It started out normal, just like any year - just as normal as 2020.

American soldiers were serving overseas as World War I trudged into its fourth year, and then-President Woodrow Wilson was in the seventh year of his two-term presidency. A deadly virus that would soon bloom into a pandemic quietly loomed even for the president himself.

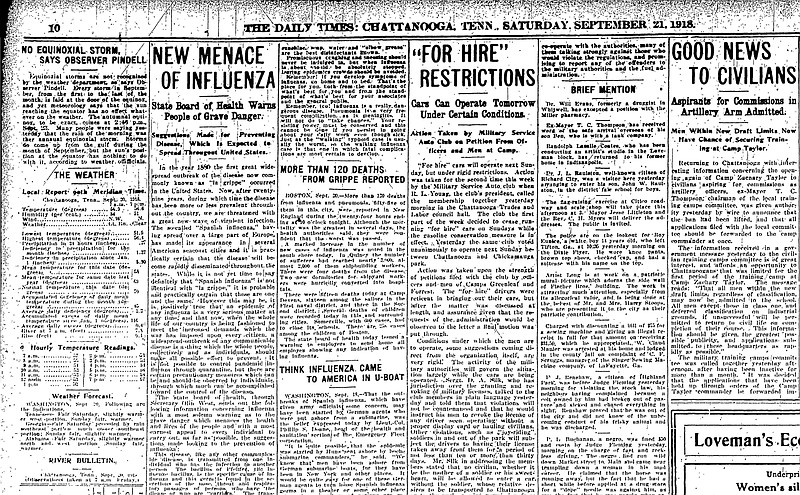

The year was 1918 and an influenza virus - that for the next century and afterward would be known as the Spanish flu - was first identified in military personnel that spring, according to historical information housed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. People a century ago often referred to influenza as "la grippe" or simply "grippe."

In less than two years, the virus would claim an estimated 500 million lives worldwide, as many as 675,000 of those deaths in the United States. The Spanish influenza was unique for a high mortality rate in people younger than 5, those between 20 and 40 and people 65 years and older, according to the CDC.

The flu's origin was unknown. It spread through North America, Europe and Asia in three waves in 1918-1919. In the U.S., the spring wave was relatively mild but the virus made a savage return in the fall of that same year.

(READ MORE: Coronavirus tracker for information on COVID-19 in Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama)

EAST COAST BEGINNINGS

In Chattanooga, some of the earliest reports in The Daily Times on the virus in the U.S. seem to stem from news of a Norwegian vessel that landed in New York in August 1918 with nine sailors aboard suffering from suspected Spanish influenza. The nine sailors were taken back to a hospital in Norway, where some were reported to be "very ill" while others "had passed the crisis and were on the way to recovery."

Two days later, the illness among the sailors was discounted as "an outbreak of pneumonia."

People were warned in a New York recommendation about the safety procedures for kissing in an article the next day.

"Persons who wish to avoid the Spanish influenza or the common garden variety of the same disease, were warned by the New York city department of health today not to kiss except through a handkerchief."

By Sept. 12, 1918, "Spanish influenza makes appearance along coast" was the headline announcing the feared ailment "which recently ravaged the German army and later spread into France and England with such discomforting effects on the civil population, has been brought to some of the American Atlantic coast cities, officials here fear, but they are awaiting further investigation and developments before forming definite opinions."

Officials, the story said, believed the virus was brought in through American transports returning to the U.S.

(READ MORE: Soddy-Daisy woman survived Spanish flu pandemic of 1918)

"There is little means of combating the disease except by absolute quarantine, and that obviously is impossible because it would require interruption of intercourse between communities as was resorted to in the dreaded days of yellow fever in the south," the story reads, recalling the epidemics of yellow fever in the 1800s and earlier.

In a story a day later, U.S. Surgeon-General Rupert Blue offered instructions to doctors on "How to Treat New Grippe," referring to the Spanish influenza virus that was raging in American seaports. Blue said a survey was being taken to determine the extent of the Spanish flu's domestic spread.

Blue "has found a sharp outbreak at Fort Morgan, near Mobile, Ala., in August, and about the same time a tramp steamer arrived at Newport News with almost the entire crew prostrated," the story reads.

Blue gave a grisly description of the symptoms and immediate measures to take that sound familiar as the 2020 world battles the coronavirus.

"The disease is characterized by sudden onset," Blue told the Associated Press on Sept. 13, 1918. "People are stricken on the streets, while at work in factories, shipyards, offices or elsewhere. First, there is a chill, then fever, with temperature from 101 to 103, headache, backache, reddening and running of the eyes, pains and aches all over the body and general prostration. Persons so attacked should go to their homes at once, get to bed without delay and immediately call a physician."

Blue's recommended treatment was bed rest, fresh air, plentiful nourishment and "Dover's" powder, a cold and fever remedy containing opium, to reduce pain.

The story noted the lack of experience among doctors of the day.

"Because the last pandemic of influenza occurred more than twenty-five years ago physicians who began to practice medicine since 1892 have not had personal experience in handling a situation now spread throughout a considerable part of the foreign world and already appearing in the United States."

Why the “Spanish” flu?

The 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic didn’t originate in Spain as the name would seem to suggest, according to information on history.com. As the pandemic reached its peak in the fall of 1918, it became commonly known as the “Spanish Flu” or the “Spanish Lady” in the U.S. and Europe. The nickname was actually the result of a widespread misunderstanding because, Spain, as one of only a few major European countries to remain neutral during World War I, had media that wasn’t constricted by wartime censors so reports from the neutral country were far more revealing. News of the virus first appeared in Madrid in late-May 1918, and coverage only increased after the Spanish King Alfonso XIII came down with a bad case a week later. People in nations that were under a media blackout for the war could only read in-depth accounts from Spanish news sources, so they assumed that the country “was the pandemic’s ground zero,” history.com states. The Spanish, meanwhile, believed the virus had spread to them from France, so they took to calling it the “French Flu.”

ARRIVAL IN TENNESSEE

A Chattanooga doctor in the next days warned local people to be on the lookout although the dreaded virus hadn't been identified in the city yet. A story noting the death toll at the Great Lakes naval training installation in Chicago was believed to be around 500, said "physicians stress the probability that the disease will be brought to Chattanooga through the cantonment or by visitors from the coast towns."

People were told to go to the doctor immediately "upon the appearance of alarming symptoms." The danger of the new flu virus was its tendency to develop into pneumonia, which could prove deadly.

As September wore on, there were more reports from Chicago, New York and Massachusetts about the spread. In one story, 12 tips from the U.S. Army's surgeon general were offered to "avoid the ravages of Spanish influenza" which included avoiding crowds, "smothering" coughs, and one admonishment, "your nose, not your mouth, was made to breathe through - get the habit."

People were told to remember the three Cs; clean mouth, clean skin and clean clothes; to try to keep cool and open windows at home at night; eat well and chew food thoroughly; and to wash hands before eating. The tips also said not to share eating utensils, cups, glasses, napkins or towels.

There were also some odd recommendations at the end of the list but maybe they were helpful. "Avoid tight clothes, tight shoes, tight gloves - seek to make nature your ally, not your prisoner," the 11th directive from the U.S. Surgeon-General of the Army William C. Gorgas states, and No. 12, "When the air is pure breathe all of it you can - breathe deeply."

People in the Chattanooga region seemed to be holding their breath instead.

In early October, Spanish influenza cases started to appear in Tennessee. Schools in Johnson City, Tennessee, were shut down after four teachers came down with the virus and as much as 50 percent of the student population was out sick, reports state.

At Camp Greenleaf just over the state line in Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia - where military officers were temporarily training for medical work - there were 13 deaths over three days all blamed on complications of pneumonia, newspaper reports state. Nationally, more than 14,000 new cases had been tallied in a 24-hour period generating 88,000 Spanish influenza cases, more than 6,700 cases of pneumonia and leaving 1,877 dead.

VIRUS HITS CHATTANOOGA

On Oct. 5, a headline struck a local cord - "Grippe hits Chattanooga" - as 500 cases of flu were reported by Chattanooga's leading doctors.

"Most of the physicians say they are not certain whether it is Spanish influenza or the old-fashioned grip, such as spread over the country in a similar wave about twenty-seven years ago, for it is hard to differentiate," the story states, noting the general belief that the Spanish flu had a tendency to develop into pneumonia.

"All the doctors are agreed that whatever it is, the symptoms of the various cases in Chattanooga are practically the same, beginning with a severe headache, high temperature, sore throat and affection of the bronchial tubes, coughing and general soreness and aching of muscles and joints," the story continues.

"Dr. E.B. Wise, city physician, compared this epidemic of influenza with that of about twenty-seven years ago and said seemed very similar to him, except that the former epidemic seemed a little more restricted to the aged, and this is more general in its sweep."

A "combined vaccine or serum" was administered to Chattanooga patients but there was no certainty the treatment was a cure, "but it can do no harm, is cheap, and in some cases it seems to be doing a great deal of good."

Chattanoogans were warned against "undue fright if you are stricken," because fatalities were said to be comparatively few. Local physicians reportedly differed on whether the local illness was the "real" Spanish flu or just a regular flu. Officials ordered theaters closed and a call was issued by the Fort Oglethorpe Red Cross Auxiliary for volunteers to make 1,000 masks for the public. Methods were offered for making masks at home.

Society pages became filled with flu-related entries on Oct. 9. Lucy Ray Milburn was sick with influenza at her home in St. Elmo, and Mr. and Mrs. Hardy Johnston of Cleveland were at the Park Hotel where Mr. Johnston was ill with the flu. Alongside those entries was a report that then-Tennessee Gov. Tom C. Rye had the flu and a nominee to the state Legislature, R.P. Craig of Centerville, had died of the virus.

The virus notched a local headline when Walter C. Wells, a well-known 28-year-old Chattanooga bricklayer who attended Baylor and McCallie, died.

On Oct. 10, it was estimated that between 9,000 and 12,000 cases were active at that time, and there were calls for volunteers to help with flu victims. On Oct. 13, health officials said 12 people in Chattanooga had died of the flu the day before and the peak of the virus impact would come the next day. Some physicians believe the flu was striking one in 10 Chattanoogans and everyone was advised to wear a mask.

As October wheezed toward winter, more sick and dead flu victims were listed in the pages of The Daily Times and other newspapers, churches halted services, meetings were canceled, homes became temporary infirmaries.

Then by mid-October, officials were beginning to see case numbers go down.

A DECLINE AT LAST

At the same time, people began to demand that schools - closed due to the virus - be reopened, but no plans for that were even being considered yet.

On Oct. 22, the headline "Sees an end of epidemic" heralded the decline in cases at Camp Greenleaf but even as it declined the news still sometimes was tragic. On Oct. 23, Charles Patterson, 8, died at a facility at Bonny Oaks. Of 54 cases said to be at the facility, the boy's death was the only fatality there.

By the end of October, business was getting back to normal in Chattanooga. Atlanta was reportedly opening up, churches and school systems were beginning to reopen. In late November 1918, influenza reappeared in local schools but Chattanooga doctors determined it was the "old-fashioned" type and no cases of pneumonia were arising as a complication.

According to a Dec. 5, 1918, article in The Daily News, an estimated 300,000 Americans had died of Spanish flu since Sept. 15 of that year. By the end of the Spanish flu pandemic in 1920 that number would more than double.

Contact Ben Benton at bbenton@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6569. Follow him on Twitter @BenBenton or at www.facebook.com/benbenton1.