BIO

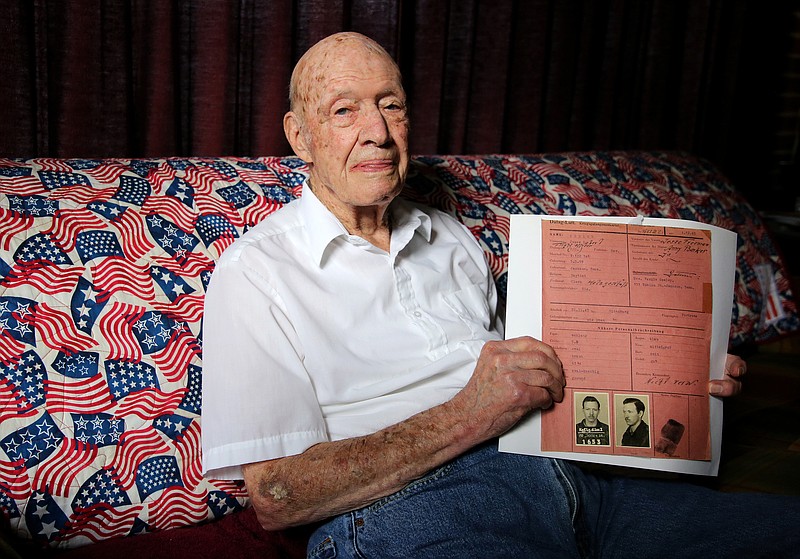

Name: Jesse SeeleyAge: 99Branch: U.S. Air Army Air Corps/U.S. Air ForceYears of service: 1942-1970

View our 21 Veteran Salute page

View our 21 Veteran Salute pageIt was 4 a.m. at the Chelveston air base in England on Nov. 26, 1943, when former U.S. Army Air Corps Flight Officer Jesse Seeley was awakened and ordered to fly.

He would be flying with a different crew than his own as a replacement for a sick navigator. Their target? Bremen, Germany.

The crew flew out over the North Sea but hit heavy flak and lost an engine of their B-17.

They were able to drop their bombs on the target, but on their way back, they couldn't keep up with the formation and became a sitting duck for the enemy.

"The fighters always like to pick on the stragglers," the 99-year-old said.

Enemy forces first attacked the nose of the plane, but Seeley and the bombardier fired back and fended them off.

What Seeley and his crew didn't know, though, is their tail gunner had bailed out. So when the fighters came back and started attacking the tail of the plane, there wasn't anyone there to fire back.

Enemy forces fired 20 mm shells, ripping through the plane, knocking another engine out and wounding two waist gunners. The plane went into a steep dive and lost about 13,000 feet in altitude before the pilot pulled them out of the dive and ordered everyone to bail out.

Seeley landed in a tree, a long way from where the plane went down. He unbuckled his parachute and climbed down, hiding under some bushes. Soldiers walked within a few feet of him, he wrote in an essay of his experience, but they eventually left without finding him.

"I thought I was going to get away and head for France that night. Being a navigator, I could navigate by the stars," he told the Times Free Press.

But all of a sudden, he looked up and found himself staring down the barrel of a rifle. The soldier had used a dog to track him down.

"That was the beginning of my being a POW," Seeley said.

They took him to an army post in Oldenberg, Germany, where he spent the night in a cell. The next day, they put a group of them in a train car and sent them to Dulag Luft, a prisoner of war transit camp.

The first thing the Germans did was remove Seeley's shoes and confine him to a 5-foot-by-8-foot cell with only bread and water. He stayed there in solitary confinement for six days.

"All I had to do was lay there day and night," he said.

He was then taken to another area of the camp where he was interrogated by a German officer.

A big map was on the wall and showed the course Seeley's crew was flying.

"I looked up at it, and [the officer] says, 'Does that look familiar?'" Seeley said. " I said, 'I don't have any idea what course we were flying.' He said, 'Oh yes you do. You were the navigator.' I said, 'Well, you don't know that.' And he said, 'Oh, yeah I do. I've already established you were the navigator.'"

The officer was nice to Seeley at first, even offering him a cigarette. But when he realized Seeley wasn't going to cooperate, he told him, "We haven't notified anybody yet that you're a prisoner of war, and we wouldn't have to notify them."

In other words, they could do whatever they wanted to with him and no one would know. But finally, the officer ended the interrogation and Seeley was taken back to solitary confinement.

He was then moved to another transient camp before being sent to Stalag Luft 1, a permanent camp. He stayed there in block 2, room 8 for the next 17 months.

His wife, Vergie Seeley, gave birth to their first son, Jesse Seeley Jr., in May 1944. Jesse Seeley didn't learn he had a son until two months later.

It wasn't until late April 1945 that Seeley was liberated.

He and his comrades heard artillery fire in the east, and they knew the Russian army was approaching. The next day they woke up to find the German guards were gone, and the Russians arrived a short time later.

But Seeley didn't get to go home until much later. There weren't enough ships to transport the roughly 100,000 soldiers living at Camp Lucky Strike. Seeley finally got his turn in late June and docked in Hampton, Virginia.

"Of course, the first thing I did was call my wife," he said. "That brought me some sad information. She told me my brother, James Albert [Seeley] was missing in action. He was over the South Pacific."

Seeley finally retired in 1970 as a master sergeant and now lives in Red Bank. He and his wife were married for 74 years and had three more children - James, Sharon and Phillip - before she died in 2017.

Contact staff writer Rosana Hughes at rhughes@timesfree press.com or 423- 757-6327 with tips or story ideas. Follow her on Twitter @HughesRosana.