From trying new drugs to changing how they use ventilators, Chattanooga area clinicians have become a lot better at treating COVID-19 patients since the early days of the pandemic.

Even though most people don't need medical care to recover from the coronavirus, COVID-19 is a highly contagious, new disease that's more serious and deadly than influenza. The virus prompted drastic public health measures and fueled a worldwide scramble, which is ongoing, to find effective treatments.

There was no specific antiviral drug for COVID-19 when the pandemic began. Many potential pharmaceutical treatments, such as hydroxychloroquine, came out of the gate but wound up ineffective.

Providers were left to treat severely ill patients with standard medications, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, to ease symptoms and supportive care such as supplemental oxygen. Although they still rely heavily on these treatments in COVID-19 care, now physicians better understand when and how to use them.

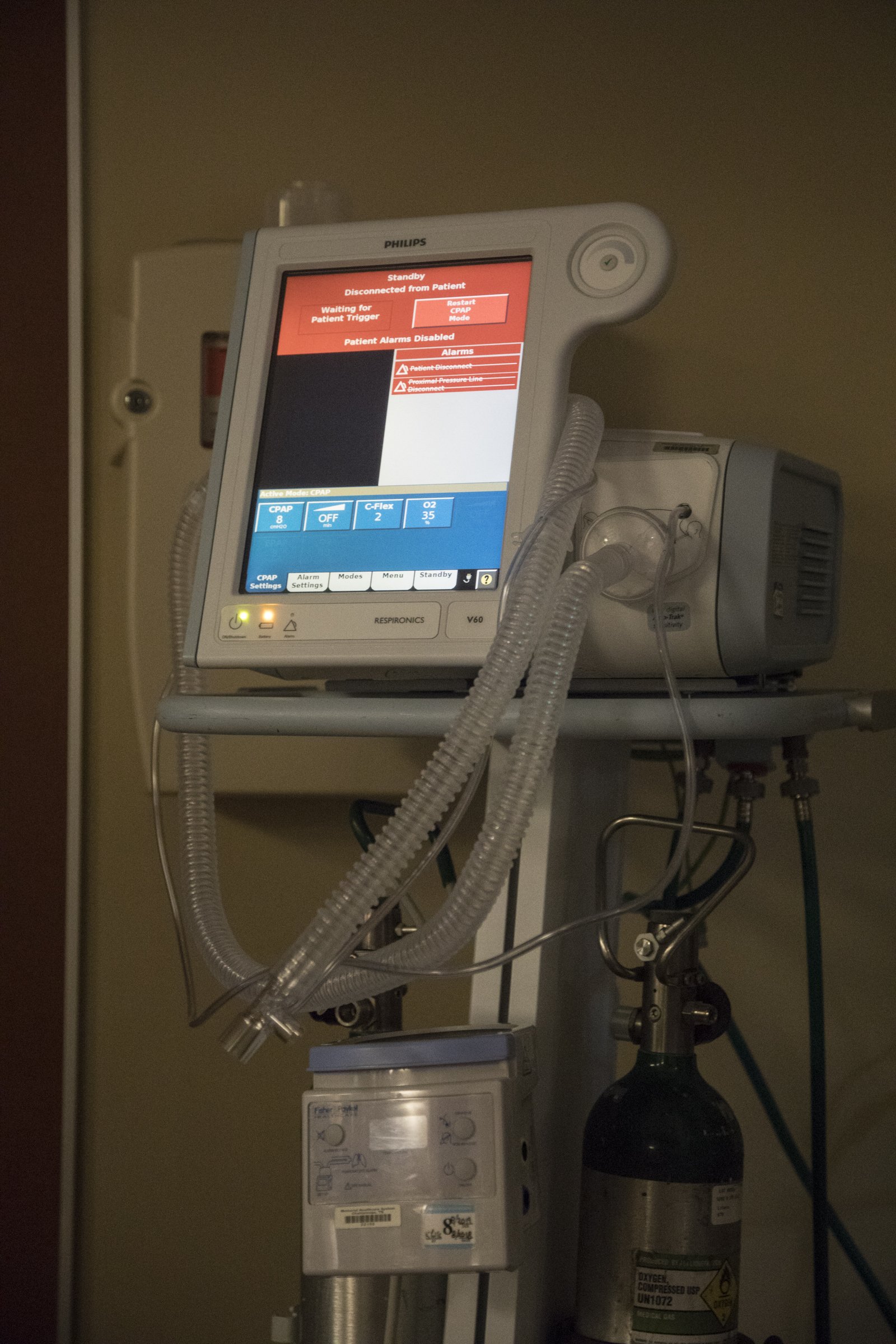

Ventilators - machines that assume the role of breathing when the lungs can't function - became an early symbol of the pandemic (as well as impending death) after horror stories of overwhelmed hospitals in Italy and New York surfaced in the media.

But much has changed in the eight months since the coronavirus was first detected in Wuhan, China. Mortality rates are declining, some treatments are showing promise and providers are constantly finding ways to better treat the sick.

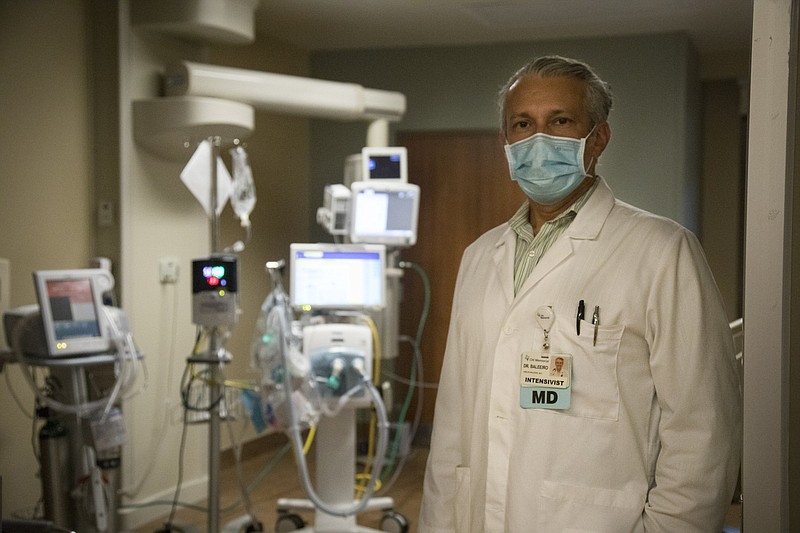

"This is a new disease, or a novel disease, that was not here a year and a half ago, so we have been learning from our experiences as well as the published experience from other communities and other large health systems," said Dr. Carlos Baleeiro, pulmonologist and medical director of critical care at CHI Memorial Hospital.

While it's true that overall mortality trends have improved, Baleeiro said he attributes that in part to more young, healthy people - who typically weather the course of disease without much trouble compared to vulnerable older adults - becoming infected.

However, evolution in the way clinicians manage COVID-19 is also a major factor, said Dr. Jigme Sethi, a pulmonary critical care specialist at Erlanger Medical Center.

When the disease first hit the coasts of the United States, one of the main debates was over if and when a patient who was struggling to breathe needed to be placed on a mechanical ventilator.

"Earlier, we would intubate [place on ventilators] patients much faster, maybe when they first presented and were short of breath and short of oxygen," Sethi said.

"Now, we're trying our level best to delay putting them on ventilators, because many of them do recover with the treatments we are using," he said. "But clearly, there's a proportion that need a ventilator, and in them, the risk of dying is particularly high."

It's a bad sign when a patient is sick enough to need a ventilator, no matter the disease. However, early mortality rate reports for COVID-19 patients requiring ventilation exceeded 50% - significantly higher than the published mortality rates ranging from 35% to 46% for patients intubated with H1N1 influenza pneumonia and other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome - according to a May study in the Journal of Critical Care Medicine. That same study found that mortality rates for intubated coronavirus patients was closer to 36%.

Baleeiro said there are many advantages of delaying ventilator use if possible and instead opting for the less-extreme, conventional oxygen therapy or high-flow oxygen.

"When somebody is on the ventilator, by nature of how much more invasive it is, they require a lot of sedation," he said. "They can't participate as much in their care and become more dependent on full care by the staff, and their recovery can sometimes take longer."

Patients who aren't intubated are able to move around more, which is thought to speed recovery. For patients who must be on ventilators, "proning" - positioning patients on their stomachs - is also proving helpful. The treatment can be used on patients who are fully awake, as well.

"If you're just lying flat, what's happening is the inflammation and the fluid is all staying in the same space in the back of the lungs. But when we mobilize, and when we change position, you are hopefully rotating and expanding different parts of the lung," Baleeiro said.

"And there is a concern, though there's not scientific agreement, that the excess pressure of being on the ventilator in this particular disease may worsen inflammation and may make the course of the disease longer and more difficult," he said.

Aside from the unknowns that come with a new disease, treating coronavirus patients is complicated. The virus is known for causing pneumonia and respiratory failure, but it affects the kidneys, the heart, the brain and neuromuscular systems, as well as increases the risk of blood clots, Sethi said.

"COVID-19 has manifestations that are more varied and more severe than anything we've ever seen," he said.

For example, Baleeiro said patients with COVID-19 seem to be at higher risk for developing "clotting complications" than other respiratory patients.

"We have seen a lot of these patients come in who develop blood clots in their legs, or blood clots in their lungs," he said. "We obviously have tests to look for those, but we have also created a protocol where if patients have laboratory abnormalities that make them more likely to have clotting complications, we are using a protocol to start them on blood thinners."

So far, the experimental drug remdesivir is the only antiviral drug to show potential success in limiting coronavirus infection by targeting a protein that allows the virus to replicate. It was granted emergency use authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in May for patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 based on two randomized trials.

Sethi called the drug "an extremely important therapeutic advance" when used along with a daily dose of decadron - a well-known corticosteroid also called by its generic name dexamethasone - to quell inflammation. Chattanooga's three hospital systems acquired remdesivir through the government shortly after it became available in May and have been using it ever since.

"We think it is reducing the number of patients who need to go on mechanical ventilation, and it's certainly helping turn them around faster," Sethi said.

Baleeiro said his group also regularly uses the drug in patients who meet the criteria for use, and he remains cautiously optimistic.

"The data seems to be good, and it has a mechanism of action that makes sense, because it is a direct antiviral," Baleeiro said. "But I can tell you that we have treated patients who did well but still took a long time to recover. ... It's not something we can tell as soon as we give it."

Remdesivir's manufacturer, Gilead Sciences, is seeking approval for use in moderately infected coronavirus patients despite mixed trial results.

While there's still much to learn, Chattanooga's hospitals have been more fortunate and better prepared to handle COVID-19 than cities whose patient surge came earlier, Baleeiro said.

"Some other communities, they had to learn on the go with no data, no guidance," he said. "We're still learning as we go, but when our peak started we could discuss and review write-ups of the data from the other sites."

Dr. Robert Magill, medical director of hospitalists at Parkridge Health, said in an email that while some patients require a few treatment options, others need the full gamut: remdesivir, supplemental oxygen, antibiotics to treat secondary infection, the steroid dexamethasone and convalescent plasma (which is the liquid part of blood collected from recovered COVID-19 patients). Convalescent plasma contains antibodies that might help people who are struggling to overcome the disease fight infection when all other options have been exhausted.

"There is still a lot to be learned about the recovery process and complications associated with COVID-19," Magill said, adding that trying to understand the lingering issues of some coronavirus survivors, such as fatigue and shortness of breath, is another new frontier for the medical community.

"As far as future treatments, the most promising possibility, to me, is the vaccine," he said. "If we can prevent people from getting COVID-19, it will be better for all of us."

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or follow her on Twitter @ecfite.