For months, Karen Collins felt like she was living a double life. She spent nearly every day of the week working to get people in Chattanooga vaccinated, especially people of color, and fighting the rampant misinformation around the vaccine.

But, in her own family, she struggled to convince her adult children to take a dose.

"I was very angry," Collins said. "I was sad. I was scared. I was full of rage at times because I know this is a tool, by that I mean vaccinations, by which we can help our community and you're going to tell me that you're not? You're just not?"

She finally had some luck late last month, as a surge in the coronavirus driven by the delta variant seems to be convincing more people to get the shot.

Last week, the 12-county region surrounding Hamilton that includes Bledsoe, Bradley, Coffee, Franklin, Grundy, Marion, McMinn, Meigs, Polk, Rhea and Sequatchie counties was averaging more than 940 first-dose shots a day over a seven-day period, according to data from the Tennessee Department of Health. During the first week of July, the seven-day average for the same area was fewer than 300 first-dose shots a day.

Collins had faced a year of hardship at the hands of the virus. The shutdown delayed her wedding. In December, her then-fiance got sick and spent months in the hospital fighting for his life. Collins was told multiple times to get things in order for his death, she said, but he survived.

Her 22-year-old son got sick with the virus while at college in Ohio. Her 21-year-old daughter was infected too, but had only mild symptoms.

Collins, who works for the city, dedicated herself in 2020 to addressing disparities in COVID-19 testing. When the vaccine arrived in Hamilton County, she worked to make sure the rollout was equitable and accessible for all communities.

Her adult children thought because they had gotten sick before they did not need a vaccine. They were hearing misinformation or conflicting information on social media, Collins said. Her son had not been vaccinated. Her daughter received the first dose but had not gotten the required second shot.

Collins tried to fight back, providing them the same science-based material she was helping spread in the community.

The family standoff lasted for months. Collins recognized her children as adults, but she was still their mother.

"I'd rather know that I had done everything that I could have done in order to keep them alive than to not try and have something happen to them," she said. "I could've easily said they're grown, they make their own decisions, I'm not going to be forcing them, blah blah blah, but I know the kind of person I am and the kind of mother I am, I couldn't live with myself if I hadn't done everything that I could to empower them or support them."

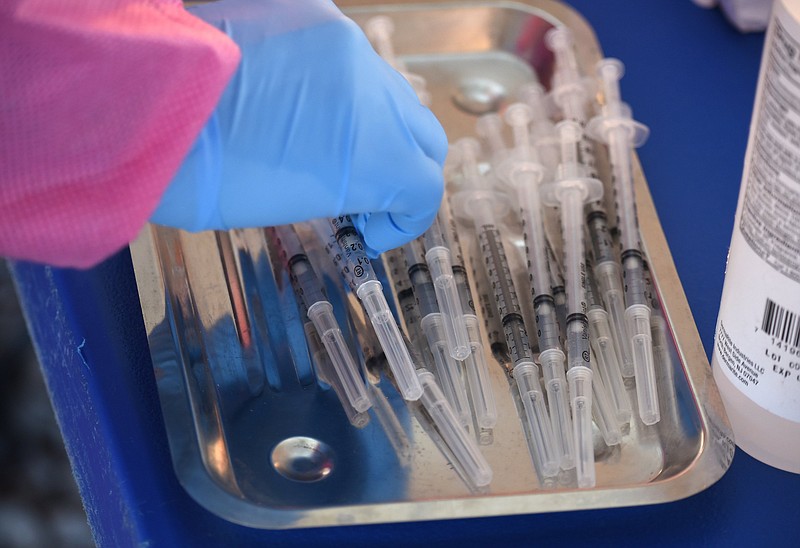

On July 31, Collins took her two children to a community vaccination event in East Lake. The car ride was tense but the atmosphere at the event was comfortable, Collins said. Elected officials were there. Pastors were there. Medical professionals were on hand to address concerns, she said.

(READ MORE: First-dose vaccination rates for COVID-19 are again rising in Southeast Tennessee)

When her son got his vaccination card, Collins held onto it like it was a birth certificate. She recognizes her children could still get sick with the virus but the effectiveness of the vaccines means they are extremely unlikely to be hospitalized or die from the virus, a threat that disproportionately affected communities of color.

MORE VACCINATIONS

Between July 1 and Aug. 1, Hispanic residents had the greatest increases in vaccinations among racial or ethnic groups in Hamilton County. The number of Hispanic residents who received a vaccination increased by nearly 10%, along with an 8% increase in the number of Black residents vaccinated. The population of white residents vaccinated increased by 4.7% over the same time period, according to state data.

As of Thursday, 32% of Black residents in the county were at least partially vaccinated compared to 41% of white residents and 42% of Hispanic residents. Asian residents account for the racial or ethnic group in the county with the highest percentage of the population at least partially vaccinated with 53%, according to data from the Hamilton County Health Department.

The youngest eligible residents in Hamilton County have driven the overall increase in vaccinations in recent months. Between July 1 and Aug. 1, residents ages 10 to 19 accounted for around 1 in 5 new doses administered in Hamilton County, according to data from the Tennessee Department of Health.

"The good news is vaccinations are also up a little bit but they're not up to the rate or to the nature that they need to be to blunt this surge that's coming, that we're in the midst of," Becky Barnes, administrator of the Hamilton County Health Department, said Wednesday during a county commission meeting.

The county set recent records for new cases and hospitalizations with case rates and hospitalizations unseen since the winter surge that killed a record number of people.

Local health officials have said the vast majority of hospitalizations and deaths in Hamilton County in recent weeks are among unvaccinated individuals. Nearly half of the hospitalizations reported Thursday were Hamilton County residents, with the rest from the surrounding area.

County commissioners and the county mayor raised concerns about a lack of hospital capacity this week as local health providers struggle with staffing shortages caused by pandemic-related burnout.

During the Wednesday commission meeting, Commissioner Tim Boyd said there is no excuse not to get vaccinated. The education on vaccine safety is available, he said, and people are dying because they are not getting a dose.

"These are not abstract numbers. These are real numbers," Boyd said.

CONCERNS OF THE UNVACCINATED

A survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation of American attitudes about the COVID-19 vaccine, released Wednesday, found that while seven in 10 adults say they have gotten their vaccine or plan to do so soon, around 14% of American adults will "definitely not" get a vaccine, a percentage that has largely remained steady since the surveys began in December 2020.

Of those surveyed, the population groups with the largest percentage of respondents saying they would "definitely not" get vaccinated were uninsured and under age 65, white evangelical Christians, rural residents and Americans between 18 and 29.

Those who told the Kaiser Family Foundation they would "definitely not" get the vaccine said overwhelmingly that they believe the risk of the vaccine was greater than the risk of being infected with COVID-19.

The three available vaccines - Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson - were rigorously tested for safety before they were approved for emergency use in the U.S. and continue to be monitored for safety. More than 346 million doses of the vaccines have been administered, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Historically, vaccine side effects generally appear within six weeks of a dose, according to the CDC, and side effects from the vaccines are very rare.

Dr. Matthew Kodsi, vice president of medical affairs at CHI Memorial, has been assisting with the local vaccination effort since Feb. 15, working to convince hesitant Chattanoogans of the need to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Though individuals vary in their concerns and reasons for not wanting to get vaccinated, Kodsi said people typically fall under one of the following categories: those who wanted the vaccine and already received it, those who are not able to be swayed no matter how much positive information and evidence they are presented, and those who are open to the idea but afraid.

Kodsi is focusing his attention on the "hesitant but afraid" group. Those individuals have concerns, he said, and trying to scare them into getting the vaccine is not an effective strategy because they are already more afraid of the vaccines than the virus.

(READ MORE: Unsure about COVID-19 vaccine safety? Here's what the science says.)

The doctor takes the time to have one-on-one conversations to learn about each individual's concerns and what is important to them.

"What we want is for people to really understand all the information about the vaccine, and all the implications and repercussions of their choice, so that they can truly make that informed choice," Kodsi said. "Because informed doesn't just mean, 'I know how the vaccine works.' It means, 'Do I know what's gonna happen when I take the vaccine? Do I know how much the vaccines can protect me? Do I know what it means for society if I don't take the vaccine?' They have to understand that the choice they make obviously affects them, but it doesn't just affect them, it affects everyone."

Some of the most common concerns he hears are the perceptions that the vaccines were made too fast and have not been around long enough. Other common ones include the misconception that the vaccines will make people infertile or sick. Through tens of thousands of clinical trials and hundreds of millions of doses administered, side effects are extremely rare. And while the vaccines themselves are new, the scientific technology that makes them effective has been studied and used for decades.

"And then there's just the general, 'Ah, you hear all these bad things on the internet about the vaccine,'" Kodsi said. "We let social media go rampant, and now we're playing catch-up."

On Wednesday, Commissioner Warren Mackey asked Barnes about the ongoing spread of misinformation about the virus. Barnes said the county health department is still being accused of making up the pandemic and the statistics, including the deaths of county residents.

"Why that persistent denial of reality?" Mackey asked Barnes.

"I don't know," Barnes replied. "I guess, if we knew and if we really understood what that was or how to fix it, we would as a country. But I don't know."

Staff writer Elizabeth Fite contributed to this report.

Contact Wyatt Massey at wmassey @timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6249. Follow him on Twitter @news4mass.