While much of the attention fixates on hospital preparations, primary care providers on the frontlines are already in a full blown war against COVID-19.

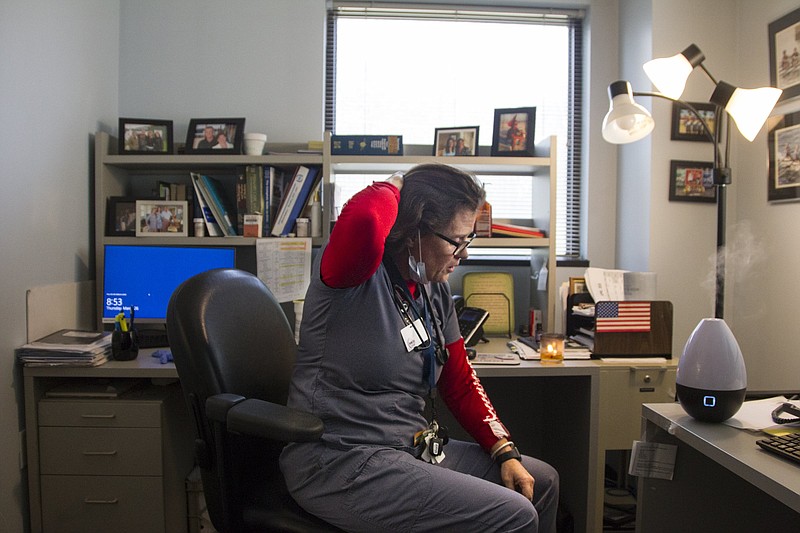

In just a few weeks, physicians such as Dr. Siobhan Duff have changed their entire practice - and lives - in the face of the pandemic.

Duff, a member of Chattanooga Family Practice, said three weeks ago she wasn't much different than the average citizen.

"We were kind of just living our normal lives, and then when the case announcement happened in Hamilton County, it was sort of like the light bulb went on. We were all deer in the headlights," Duff, who specializes in family medicine, said about the county's first COVID-19 case made public on March 13.

Family medicine doctors are often the first point of contact, serving as a gatekeeper between patients and the hospitals. They treat patients ranging from newborns to geriatrics and everything in between, getting to know patients and helping them navigate both their lives and health care needs.

COVID-19 is a new, fast-spreading disease forcing health care providers to radically change how they practice medicine in a short period of time. While some providers deemed "non-essential" wait for their chance to return to work, others such as Duff are rapidly scaling up to meet the demand of COVID-19 patients on top of safely continuing to provide routine care. She equates going to work nowadays with going to war.

"I can't think of any other way to think of this. We are the soldiers. The testing is the military intelligence for containment to the enemy, and the PPE is the armament and the weapons," Duff said. But a limited capacity to test patients and scarce supply of PPE, or personal protective equipment, makes the task more dangerous.

As of Tuesday, Tennessee and Georgia reported 6,058 confirmed COVID-19 cases combined, but Duff said an inability to test more patients means that's a gross under-representation of how many cases are actually in the community.

"I was told there was 1,900 [tests] in the queue at some lab," Duff said. "I'm not aware of a test turnaround that's any better than four to six days. I can swab all day long, and then have to apply the patient to a 14-day quarantine for a test that will never get run. So there are really, really tough ethical implications."

Often, the best and only recommendation she can give for a suspected coronavirus patient is self isolation. And without knowing how many people are infected, providers who may not have appropriate PPE must assume that everyone is COVID-19 positive.

"That has been the overriding cry of concern from people, and I communicate with literally hundreds of people through social media and through personal contact, not to mention patients. Many of my patients are also providers in the community, and they are literally terrified that we are being sent into battle without armor," she said.

For providers, COVID-19 is uncharted territory. Duff said many of her patients have been with her for more than 20 years, with a majority falling into the over-60 age range that's most at risk for serious illness and death due to the virus.

"In a word, we've militarized and we re-upped our entire office," she said of the nearly overnight transition to shifting all appointments from in-person to virtual. "I really have to give kudos to my nurses who are the ones who actually educate the patients - I had an 85-year-old woman today that managed to get herself on telemedicine with me alone in her house. So it's been a feat, and we're tired."

The practice conducted its first telemedicine visit March 20 and shifted to 100% telemedicine for all patients and providers by March 25 to limit opportunity for exposure. As of Monday, they had conducted 30 outdoor labs in a triage tent and 21,000 telemedicine encounters. Most of the screenings have been routine stuff, such as blood sugar checks, but Duff said she expects the volume of coronavirus-related screening and concerned calls to explode by the week's end.

Dr. James Haynes, a family medicine specialist at UT Family Practice and president of the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Medical Society, said some of the biggest challenges thus far have been changing the way he practices by shifting the mindset from patient to community care and making sure everyone's on the same page. His practice quickly ramped up telehealth and is heavily promoting social distancing and educating around what "shelter in place" means.

"It's a change for us not laying hands on our patients. We certainly will if we need to, but the reality is we can still do a lot of good medicine, make a good diagnosis with a good history," Haynes said. "We're just trying to keep people from each other - physical distancing with our abilities to communicate via new media. Social distancing is somewhat of a misnomer. It's about physical distance, not necessarily social distance."

While protecting herself, her family and coworkers, Duff works to educate patients and guide them through their range of emotions - anxiety, fear and sometimes indifference. She finds it most disturbing when misinformation leads people to call COVID-19 a "political hoax" or "government ploy." She said everyone needs to buy in to social distancing in order for it to work and stop the spread of the virus.

"If people are given the right information, they'll do the right thing 99% of the time. They are scared to death that this paycheck is going to be their last," Duff said.

She feels an extreme sense of urgency to educate the public before it's too late, looking at Italy as an example of how bad things can get when social distancing isn't taken seriously early.

"Because once you have 7,000 cases that have already infected 10 people per case, and then they go on to infect 10 more, it doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out how much community disease is out there now," Duff said.

She's also frightened by the complacency among some physicians, since she's noticed a lot of primary care facilities are still doing mostly face-to-face interactions with patients. She worries that doctors are contributing to the spread.

"People are so dialed in on their inpatient presence that they're not realizing they're creating petri dishes in the outpatient setting," Duff said. "When COVID hits, there's going to be people having heart attacks, strokes, babies, and if the entire medical profession goes down because we haven't protected ourselves, we're not going to be there when we're needed most."

When she returns home for the day, Duff leaves her clothes and shoes outside the door and heads straight to the shower to disinfect herself.

"My car is now designated as the COVID car. I don't let the kids ride in it, because I have stethoscopes and, you know, durable plastics and things that come out of the office," she said. "I have taken extra measures to ensure safety of myself, my family and my patients, because I'm a human vector walking in and out the door every day."

Haynes is taking similar precautions, including sleeping in a different bedroom than his wife and limiting contact with his 80-year-old mother-in-law who lives in the same home.

"We're all somewhat fearful, but we also have a duty to our patients and our community," he said. "That's what we signed up for."

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.