More Info

If you go:The meeting is free and open to the public. It starts at 6:30 p.m. at the First-Centenary United Methodist Church at 433 Oak St.

In step with other major Tennessee cities and states, a Chattanooga group is starting a community bail fund to ensure people don't languish in jail on criminal charges simply because they can't afford to be released.

Half of the 1,708 inmates in Hamilton County haven't been convicted of their charges, and yet they are losing employment, time with their families and medical stability because they can't make bail. As they wait for their cases to be resolved, legal experts say, defendants are more prone to accepting plea deals to go home, even though they could fight the charges and get them dismissed. In the meantime, taxpayers are footing some of the daily bill to house them.

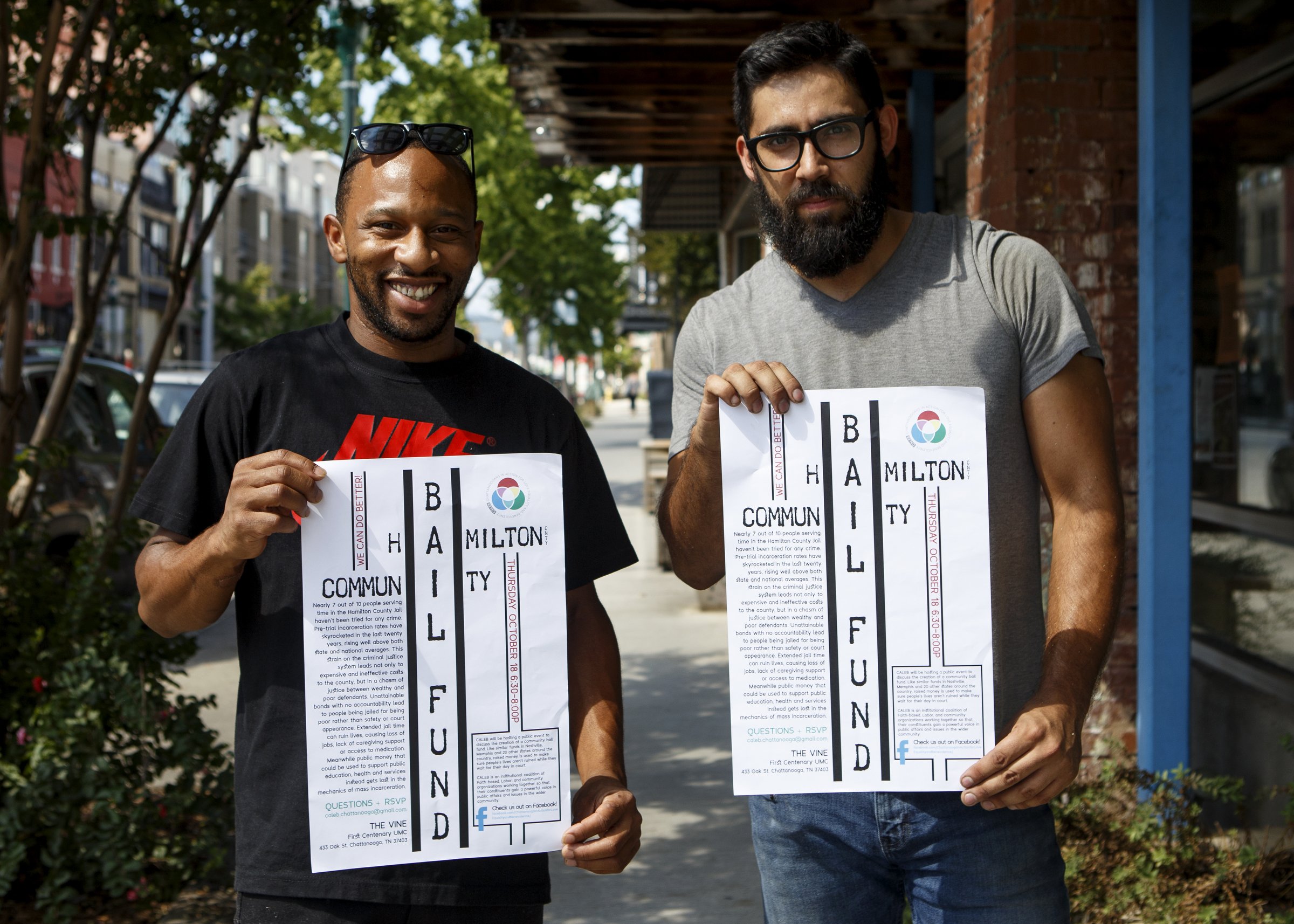

That's the reality for poorer criminal defendants, according to Chattanoogans in Action for Love, Equality and Benevolence, or CALEB, a faith-based nonprofit group that's hosting a public event Oct. 18 at First-Centenary United Methodist Church at 6:30 p.m. to further explain the idea. But defendants with more money can buy their way out, resulting in a "chasm of justice between wealthy and poor defendants," the group says.

"An unconvicted defendant with more money who is a higher risk to public safety and unlikely to show up in court can buy their way out," the organization wrote in a news release. "On the same day, a poor unconvicted defendant that has community references, is a low risk to public safety and is highly likely to show up for court cannot make bail. This ineffectiveness is causing states to begin substantial reform."

Bail is the fixed amount of money a judge sets to ensure someone's appearance in court, and it's not meant to be punitive. Though judges consider multiple factors, including a person's prior record, their financial means and their likelihood of conviction on their current charges, they primarily look at a person's community ties and their risk to public safety.

There's no doubt some people are in custody because of violent allegations - not just because they can't afford bail. The process of getting a bond is multifaceted, and defendants can get stuck in custody along the way because of many factors: Long processing times or mistakes at the overcrowded Hamilton County Jail, rules that give judges the discretion to withhold a bond on probation violations, and competing bond companies that make judges wonder whether the initial bonds they set are being followed.

But some defendants simply can't afford the 10 percent premium you have to pay to a bondsman to post bail. If a judge sets your bond at $5,000, a person has to come up with $500.

Across the nation there's been a growing movement to offer more pretrial services, end cash bail and start community bail funds. In August, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill ending cash bail. Under the new system, those arrested and charged with a crime won't have to put up money or borrow from a bail-bond agent. Conversely, judges will decide who to release or keep in custody, which critics say gives them too much discretion and power.

Here, the jail costs an estimated $87,000 to run daily, and Hamilton County pays millions of dollars a year to CoreCivic to operate the Silverdale Detention Center. CALEB says public money can be better spent on public education and health services instead of getting swept up in the mechanics of mass incarceration.

When a person is arrested, they first are taken to the Hamilton County Jail for a laundry list of processing.

"You go through to see the magistrate, take your fingerprints, go over a questionnaire, take your picture, get your wristband, and then, if your bond is paid, you can get out," said Allen Shropshire, a CALEB member who works at green|spaces in Chattanooga. "But it's not like that. I've spent all night there before, and I didn't have any holds."

The magistrate is a judge who works in a brick cubicle connected to the jail, and they're on duty 24/7. Although there are generally accepted bond amounts for a crime, each magistrate handles things differently and is working off limited information. Magistrates don't have access to a defendant's full criminal record, and the only witness they typically hear from is the arresting officer.

Since lawyers or advocates are rarely at these bond hearings, the defendant faces a one-sided situation, said Chattanooga attorney Josh Weiss, who has practiced about eight years in Tennessee and Georgia. "You essentially have to be there when your client is booked and processed, which is extremely rare or difficult to do. I've been to one of these hearings, otherwise you don't really go."

Felipe Lara, a CALEB member who has studied Hamilton County's system since the summer, said public bond information doesn't show everything that influences a magistrate's decision. For instance, he said, an officer may testify that a defendant belongs to a criminal gang. Or the arresting officer may offer testimony on how well-behaved or cooperative they perceived a defendant to be. Both influence the bond amount, Lara said.

Marie Mott, an activist who hosts a show on NoogaRadio 92.7 and works with Concerned Citizens for Justice, said a magistrate gave her a $10,500 bond after Chattanooga police arrested her in January on a felony domestic assault charge. Mott, who had no prior record or convictions, said she was defending herself from a drunk family member who tried to grab her and then called authorities on her. Aside from repeating her self-defense story, Mott said she didn't speak to one of the six responding officers and was placed in handcuffs because of her lack of cooperation.

At the jail, Mott said, she called her parents and they agreed to make her bond. Because of the domestic charge, she had to remain in custody on a 12-hour hold. But out of nowhere, she said, officers took her and five other women out a side door, led them into a van and drove them in the middle of the night to Silverdale. Women are frequently transferred to that facility, since the jail isn't equipped to hold women.

At Silverdale, Mott said she slept on a concrete floor, without a blanket, cold air blasting in the facility during the winter. Several hours passed before her paperwork was processed and she was released. During that time, Mott said, "nobody asked us if we're hungry, thirsty, need a blanket. Nobody asked if we need medicine."

Prosecutors later dismissed her charge.

While there isn't a hard-and-fast rule about it, magistrates appoint a public defender for "the vast majority" of people who remain in jail after 24 hours, Hamilton County Public Defender Steve Smith wrote in an email. Smith's lawyers handled nearly 15,000 appointed cases in Hamilton County General Sessions Court, which is where defendants make their first appearance before a judge.

Once they're in custody, they are supposed to see a judge within 14 days.

At that time, a General Sessions judge can reduce a defendant's bond, release them on the promise they'll return to court, or assign them to the county's pretrial GPS and alcohol monitoring program. There are about 200 people in those programs, said Chris Jackson, director of the county's corrections department. But the county doesn't own that equipment, which means there's a $45 monthly charge to defendants to offset that cost.

The idea behind the community bail fund, CALEB says, is the organization will raise money through private donations, hopefully partner with the Public Defender's Office to identify people who can't afford their bail, and then ensure they get to court. As long as defendants return, the money will be returned and roll over to the next person who needs help. CALEB says it doesn't expect to pay someone's bail over $5,000 while it's starting out raising money. But the organization has studied similar programs in Nashville and Memphis, has begun taking donations and has met with Smith, the public defender.

"In Nashville, 97 percent of the people they've helped have shown back up to court on time," said Michael Gilliland, another CALEB member. "We hope the the idea of these funds being able to roll over to the next person is a remarkable impetus for people to show up."

Contact staff writer Zack Peterson at zpeterson@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow him on Twitter @zackpeterson918.