NASHVILLE - A Tennessee legislative bill that proponents say would have blocked pharmacy benefit managers from reaping financial benefits from a federal drug-pricing discount program intended to help nonprofit hospitals and health centers serving low-income communities is dead for the year.

Members of the Senate Commerce and Labor Committee voted 6-2 to ship Senate Bill 1942 off to "summer study," effectively killing the bill. That came despite the opposition of Senate Finance Committee Chairman Bo Watson, R-Hixson, who voted against the move.

The legislation was aimed at protecting nonprofit providers serving the poor and uninsured that utilize the federal government's 340B Drug Pricing Program, a list that includes rural hospitals and community health centers, from discriminatory reimbursement practices that critics say are commonly employed by pharmacy benefit managers.

The 340B program enables covered entities to stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services. According to the federal Health Resources & Services Administration.

Bill sponsors Rep. Esther Helton, R-East Ridge, and Sen. Richard Briggs, R-Knoxville, issued a joint statement saying they were "dismayed."

"The bill was written to safeguard revenues that rural hospitals and community health providers depend on to provide services to thousands of vulnerable Tennesseans," Helton and Briggs said. "Without the protections afforded by this legislation, these badly needed dollars remain vulnerable to capture by private entities seeking to add to their own bottom lines."

Among nonprofit providers expected to take a wallop as result is Chattanooga-based Cempa Community Care, which provides infectious disease treatment and affordable care with comprehensive support services.

"I, like many healthcare leaders across the state, am discouraged by the Commerce & Labor Committee's decision to halt the progress of this immensely valuable bill," reads a statement by Cempa CEO Shannon Stephenson. "Our goal was to join other states in attaining protections from predatory [pharmacy benefit management] reimbursement practices aimed at capturing badly needed dollars originally intended to provide care for our most vulnerable friends and neighbors across the state."

Without such protections, Stephenson warned, "corporate middlemen remain able to siphon off revenue designed to provide care for patients across the state. Though our efforts have been thwarted in 2020, I fully anticipate working with the Tennessee Legislature in 2021 to gain passage of this bill."

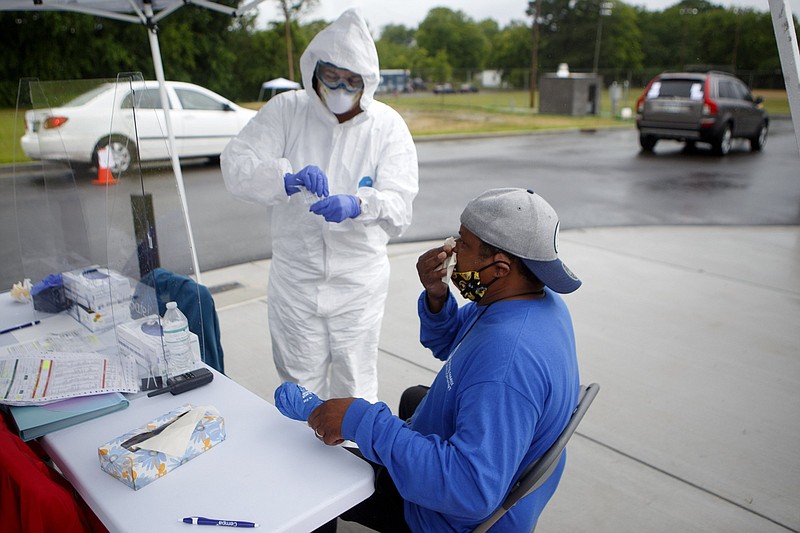

Cempa has been an active partner in Chattanooga's battle against the COVID-19 pandemic, rolling out "pop-up" testing centers in the city.

As lawmakers returned to the state Capitol on June 1 following a recess, Helton, a nurse, had stressed the need for the legislation. She and Briggs said they'd like the bill to be reintroduced next year in the new 112th General Assembly.

Pharmacy benefit management companies, which are either owned or work on behalf of insurance companies, successfully lobbied against the bill.

The 30-year-old drug discount program enables about 600 qualified providers in Tennessee to stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, according to Helton and Briggs, allowing them to reach more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.

But the lawmakers say that with the entry of pharmacy benefit managers, which negotiate drug prices, into the health care industry, many 340B providers are given "discriminatory contracts that absorb all or part of discount savings by reducing reimbursements or adding fees."

Helton and Briggs say providers in the 340B program often feel they have no choice but to sign the contracts because they're smaller with fewer resources and less bargaining power.

Contact Andy Sher at asher@timesfreepress.com or 615-255-0550. Follow him on Twitter @AndySher1.