The early weeks of 2021 carried a sense of promise for the Chattanooga health care workers who were weathering a devastating winter surge of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths. Vaccines were being administered. By late January, cases were dropping.

Gov. Bill Lee invited tourists to the state and even offered an incentive program for them to come. Hamilton County's mask mandate was lifted. Live music returned to downtown and the Riverfront on Friday and Saturday nights.

But three weeks in August erased the months of momentum as an exhausted and understaffed workforce now face a wave of sick patients that threatens to overwhelm the local and state health care systems.

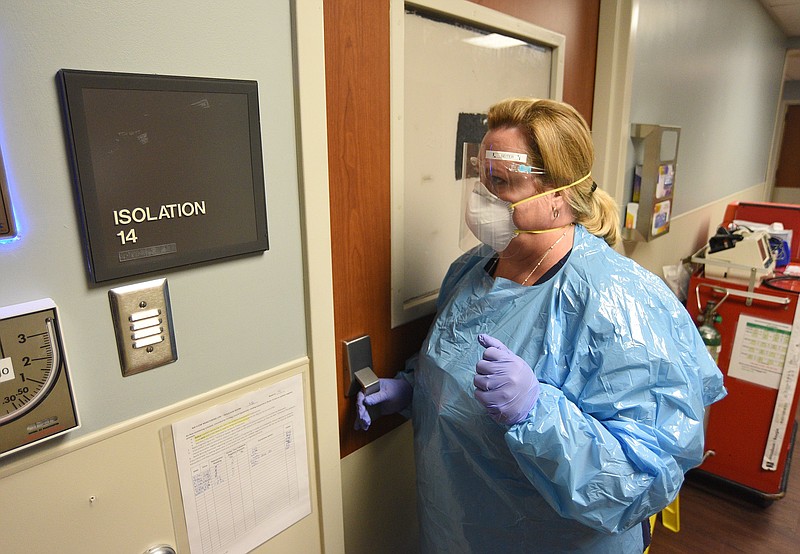

The treatment for Chattanooga's sickest patients largely resembles the previous peak, but as hospitalizations continue to break records, demoralized workers are haunted by one key difference.

This was preventable.

"We had the vaccine, and there was hope that we were going to be able to recover," said Chyela Rowe, a therapist who coordinates staff support services at CHI Memorial Hospital. Rowe was charged with "keeping a pulse" on how workers are holding up mentally throughout the pandemic.

"Then, to have the hospital fill up, and to have people dying from this virus and to know that it's preventable - it just hits people so hard. Our staff are genuinely grieving," she said.

Though COVID-19 vaccines provide strong protection against hospitalization and death, the majority of people in the Chattanooga region remain unvaccinated.

Intensive care unit nurse Rachel Ragan said she cried tears of joy when Erlanger Health System closed its COVID-19 unit in the spring.

"I just felt so much hope and relief. That had been the hardest time in my 16-year career as an ICU nurse. I thought we had made it," said Ragan, a clinical staff leader in Erlanger's medical ICU. "We got down to one [COVID-19] patient at Erlanger, and now we're busting at the seams - we're totally at max right now.

"I was just not prepared to do it again. And none of us were, really," she said.

Hamilton County's three hospital systems, CHI Memorial, Erlanger and Parkridge, on Friday housed 256 COVID-19 patients, including 78 in ICU - both record highs for the pandemic - according to data from the Hamilton County Health Department.

Regional hospital capacity to treat not only coronavirus patients but all other emergency medical needs, such as heart attack, stroke and trauma, was already dangerously low before the new peak on Friday.

On Thursday, the Tennessee Hospital Association posted its weekly data report, which states that hospitals in the Chattanooga district encompassing Hamilton, Bradley, Marion, Sequatchie and Van Buren counties had only 17 general adult beds available and six open ICU beds, a measure that takes into account staffing in addition to physical space.

Hospitals use a variety of methods to increase capacity, such as delaying non-emergency procedures, asking staff to work overtime, pulling staff from other departments, using travel nurses or diverting ambulance traffic to other facilities. But each of those options has a significant downside and may not be available when the entire region and much of the country also is overwhelmed by COVID-19.

Non-urgent procedures are the lifeblood of a hospital's revenue, and it's costly to pay staff overtime or bring in travel nurses. Unlike the early days of the pandemic, it's uncertain if hospitals will get any more federal relief funds to offset those costs.

Capacity can also fluctuate widely throughout the day. While severely ill coronavirus patients can occupy beds for weeks or even months, less-serious cases may only stay a day or two, and this is true for many other ailments that hospitals treat. But when beds are near their max, a car wreck or COVID-19 outbreak at a nursing home can be what tips the scale.

Staffing becomes particularly problematic for patients needing intensive care because they require more one-on-one attention and specially trained clinicians. Pre-pandemic studies show that the likelihood of medical errors increases when staff is stretched thin or employees are working outside their specialty.

In desperate times, clinicians can be forced to make tough ethical decisions, such as having to choose which patients get admitted, which stay in the emergency department and which get sent home to try and manage their condition as an outpatient.

"We want to take excellent, perfect care of everybody. But with the surge, some of our patients are not making it all the way to a patient room, just depending on what's going on," said Emily Seiter, nurse manager for the ER at Parkridge Medical Center. "Nurses always want to take the best care of their patients, and sometimes that is a problem when you have so many patients."

The nationwide nursing shortage - a longstanding issue for hospitals that was made worse by the pandemic - presents one of the biggest challenges in the current surge, Seiter said. Though Parkridge hasn't seen high nurse turnover like many other hospitals, she said the hospital did resort to using travel nurses.

(READ MORE: Resurging cases, patients' anger drive weary nurses from front lines)

Jenny Dillard, director of operations for emergency services and manager of CHI Memorial's main emergency department, said in an email that local hospitals are facing a shortage of all support services, not just nurses.

"Our ERs are overcrowded on a daily basis, and we're struggling to see patients who are experiencing long waits. We, as ER staff and physicians, are frustrated for our patients because of the long wait and are working tirelessly to find new ways to get patients seen as quickly as possible," Dillard said.

Aside from the availability of COVID-19 vaccines - which continue to provide strong protection against hospitalization and death because of the coronavirus - several factors set this latest peak apart from others. Patients this round are younger and sicker. Data from the Tennessee Department of Health shows that although the state hasn't yet exceeded its winter hospitalization peak, more patients are requiring intensive care and ventilators than before.

When patients are sicker, they are in the hospital longer and require more oxygen and other resources, which Dillard said are more scarce because of the high demand across the nation.

"We are seeing delays in things we've never had delays in before," she said, such as long shipping times for everyday items like cables and supplies for cardiac monitoring.

Most notable, though, is the rapid rise from hospitalization levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic to record-breaking patient volumes.

The previous peak was reached after months spent with patient volumes hovering in the mid-40s to mid-70s range before gradually climbing from 47 inpatients on Oct. 10 to 242 patients on Dec. 31.

On June 28, 11 COVID-19 patients were hospitalized in the county, and there's been a 23-fold increase since then to reach a new peak.

The highly contagious delta variant and an under-vaccinated, under-protected population are to blame, and the current patient surge is expected to continue for several more weeks.

Erlanger nurse Ragan is concerned about what the next month will look like.

"When I'm off work, I feel guilty, because I know how much we need more nurses. And we don't have enough nurses, so it just feels like this ton of bricks on my chest," Ragan said, adding that she's always worrying about her patients in addition to her coworkers.

"I'm texting the nurses who are there to check on my patients. They're in my constant thoughts and even in my dreams," she said. "I can't get the sound of their family members sobbing out of my head."

CHI Memorial therapist Rowe, who is currently conducting doctoral research on burnout in health care, said that "there's a different level of trauma" for staff that are at the bedside watching COVID-19 patients die.

"But every single department is suffering at the moment because everybody is participating in some way," she said.

Rowe said the two main factors that contribute to burnout in health care - which was an issue long before the pandemic - are lack of work-life balance and feeling like your work doesn't matter.

(READ MORE: Chattanooga doctor's new book aims to support, empower health care professionals)

"Those are the two things that have been stripped away, because of the staffing shortages, the increased demands, and then just the hopeless loss of life," she said. "You have a lot of clinical and medical staff that went into certain areas of medical practice where they weren't anticipating lots of loss of life. Right? They're anticipating being able to save lives, and that's just not been possible for a lot of people that get really intense cases of COVID."

Dillard said it's become "a constant challenge to maintain positivity for the work that came so naturally prior to the pandemic."

"The biggest challenge is caring for the emotional stress of frontline staff, patients and visitors. In our roles, we have to lead through difficult decisions that may not be viewed well by the public or our own teams. It is difficult trying to stay positive and motivated while we as leaders are struggling with our own emotional stress," she said.

Despite the struggle, Seiter wants the people to know that the emergency department always will be there to take care of them in the case of an emergency, but the best thing the public can do to help hospital staff is to prevent getting sick in the first place.

"We come in every day, and we're going to take care of the patients that come in, and everybody does the best they can," she said. "The big thing we want people to know is, it continues to be social distancing, handwashing, masks and getting vaccinated."

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or follow her on Twitter @ecfite.