the operation until patients were in their mid-60s to early 70s."

Older people also are benefiting.

"I had a grandmother come to me when she was 97," Ballard said. "She was in pain and completely miserable." After her surgery, she lived to be 104. "She stayed in her own home until she was 102 - what did that save society?" he asked.

Improved surgical techniques reduce hospital stays and rehabilitation time.

"If you talked to someone 10 or 20 years ago, they would spend five to 10 days in the hospital after the surgery," Freeman said. "Now it is less than 36 hours, maybe even 24 hours for most patients."

Redish, who specializes in partial knee replacements, believes that time can be reduced even further.

Knees and hips go bad when cartilage or connective tissue starts falling apart, a condition commonly known as osteoarthritis. Sometimes only part of the knee is affected.

In a partial knee replacement, Redish makes a 3- or 4-inch incision and cuts away only the damaged portion of the knee. He uses a drill with a burr to gouge out a depression in the bone that is filled with cement and attached to the cobalt replacement part.

Because the surgery is less invasive, some patients may be able to go home without spending a night in the hospital or needing rehab.

"The money saved is incredible," he said, "not to mention the [reduced] pain and suffering."

Federal health care officials are even considering allowing some knee and hip surgeries to be done outside hospitals, in stand-alone outpatient clinics.

That proposal drew only limited support from Chattanooga orthopedic surgeons. Some patients are always going to need post-surgical care, Freeman said.

"So it might be OK to do outpatient surgery for one patient, but for an 80-year-old widow who lives on a farm in Rhea County, you might need two days in a hospital."

Ballard said he has offered outpatient surgery to some patients, "but I'm not pushing them superhard to do that."

"My No. 1 concern is not whether they are in a hospital for zero days or one or two days, but rather where you are and where you need to be."

Federal officials also have been promoting a so-called "bundled payment" plan that requires hospitals and surgeons to accept a flat fee for joint replacements. If there are complications and the patient is rehospitalized, the payment is reduced.

Whereas in the past, the doctor and hospital billed Medicare or an insurance company and handed off the patient to physical therapists or a family doctor, the bundled payment goal is to force everyone involved in the patient's care to work together to be certain the operation is a success.

A study published earlier this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association claimed bundled payment plans saved hospitals and insurers more than $5,000 per patient, and readmission rates were not affected.

Orthopedic surgeons and hospitals have been wary, concerned patient care would suffer as a result of Medicare's efforts to control costs.

Freeman said he worries doctors and hospitals will try to lower the risk of not getting paid by agreeing to operate only on younger, healthier patients with low complication risk and turning down older, more difficult patients.

"I refer to it as cherry- picking and lemon- dropping," he said.

Whether bundled payments will survive the incoming Trump administration is unclear. His nominee to head Health and Human Services, Rep. Tom Price, R-Ga., is a former orthopedic surgeon who as a member of Congress has regularly opposed government interference in physicians' decisions on care. Price has argued bundled payment plans may restrict a doctor's efforts to provide the best care possible.

Regardless of how they are paid for, Americans seem sold on hip and knee replacements.

"People don't want to live with pain or stiffness, they want to fix their physical well-being," Freeman said. "Thirty years ago, people would accept that they have to use a cane or a walker. Americans today don't accept that."