COVID-19 vaccines were never promised to be 100% effective, and experts are united in saying they remain the best way to combat the pandemic.

But a growing number of breakthrough cases - the term used to describe people who become infected by the coronavirus despite being fully vaccinated - is drawing attention to how much research is still needed to better understand the virus.

Breakthrough infections were thrust further into the spotlight this past week as more high-profile, fully vaccinated individuals across the nation - including Chattanooga Mayor Tim Kelly - announced they had tested positive for COVID-19. Kelly, 54, tweeted Wednesday that he had "mild, allergy-like symptoms" thanks to the vaccine preventing a more serious case.

"We knew we were going to see these breakthrough infections, but the important thing is to look at what's happening to these people," said Dr. Jensen Hyde, a hospitalist at Erlanger Medical Center who also holds a master's degree in public health. "We have people who have breakthrough infections that are very, very high risk for hospitalization and death, and now they might get the sniffles or be asymptomatic."

According to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, there's a difference between "breakthrough infections," which occur when a fully vaccinated person tests positive for the coronavirus and "breakthrough disease," which occurs when a fully vaccinated person experiences symptoms of COVID-19.

That distinction is important when discussing the effectiveness of vaccines because Johnson & Johnson is currently the only drug company with a COVID-19 vaccine available in the United States to use a positive test result plus the presence of one symptom as its criteria for assessing vaccine efficacy. Both the trials for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which boasted about 95% efficacy against the original coronavirus variant, studied whether the vaccines prevented COVID-19 symptoms, not infection.

Despite the growing prevalence of vaccinated people testing positive for the coronavirus, the vast majority of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths continue to be in the unvaccinated - a strong signal that the vaccines are doing a great job protecting against the most serious forms of disease, said Dr. Carlos Baleeiro, a pulmonologist and critical care specialist at CHI Memorial Hospital.

"Breakthrough doesn't mean that the vaccine failed. It means the vaccine has a rate of success, and some people may still get a symptomatic infection," Baleeiro said, adding that vaccine efficacy was expected to decline as the virus mutates into new variants, such as the now-predominant delta variant.

"If you look at total efficacy against delta, it goes down compared to the efficacy against earlier variants, but if you look at prevention of severe infections and death, it is still very, very good," he said.

Data on breakthrough cases is limited, and tracking varies widely across states and localities, meaning much of the understanding of breakthrough infections comes from anecdotes.

The numbers fluctuate daily, but when Baleeiro checked the hospital's COVID-19 patient makeup last week, it was about 80% unvaccinated and 20% vaccinated. There were also no vaccinated patients in the intensive care unit, he said.

The vast majority of vaccinated patients who are hospitalized are also older, have a chronic condition that makes them more vulnerable or a weakened immune system, rendering all vaccines - not just one for COVID-19 - less effective.

"They may still have a more significant breakthrough infection, but they would be much more likely to have a worse outcome without the vaccine," Baleeiro said. "This is one small sample from one hospital, but the pattern is what we would expect."

Hyde described similar trends at Erlanger.

"I can only speak to my personal experience, but I have yet to have a vaccinated person in the ICU. I've had a handful on the floor, and they have all gone home," she said. "I have had a fully vaccinated 92-year-old I admitted that did better than an unvaccinated 30-year-old, so if that's not evidence of efficacy, I'm not sure what is."

Parkridge Health System declined to comment for this story.

Both Hyde and Baleeiro said there's a perception issue when it comes to breakthrough cases, and a major reason why they're becoming more common is because more than 170 million Americans are now fully vaccinated.

"As more people are vaccinated, everybody will know somebody who was vaccinated and has the disease, but that is not a failure of the vaccine. It's just mathematics," Baleeiro said. "Part of why people are posting or sharing, or why everybody knows a story of somebody who had the vaccine and who is now sick, is because that is less common When you see or hear of somebody who has breakthrough of the vaccine, that is something novel, and it attracts attention. It's more memorable."

Hyde said the high level of community spread combined with a low vaccination rate and a return to in-person activities without precautions are also contributing to the rise in breakthrough cases.

"Numerically, the number of COVID cases in the region is up thousands of percent from where it was in early June, so the number of COVID patients in the hospital, period, is exponentially higher than it was just a few weeks ago," she said. "You could have a single layer approach - meaning I'm fully vaccinated - if community spread is very low. If the spread is very high, then a multi-layer approach is going to be more effective, but you're still exponentially less likely to end up with COVID [when vaccinated]."

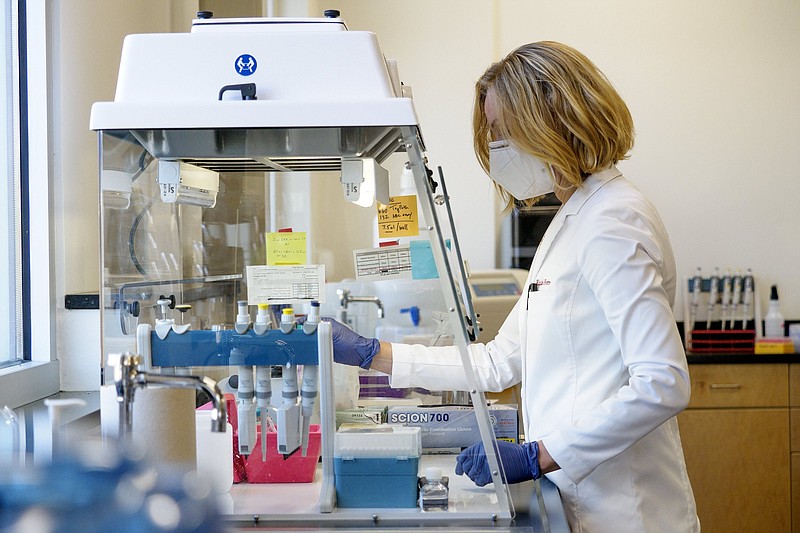

Elizabeth Forrester, technical director and co-founder at Athena Esoterix - formerly the Baylor Esoteric and Molecular Lab - said the lack of quality data on breakthrough infections is frustrating from a research standpoint.

On May 1, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stopped investigating breakthrough cases unless they resulted in hospitalization or death. That decision is now facing criticism from some experts who say scaling back those efforts is leaving researchers unable to answer important questions:

- When does immunity start waning for those who are vaccinated?

- Are new variants better able to evade vaccines?

- Are certain demographics more prone to breakthrough infections?

- Do breakthrough infections result in similar long-term effects as unvaccinated infections?

Identifying clusters of vaccine breakthroughs could also help identify manufacturing or storage and handling issues.

On the other hand, some say tracking an outcome that was expected is not the best use of finite public health resources.

The latest COVID-19 critical indicators report from the Tennessee Department of Health, dated Thursday, states that breakthrough cases account for 1.7% - or 16,296 of 977,230 - of the state's total confirmed cases, but that number is likely a significant undercount. Many of those who become infected post-vaccination will not be sick enough to notice or seek testing, and until recently, the CDC didn't recommend that vaccinated people be tested following exposure, according to Johns Hopkins.

Of Tennessee's 23,889 hospitalizations, 368 (1.5%) have occurred in fully vaccinated people, according to the critical indicators report. Meanwhile, 108 (0.8%) out of 13,142 total deaths have occurred in fully vaccinated people.

From May to July, 90% of confirmed cases, 88% of hospitalizations and 94% of COVID-19 deaths in the state were among the unvaccinated, according to the report, which also notes that the department "currently conducts more robust active surveillance for hospitalized COVID-19 cases that are vaccinated than for those that are unvaccinated; therefore the data for hospitalizations among the unvaccinated may be incomplete."

Early on in the vaccine rollout, Forrester's lab was heavily focused on trying to "sequence" the genetic makeup of breakthrough cases from positive COVID-19 samples that the lab processes from area providers. Sequencing is the laboratory technique that detects variants of the virus.

"But we weren't able to sequence them, which indicated that the viral load was so low that even though that one breakthrough for that individual happened, the chances of them transmitting the virus to others was really, really low, and all of that was tracking really well with what we expected to happen," Forrester said, adding that there's not a compelling reason to follow those cases.

Then the rapid rise of the delta variant threw a curveball. Forrester said test results for vaccine breakthroughs started to show viral loads as high as people who were unvaccinated. Similar findings in other areas of the country prompted the CDC to revise its face mask guidance to include vaccinated people again and begin advising people with certain immune-compromising conditions to seek booster shots. Starting in September, boosters will be recommended for fully vaccinated people who have gone at least eight months since their last dose.

"We need both masks and vaccines right now, and it's really disheartening and sad that we can't get that message across effectively," Forrester said. "This is happening in real time to all of us. People are like, 'The vaccines are failing.' They're not failing, the virus has changed. I think anyone that is in science and following this knew this was going to happen. It's just the speed at which this has happened has caught a lot of people off guard."

Hyde said transmission is complicated and viral load is just one of many contributing factors, and better data is needed before the medical community can fully understand a vaccinated person's ability to spread the disease. Because vaccinated people's immune systems know the virus, it will not be able to replicate as much in the body, she said.

"The period of infectiousness for somebody who's vaccinated is going to be much shorter than somebody who's unvaccinated, so saying vaccinated people are as likely to spread - even based off of that very limited data - is not an accurate statement," Hyde said, adding that getting more people vaccinated remains "the biggest piece of the puzzle."

"It's just not an option to be complacent in this anymore, and we in a lot of ways missed our window to prevent this wave," she said. "We are a very well-resourced country that has some of the most effective vaccines of the 21st century available, free of cost, and in our county 52% of people chose not to do that. And that's a big reason why we are where we are."

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or follow her on Twitter @ecfite.