A Chattanooga businessman was apparently gunned down at the order of former Tennessee Gov. Ray Blanton in an attempt to cover up his infamous "pay for parole" scheme, according to Hamilton County District Attorney Neal Pinkston.

Blanton's administration, a state trooper and other operators across the state ran a racket in the 1970s, infamously known as the "cash for clemency" or "pay for parole" scheme, in which the administration took payouts to commute sentences or pardon criminals.

When Operation TennPar, a federal investigation into Blanton's misdeeds that resulted in his ouster and the arrest of three of his aides, began in 1978, a much larger cover-up scandal began brewing, according to local authorities.

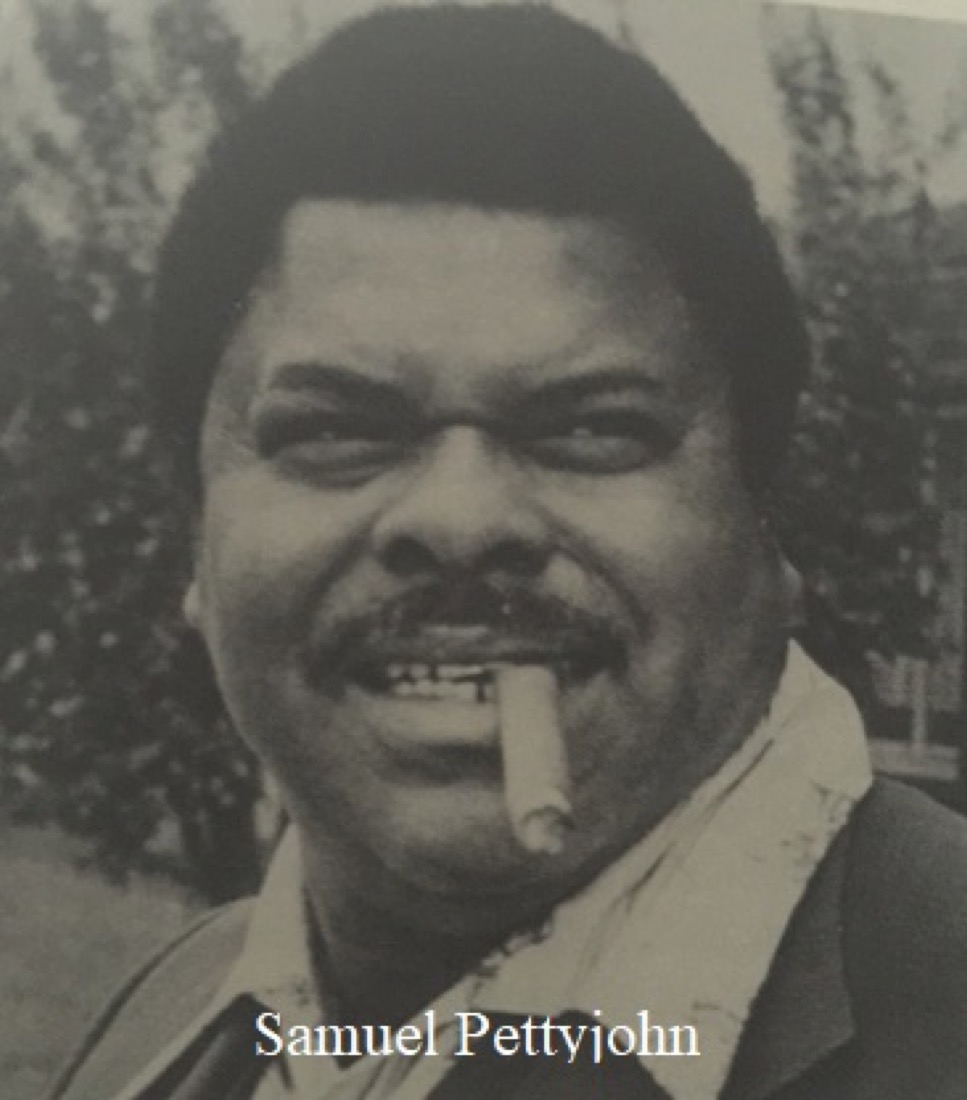

Pinkston's cold case unit said Wednesday it has linked the 1979 murder of Samuel Pettyjohn to the former governor's scandal.

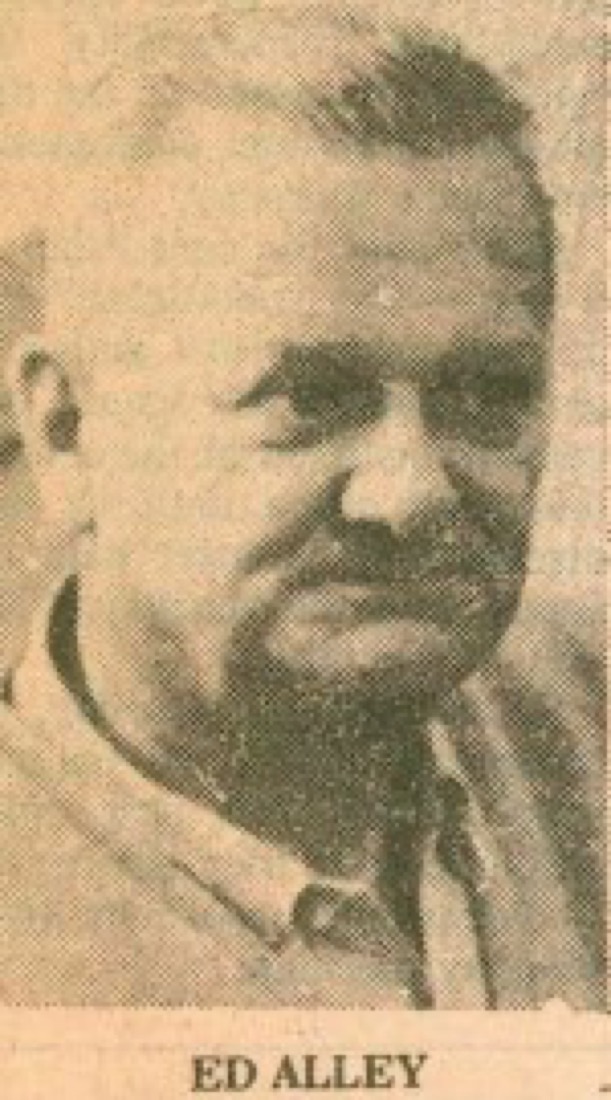

Pinkston said at a news conference that William Edward Alley - a known local criminal who died in federal prison on unrelated bank robbery charges in 2005 - was hired to kill Pettyjohn by Blanton's office and an undisclosed third party.

"Essentially, Mr. Pettyjohn cooperated with authorities and knew too much about what was going on locally, as well as the state level, and individuals didn't like that, and so individuals hired someone to murder him," Pinkston said. "Here we are some 42 years later."

Pinkston called Alley "a notorious bank robber" whose earliest known crimes dated back to 1933. Pinkston said during the news conference that witnesses and key players who initially lied to police and federal investigators had flipped and changed their stories over the past few years, which led the district attorney's office to confidently call Alley the gunman.

In the early morning hours of Feb. 1, 1979, Chattanooga business owner Samuel Pettyjohn - a local businessman, criminal and ally of Union leader Jimmy Hoffa - was shot four times outside of his own store at 20th and Market streets with a .45-caliber handgun and died immediately.

The case was odd from the beginning, according to Pinkston, who noted that a building Pettyjohn owned in Chattanooga had blown up several years before his death and that Pettyjohn had been found with more than $100,000 of jewelry on his person, undisturbed, at the time of the shooting.

The killer had also donned skin-darkening makeup and a disguise in order to not be recognized by Pettyjohn, who was known to carry a weapon and was found just feet away from a pistol.

The incident brought state and federal investigators to Chattanooga. Around that time, Blanton was involved in what's known as the pardon and parole scheme in which cash was given to the governor's office in return for certain people in jail to be released early.

Pettyjohn had been involved in that scheme and ended up cooperating with federal investigators on a number of occasions, Pinkston said. Pettyjohn also testified in front of a federal grand jury about what he knew about Blanton's scandal.

Pinkston and his office began a five-year, multi-stage investigation into the cold case in 2015. They were able to connect Blanton to the killing after it was discovered that payments for the killing of Pettyjohn could be traced back to Blanton's administration.

And Pinkston indicated Wednesday that Pettyjohn may not have been the only witness against Blanton to face a similar fate.

"There were five witnesses that cooperated with law enforcement against the Blanton administration that were either murdered or committed suicide," Pinkston said. "So we've talked to a federal judge who talked about another homicide, I believe in Columbia, Tennessee."

Pinkston and investigators said Wednesday that Pettyjohn's testimony could not be disclosed and that they were prohibited by federal court orders from giving that information out.

"Mr. Pettyjohn knew details from the very beginning [and knew] how the whole scheme operated," Pinkston said. "So he was very knowledgeable about what was going on."

Local law enforcement will consider the case closed, according to Pinkston, because a grand jury heard the case against Alley on Monday and confirmed there would be sufficient evidence for his arrest if he were still alive. When asked, Pinkston said he did not believe there were any other guilty parties alive in his jurisdiction.

Since there is no statute of limitations for first-degree murder, Pinkston said the office will remain open to further information about those involved.

Pinkston could not provide an exact number paid for the killing, but said the office had confirmed that a "portion" of the money came from Blanton's administration. The payment went through a third party and "obviously not directly from the governor's office."

Saadiq Pettyjohn, one of Samuel Pettyjohn's sons, spoke at the news conference about how grateful he and his family are to have closure in the case. He also told the story of how his mother and father met and about their first date in Alton Park, wanting to add some humanity to the story of his father's life and death.

"My father was a taxi driver, that's how he ended up meeting my mom," Pettyjohn said. "She was an elementary school teacher. She was walking her two sons to school. They had to either take a bus, take a taxi or walk. My father zoomed up and tried to put his best moves on her."

Pettyjohn also talked about the darker side of his father's story, of how he would always tell his wife that he would end up either in jail or dead.

"It's a curse and a blessing to grow up in a family that's connected to crime," Saadiq said, urging young community members in proximity to crime to choose a better path.

"When that person dies, you can either go that route, or you can go a different route. All of us chose to go a better route with education and try to do better in our lives."

Pettyjohn also said his mother, Julia Sims - who is alive and 90 years old - wanted to send a message that her late husband "had a heart of gold and was a very generous, giving person."

Saadiq Pettyjohn also said some members of his family are pushing for additional information on where the money paid to his father's killer came from and who may be held accountable.

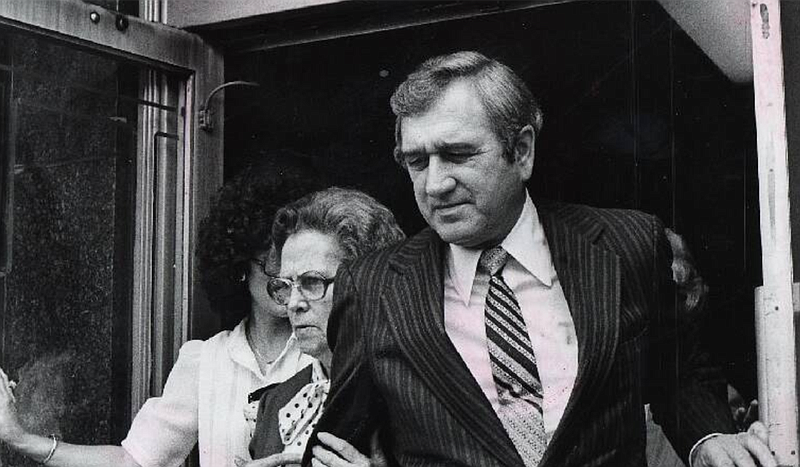

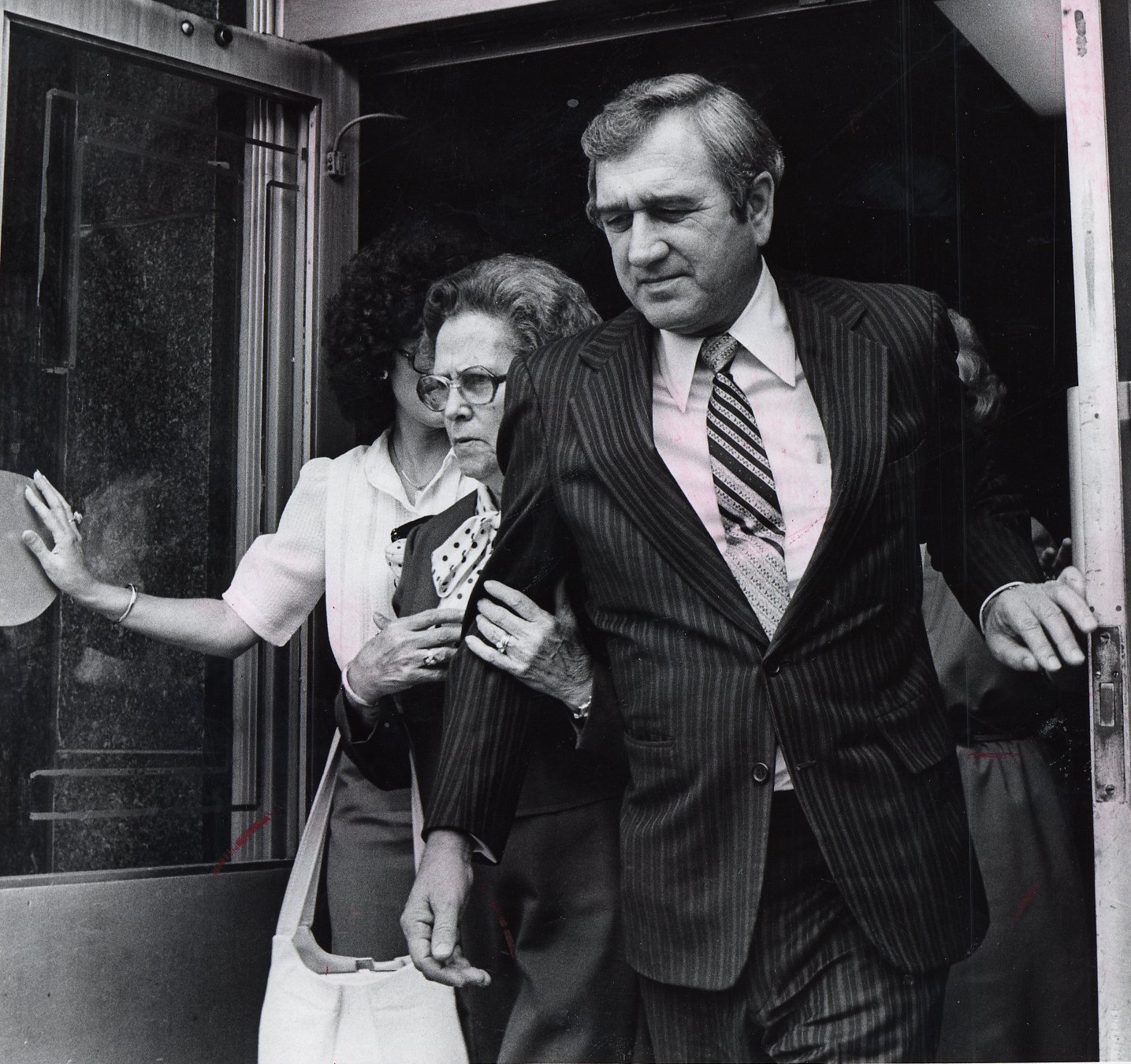

Blanton died in 1996.

Contact Patrick Filbin at pfilbin@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6476. Follow him on Twitter @PatrickFilbin.

Contact Sarah Grace Taylor at staylor@timesfreepress.comor 423-757-6416. Follow her on Twitter @_sarahgtaylor.