Long a subject of speculation and intrigue, the life and mysterious disappearance of former Teamsters President Jimmy Hoffa has drawn new interest with the release of the Netflix movie "The Irishman." But what that film doesn't highlight is the role Chattanooga played in the union boss' downfall and how a young federal judge from Signal Mountain may have played a part.

Hoffa's 1964 federal trial for jury tampering and conviction in Chattanooga put the Scenic City in the national spotlight, even as the Beatles were taking America by storm that spring.

"If you're in the legal community, it's the biggest-ever Chattanooga trial," according to Maury Nicely, local attorney and author of "Hoffa in Tennessee." "This was a time when the president of the Teamsters was widely regarded as the second most powerful man - behind the president - in the United States.

"It was a big deal, and it's still big news."

CIRCUS COMES TO CHATTANOOGA

Hoffa became president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union in 1957. He ran the trucking union with an iron hand.

Over the years, he was widely suspected of being involved in organized crime and was almost constantly under investigation by federal authorities.

He went to trial multiple times on various charges - including fraud, racketeering, illegal loans using Teamster pension funds and jury tampering - in the 1950s. But somehow, he always seemed to find a way to avoid prosecution.

MORE ON HOFFA

“The Irishman,” starring Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel, is available on Netflix.“Hoffa in Chattanooga,” written by Maury Nicely, is available is available online or through local bookstores and is published by the University of Tennessee Press.

During one of Hoffa's earlier trials, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy declared he would jump off the top of the U.S. Capitol if there wasn't a conviction.

Then, after yet another acquittal, Nicely said, Hoffa's legal team sent Kennedy a parachute to mock him.

By 1962, Hoffa appeared to be headed to another legal victory when his federal trial in Nashville ended in a hung jury. The case involved accusations he took kickbacks from businesses through a trucking firm named TestFleet - which was registered under the name of Hoffa's wife and the wife of a business partner - in return for ending a labor dispute.

But allegations that Hoffa's team had bribed and influenced jurors resulted in a new indictment for jury tampering.

The judges in Nashville were forced to recuse themselves from the case and the trial was moved to the Chattanooga courtroom of Frank Wilson, a 47-year-old from Signal Mountain.

Wilson, appointed by President John F. Kennedy, had been on the federal bench for less than three years.

At the time, Chattanooga had a strong union presence, which made it an attractive venue for Hoffa and his team, according to Nicely. When Hoffa arrived at the Chattanooga airport for the trial, a large crowd of supporters met his plane holding pro-Hoffa signs.

Chattanooga-based Teamsters Local 515 was seen as a rough union with ties to bombings, money laundering and other illegal activities, highlighting the tensions that the trial brought to Chattanooga.

"We were regarded as a labor town," Nicely said.

From the beginning, the trial was a circus.

National media and local spectators crowded downtown to see and hear the notorious union leader.

"The national news descended on town when the trial began," Nicely said. "Every time Hoffa would walk from his room at the Hotel Patten [now Patten Towers] to the courthouse, just a swarm of cameramen and reporters would be following him.

"In an age before the sound bite, Hoffa was a walking sound bite. He was always good for some off-the-cuff comment that made good press."

In Arthur Sloane's 1991 biography "Hoffa," the union leader is quoted as saying, "I do to others what they do to me, only worse."

Every day of the trial, spectators would line up to get a seat in Wilson's courtroom in what is now known as the Joel W. Solomon Federal Building and United States Courthouse next to Miller Park on Georgia Avenue. To keep from losing their seats, spectators would bring lunch to court until Wilson prohibited food in the courtroom.

Hoffa's legal team - which included local attorneys Harry and Marvin Berke, the grandfather and father of Chattanooga Mayor Andy Berke - took over the top floor of the Hotel Patten, allegedly bringing in a full law library.

Just a few blocks away on Broad Street, the federal prosecutors and the sequestered and heavily guarded jury were housed at the Read House hotel.

THE YOUNG JUDGE

Managing the trial fell to Wilson, who was highly respected despite his relative youth and inexperience as a federal judge, according to Nicely.

With Hoffa's team being notorious for dirty tricks and alleged criminal activities, Wilson's first concern was the safety of his family.

"I was a young guy and had no appreciation of what my dad was going through," said Randy Wilson, son of Frank Wilson and just 8 years old at the time of the trial. "But what I did know - and I thought it was pretty cool - was that I had U.S. marshals driving me to school every day. And we had U.S. marshals living with us throughout the trial.

"I didn't know this at the time, but Dad's only real concern for the family was that they might try to kidnap me or my brother."

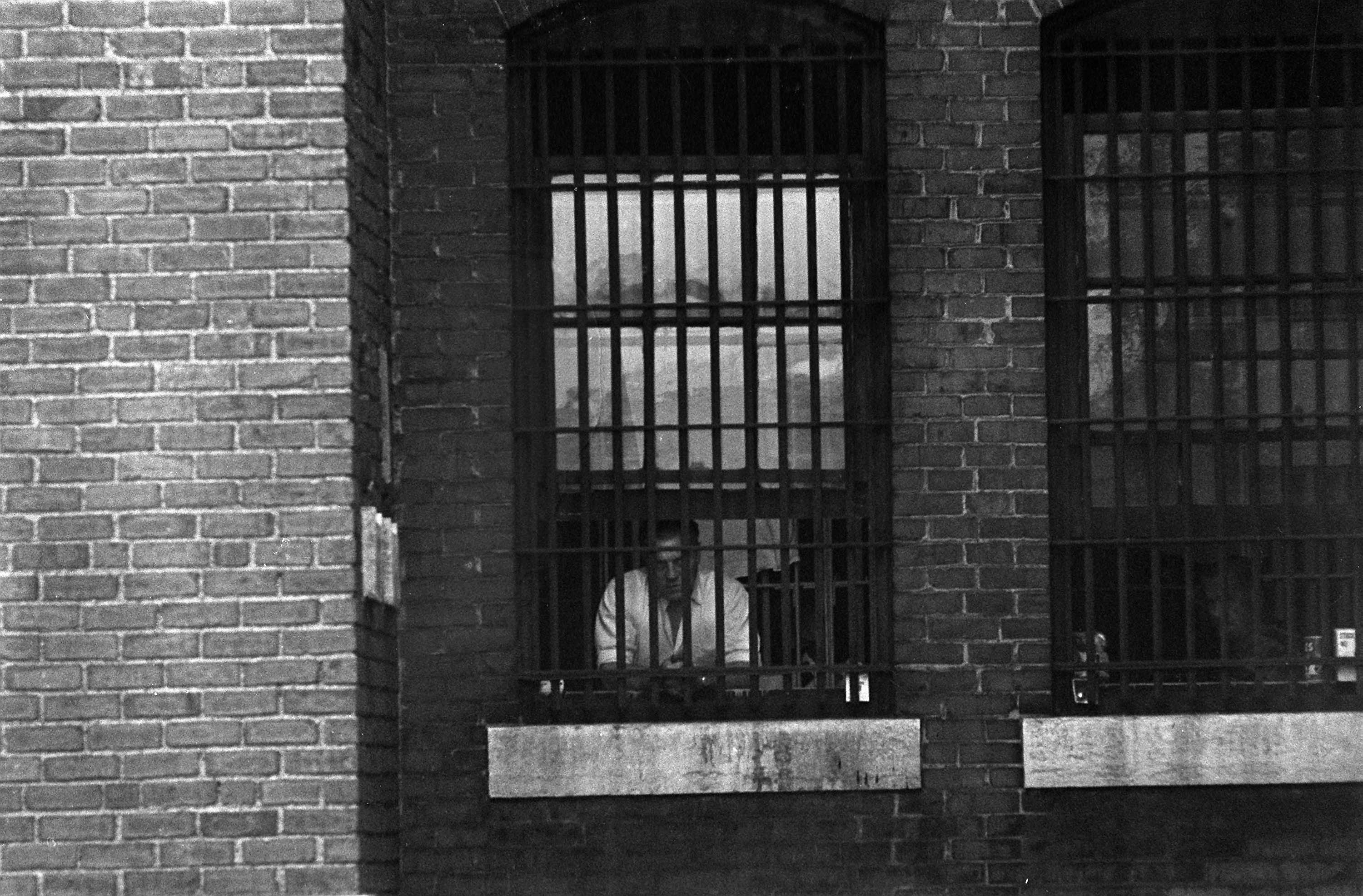

Teamsters Union president James R. Hoffa leans on the window sill as he watches the scene outside his cell in Chattanooga, Tenn., Monday morning May 5, 1967. Hoffa was being held in the Hamilton County jail awaiting a hearing on his fourth motion for a new trial on jury-tampering charges. (AP Photo/Charles Kelly)

Teamsters Union president James R. Hoffa leans on the window sill as he watches the scene outside his cell in Chattanooga, Tenn., Monday morning May 5, 1967. Hoffa was being held in the Hamilton County jail awaiting a hearing on his fourth motion for a new trial on jury-tampering charges. (AP Photo/Charles Kelly)Judge Wilson faced challenges in the courtroom, as well.

Hoffa's legal team took every opportunity to disrupt the trial in an attempt to force a mistrial through disruptive outbursts and numerous objections.

Wilson worked late into the night reading over each day's testimony to ensure that the trial remained fair and error-free.

"For six weeks, he didn't go to bed before 3 o'clock in the morning," Randy Wilson said of his father. "That's all the more remarkable when you have people trying to intentionally cause the judge to lose his cool and blow a gasket. That anybody could stay up that late for that many weeks and still maintain their composure is a testament to his remarkable fortitude."

Randy Wilson said his father was very isolated during the trial. He often turned to the pastor of the Signal Mountain Methodist Church as the trial ground on.

"In those days, that had to be a pretty lonely job," said the younger Wilson, who is an attorney at Miller and Martin just across M.L. King Boulevard from his father's courtroom. "He was the only federal judge [in Chattanooga]. So the only person at work he could talk to was a law clerk, who was just one or two years out of law school.

"So, the only person I think he really felt like he could talk to and confide in was his pastor."

A VERDICT IS REACHED

The trial lasted from Jan. 20 to March 12, 1964, and remained the longest trial in Chattanooga history for decades.

Key testimony against Hoffa came from Teamster official Ed Partin, who testified to being paid $20,000 to rig the jury in the Nashville trial.

"When they were getting ready to announce the verdict or perhaps the sentencing, Teamsters truck drivers circled the block around the courthouse to show their support for Hoffa," Nicely said.

Hoffa was convicted of four of the 20 counts against him and sentenced to eight years in jail.

After the trial, Hoffa's attorneys filed multiple appeals to get the conviction overturned, including allegedly paying others to testify that federal prosecutors had provided alcohol to jurors, and later several local prostitutes accused the prosecutors of sending women to the jurors.

However, those efforts fell flat, as did attempts to implicate Judge Wilson.

"He was such a man of high morals, such high respect, and frankly such a good Christian man," Nicely said. "The minute they brought Judge Wilson into it, they knew it was a lie."

Randy Wilson said integrity and character were of paramount importance to his father, quoting his dad as saying, "Integrity is the virtue by which all other virtues are measured."

Frank Wilson died in 1982 at 65. He always said the strain of the Hoffa trial took 10 years off his life, according to Nicely.

Randy Wilson remembered his father was a fair jurist who managed to see the humanity and potential of everyone who came before him in court.

"Ultimately over his career he wrote thousands of letters to prisoners," Randy Wilson said. "If they would respond to him, he would stay in touch with them. Until my mother died, we used to get Christmas cards from some of his prisoners he had sent to prison."

"He would always encourage them to get an education and make better, and some of them did."

HOFFA DISAPPEARS

Hoffa appealed his Chattanooga conviction all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, but he was sent to prison in 1967, ending his reign as head of the Teamsters.

In 1972, he was released from prison early by President Richard Nixon and was attempting to regain control of the union when he disappeared in 1975, almost certainly assassinated, although his body has never been found.

Since 1998, Hoffa's son, James P. Hoffa, has been president of the Teamsters.

Frederick M. Shobe, ex-convict from Detroit, far left, leads the way to Federal Court for Teamsters president William Bufalino and Teamsters president James Hoffa, in Chattanooga, Tenn., Feb. 20, 1964. Judge Frank Wilson agreed to let Shobe tell the jury of an alleged conversation with a Nashville policeman who testified for the government. Yesterday Shobe told the court that he had been hired by the government to harass Mr. Hoffa. (AP Photo)

Frederick M. Shobe, ex-convict from Detroit, far left, leads the way to Federal Court for Teamsters president William Bufalino and Teamsters president James Hoffa, in Chattanooga, Tenn., Feb. 20, 1964. Judge Frank Wilson agreed to let Shobe tell the jury of an alleged conversation with a Nashville policeman who testified for the government. Yesterday Shobe told the court that he had been hired by the government to harass Mr. Hoffa. (AP Photo)Nicely said Chattanooga's role in the Jimmy Hoffa story has been largely overlooked in movies such as "The Irishman," and many visitors and residents don't realize Hoffa's connection to Chattanooga. But he said the events that happened in Judge Frank Wilson's courtroom in 1964 are a defining point in the story of the notorious union leader.

"I have always said that you can draw a straight line back from Hoffa's disappearance in 1975 to his conviction a decade earlier at the courthouse in Chattanooga," Nicely said. "It's what started in motion the removal of Hoffa from power.

"It was the beginning of the end and was what set in motion his assassination."

Contact Jim Tanner at JFTanner@gmail.com. Follow him at twitter.com/JFTanner.