What can you do to help stop antibiotic resistance?

Use drugs as prescribedOnly take necessary antibioticsClean your handsGet routine vaccinesPrevent food-borne illnessesDrink safe waterProtect yourself from STDs

Antibiotic medications attack infectious, disease-causing bacteria, but the pathogens that antibiotics are designed to kill are learning how to fight back and threatening these essential, life-saving treatments.

In the United States, at least 2 million people per year are infected with bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics, according to a report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and at least 23,000 of those people die as a direct result of antibiotic-resistant infections.

But public health programs are fighting back, too.

On Wednesday, the CDC released its first report highlighting each state's progress since the agency provided $144 million beginning in 2016 to state and local health departments and Puerto Rico to address the crisis.

The information, displayed on the CDC website as the 2017 Antibiotic Resistance Investment Map, overviews how much money each state received to detect, respond to, combat and prevent resistant infections. Tennessee received $6,668,196 in fiscal year 2017, placing it behind only California, New York, Maryland and Washington state in the amount of money received.

"Antibiotic resistance has the potential to impact all Americans at every stage of life," CDC Director Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald said in a news release. "This interactive map showcases the work happening on the front lines of every state and CDC's commitment to keep people safe from drug-resistant infections."

This illustration released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a group of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacteria. The image was based on scanning electron micrographic imagery. In 2016, for only the fourth time in its 70 year history, the United Nations is holding a special meeting devoted to a health issue: This time, on the rise of untreatable infections that is being propelled by the way we over-use and misuse drugs in both people and animals. (Melissa Brower/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via AP)

This illustration released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a group of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacteria. The image was based on scanning electron micrographic imagery. In 2016, for only the fourth time in its 70 year history, the United Nations is holding a special meeting devoted to a health issue: This time, on the rise of untreatable infections that is being propelled by the way we over-use and misuse drugs in both people and animals. (Melissa Brower/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via AP)Michael Craig, a CDC expert in antibiotic resistance, said the Tennessee Department of Health is a leader in tackling the problem across the nation.

"They have come up with some great strategies for working with the state to address these problems, as well as working with other states," Craig said.

Nashville is home to one of seven antibiotic resistance regional labs, which are strategically placed around the nation to perform high-tech, specialty testing of emerging resistance concerns. The Tennessee lab, which accounted for $2,918,489 of the state's allocated funds, tests specimens from Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana and Puerto Rico.

"Every state does not have the capacity or the funding to do this kind of very advanced testing," said Dr. Pam Talley, deputy director for the state's antimicrobial resistance program. "That's why I think they very carefully have chosen the seven labs and divvied them up by region."

The testing identifies extremely rare and dangerous germs, like carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, better known as CRE or the "nightmare bacteria," which was found in a Tennessee hospital this fall.

That particular strain was the first of its type in the state, but the health department was able to execute containment protocol and rule out any more cases, earning accolades in the CDC's report.

"What we're trying to do with CRE is prevent it from becoming endemic or extremely common in health care settings, so that's what all of this effort is," Talley said. "In other parts of the world, it is quite common, so we are working really hard to prevent that from happening here."

Craig said the fear with CRE is that colistin, one of the only antibiotics capable of treating the infection, can be highly toxic.

"So there's sort of a trade-off of whether the person can survive without treatment or whether they need to go on colistin and potentially have some of those very, very life-threatening, bad side effects that can go along with that agent, " he said.

While CRE appears to be at bay in the state, Talley said methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, another bacterium garnering attention for drug resistance, is a significant problem.

"There's lots of ongoing work to try and get to the bottom of that and improve that situation," she said, adding that the antibiotic resistance program is highly dependent on federal money.

"The need will be ongoing, and much of this particular funding has been tied to the Affordable Care Act, so we are hopeful that the importance of this area is recognized and will continue to be supported in Washington," Talley said.

Both Talley and Craig emphasized the significance of curbing antibiotic misuse and overprescribing - a driving force in the growth of resistant bacteria - and diligent infection control, such as hand washing and staying up-to-date on vaccines.

"We are already seeing that antibiotics that we have long relied upon are no longer working," Craig said. "That certainly means that we need to develop new antibiotics and new therapeutics, but it also means that we need to be much more vigilant about detecting new forms of resistance, containing them, preventing those infections, and improving the use of antibiotics."

Contact staff writer Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.

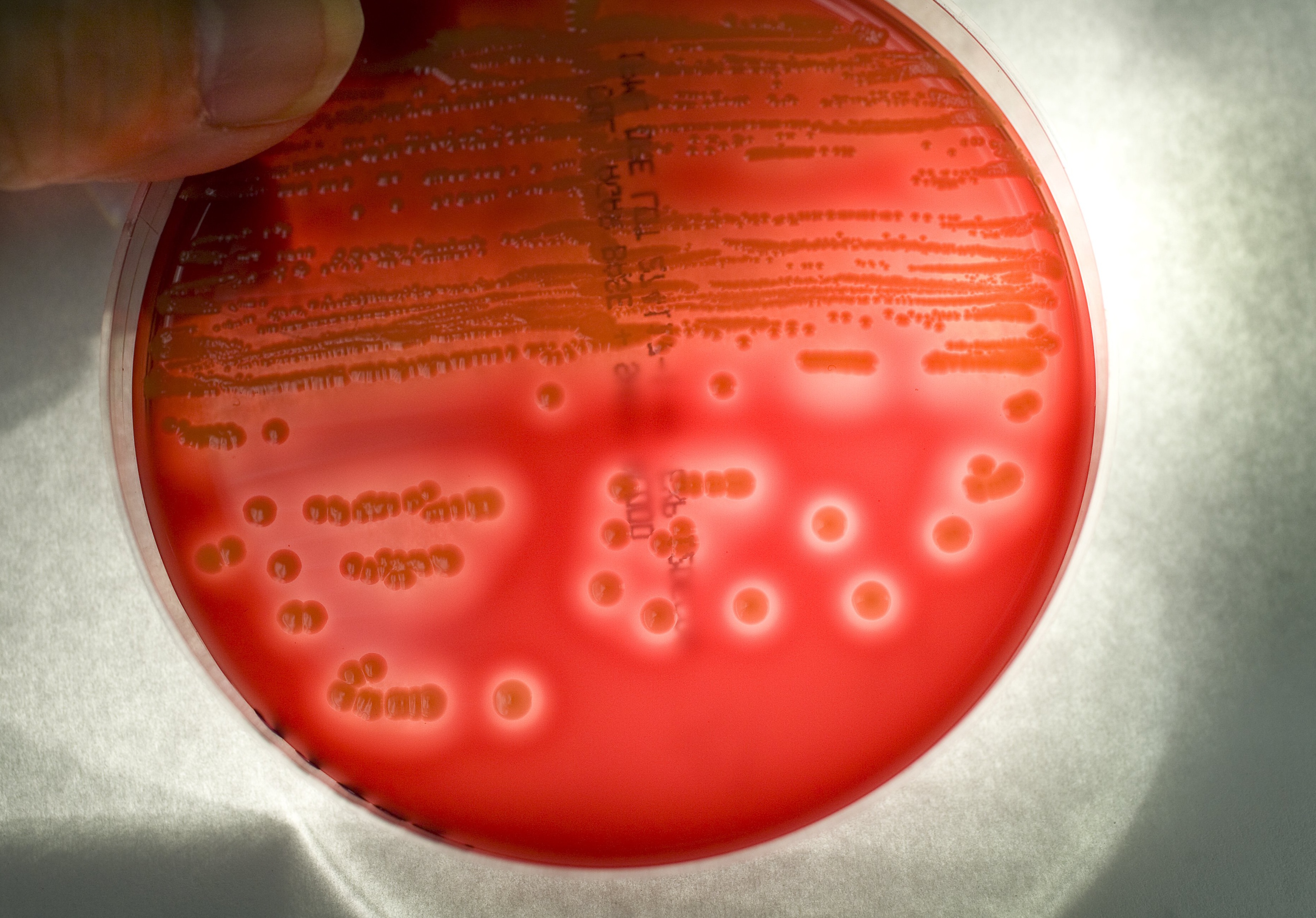

In this Nov. 7, 2008, file photo, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonies from a Seattle hospital patient grow in a blood agar plate at a local lab in Seattle. Health officials say 1 out of every 7 infections that patients pick up in the hospital is from supergerms resistant to antibiotics. The bugs include the staph infection MRSA and five other bacteria impervious to many kinds of antibiotics. (Mike Siegel/The Seattle Times via AP)

In this Nov. 7, 2008, file photo, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonies from a Seattle hospital patient grow in a blood agar plate at a local lab in Seattle. Health officials say 1 out of every 7 infections that patients pick up in the hospital is from supergerms resistant to antibiotics. The bugs include the staph infection MRSA and five other bacteria impervious to many kinds of antibiotics. (Mike Siegel/The Seattle Times via AP)