Earlier this week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned the American public to prepare for an outbreak of novel coronavirus, which has spawned more than 80,000 cases around the world but relatively few cases so far in the United States.

As of Wednesday afternoon, there were 59 confirmed cases in the U.S. - a country home to 328.2 million people - and no reported cases in Tennessee, Georgia or Alabama, according to data released from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus map. Forty-two of those confirmed cases were passengers on the Diamond Princess cruise ship from Japan who are now isolated in hospitals.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the National Institute for Health's infectious disease chief, noted that while few cases of the new coronavirus have turned up in the U.S. from travelers outside the country, "we need to be able to think about how we will respond to a pandemic outbreak."

"It's very clear. If we have a global pandemic, no country is going to be without impact," Fauci said.

A pandemic can range in severity but is used to describe outbreaks that involve the continual spread of an infectious disease from person to person in multiple regions and hemispheres throughout the world simultaneously.

(MORE: Trump says US 'very ready' for virus; Pence to lead response)

The world has faced four flu pandemics, which occur when a new strain of the virus emerges, since the beginning of the 20th century: the 1918 Spanish influenza, the Asian flu in 1957, the influenza A (H3N2) virus in 1968 and a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus that appeared in 2009.

Becky Barnes, Chattanooga-Hamilton County Health Department administrator, said the health department works with community partners on a regular basis to prepare for infectious disease outbreaks and potential pandemics.

"We're meeting with various partners, we're all discussing what's in the plan, what might be different about this," she said, noting that the initial local response to coronavirus focused on education and awareness.

"When the novel virus emerged, there were specific criteria for screening and things that we wanted emergency departments to be prepared for," she said. "Now, we're at the point with the hospitals and other providers to discuss different aspects of the emergency preparedness plans that they all have."

Barnes said there are "certainly similarities" between the novel coronavirus and the H1N1 pandemic - commonly called swine flu - that emerged in 2009.

"It's a respiratory virus, newly emerging," she said. "I think the difference with H1N1 was we had a vaccine pretty quickly and we had some antiviral [drugs]. At this point, we don't have either one of those [for coronavirus], so you're just treating symptoms - you don't have any medicine, per se, in your arsenal."

Other times that Barnes recalls similar preparations locally were during the 2014 West Africa Ebola epidemic and when smallpox emerged as a potential bioterrorism threat.

"There was a vast amount of work," she said. "Thankfully, we didn't have an Ebola patient to deal with, but our community was ready and prepared."

The world was taken by surprise 102 years ago when the 1918 Spanish flu struck globally and locally in Chattanooga. The CDC estimated that one-third of the world's population became infected with that virus.

It's estimated the 1918 Spanish flu's death toll reached between 20 million and 50 million people. More than 675,000 Americans were sickened, 8,000 of those in Tennessee, but some estimate the mortality was much higher because many deaths likely went unreported.

Dr. Mark Anderson, an infectious disease specialist at CHI Memorial, said in 2018 that the movement of soldiers and depleted supply of medical staff because the world was at war created the "perfect storm" for a pandemic in 1918.

"It's just terrifying, absolutely terrifying," he said. "Can that happen again? I certainly would not say anything is impossible."

Soddy-Daisy woman Dora Sowell survived the Spanish flu when she was just an infant living with her family in Argentina. Sowell hasn't taken any chances since then, receiving an annual flu shot every year since the 1960s and encouraging others to get one, as well.

"I've always worried about any time the flu comes around, because I don't want to have it again," she said in 2018. "At my age, it probably would be a killer."

(Read more: Local History Column: October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic)

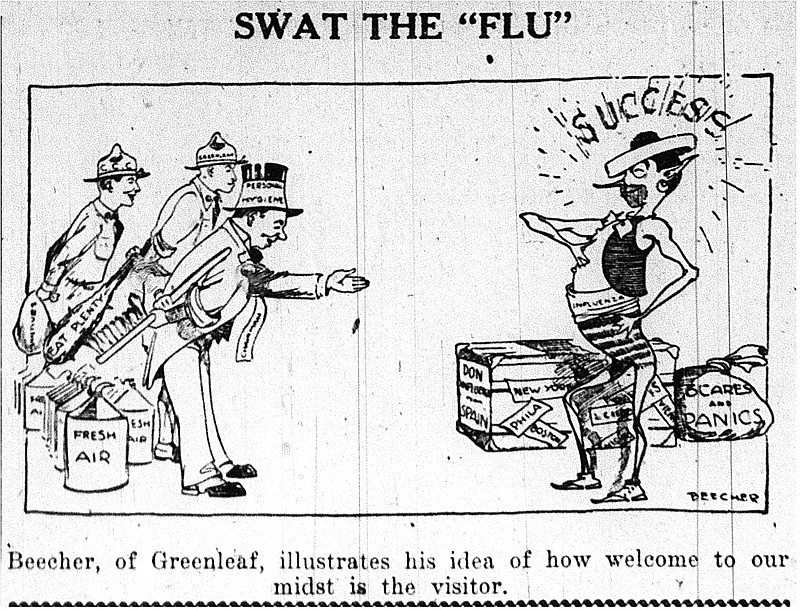

In the Chattanooga area, the first Spanish flu cases appeared at Camp Greenleaf - a medical officer training site during the war - in Fort Oglethorpe, when 26 soldiers fell ill.

The city saw 40,000 influenza cases and 392 deaths during the epidemic, with an additional 10,000 cases and 267 deaths occurring at the Old Hickory powder plant, a prominent DuPont factory outside Nashville that produced smokeless powder for the war.

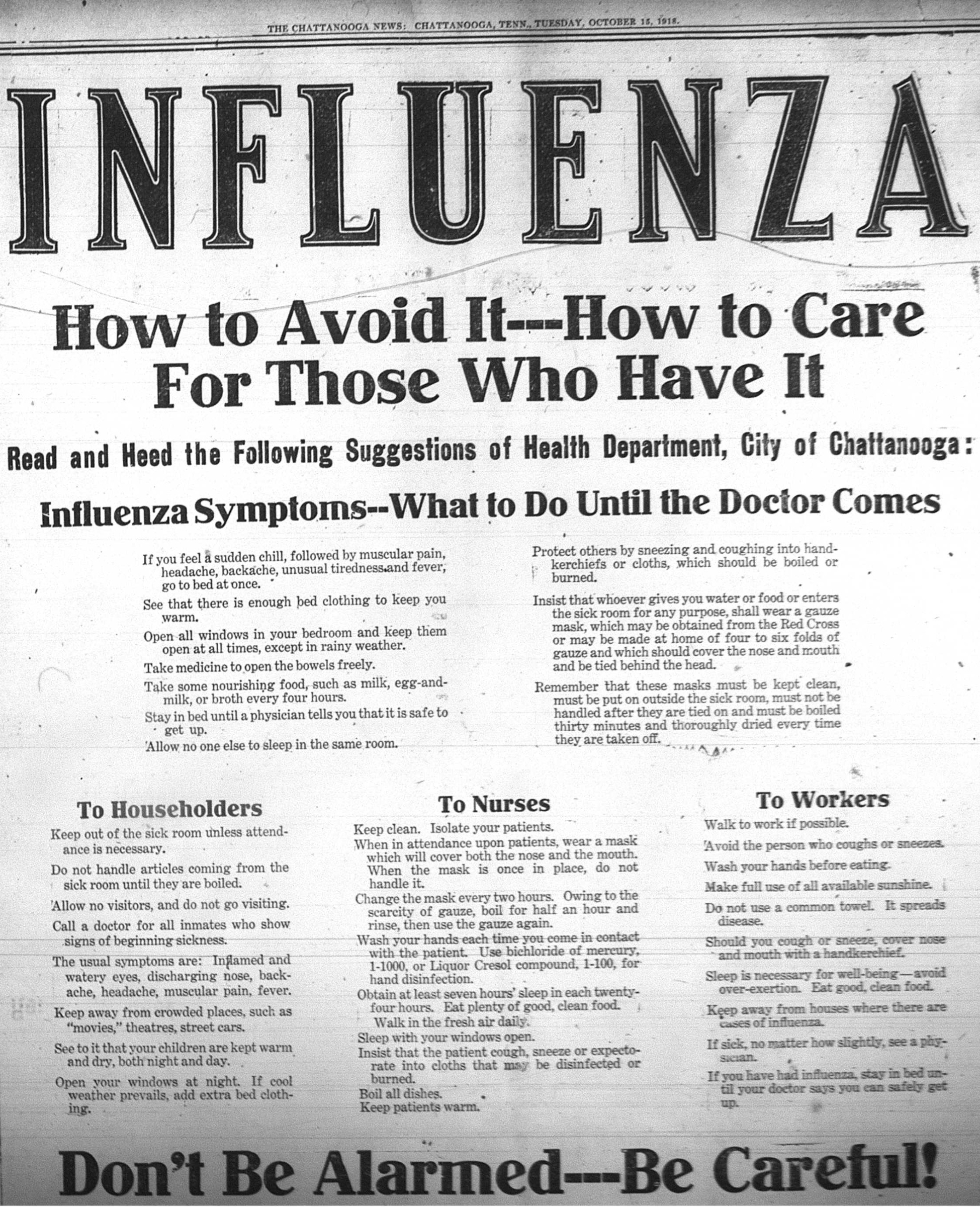

In 1918, the dangers of the influenza virus - at the time often called "grippe" - were nothing new. And flu shots, antiviral drugs to fight the pathogen or antibiotics to treat potential secondary infections like pneumonia didn't exist. While we now have vaccines and medicine to combat influenza, Fauci cautioned that it could be about a year to a year and a half before any coronavirus vaccine would be ready for widespread use.

In some rare instances, an animal influenza virus can mutate so that it can infect humans. The same is true for coronaviruses, and this is suspected to have occurred for the virus causing the current coronavirus outbreak, named COVID-19. The 1918 influenza pandemic was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. When a virus is new, there is little or no pre-existing immunity in the human population, according to the World Health Organization.

There are seven known strains of human coronaviruses, including those that can cause the common cold as well as more serious illnesses such as SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, and MERS, or Middle East respiratory syndrome.

(Read more: Coronavirus hits the floorcovering industry, China production takes economic hit)

Should coronavirus reach Chattanooga, Barnes said that good health habits - washing hands, staying home when sick, covering your cough - will help prevent further spread.

"Those are the kind of things that will keep our community healthy and safe from a lot of things," she said.

If the coronavirus were to spread throughout Hamilton County, school closures and canceling large events are possible tactics that could be implemented.

"Those are all things that can be done in the future, and those are things that our community would be prepared to do," Barnes said. "But the important thing for individuals to do right now is stay healthy on their part."

Staff writer Allison Collins contributed to this story.

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.