Earl Braggs' new memoir, "A Boy Named Boy," is a small book.

A digest-sized paperback, it slips perfectly into the back pocket of a pair of jeans. That is to say, it travels well.

This is ideal because even though Braggs cautions, "life doesn't happen in a straight line," life often does unfold on the open road, where a book like Braggs' memoir serves as a satisfying travel companion and life atlas.

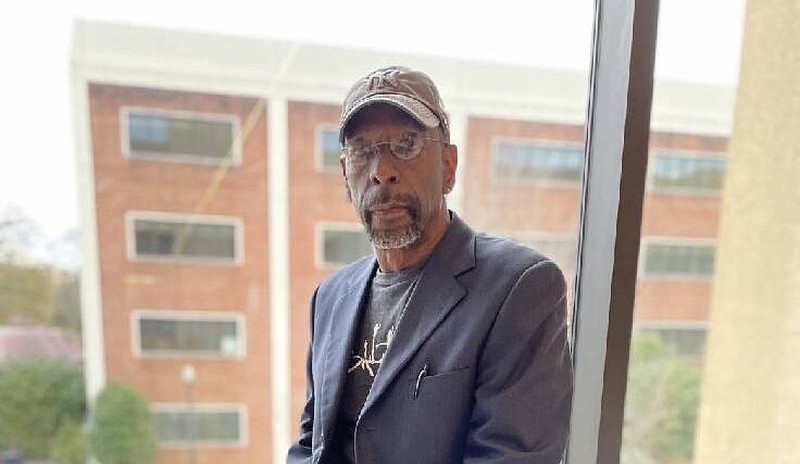

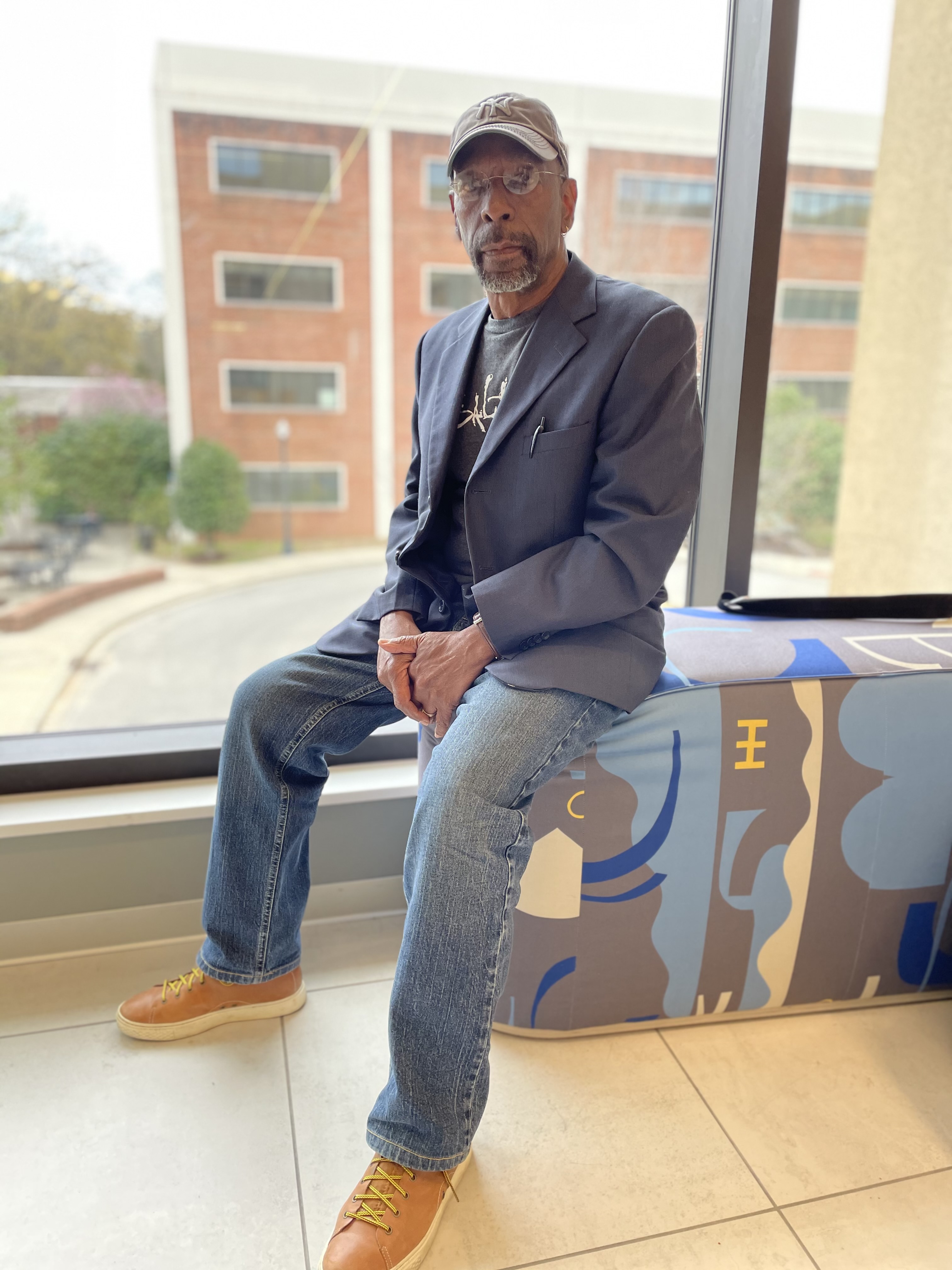

Braggs, a prize-winning author and the first African-American to hold a tenured professorship in the English department at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, has released his memoir (Wet Cement Press; Berkeley, California) at a moment of national reckoning on race. His students at UTC describe him as "brilliant" and "creative."

A child of the 1950s, Braggs' stories of growing up in a small, coastal North Carolina fishing town in the middle of the 20th century recall an era when crushing poverty and casual racism were baked into daily life for many Black people in the South.

Much of the narrative of the book is distilled from decades of Braggs' poems, which have examined the life lessons of his childhood and adult journeys. Braggs has published 14 collections of poetry, but this is his first prose book.

Growing up in Hampstead, North Carolina, in the 1950s, Braggs remembers sitting under his favorite oak tree 20 yards from the rent-free shack where he lived with his grandmother and siblings. There, along U.S. Route 17, he watched the world go by: the gypsies who he says once tried to lure him into the back of their car, the "goat man" who passed periodically but could not make eye contact, the gregarious local character named "Joe Bill" who could never finish a story.

All this led to a rich childhood, Braggs said, that belied his family's hardscrabble existence.

"I would describe [my childhood] this way," Braggs said, pausing to access his poet's voice, "It was a sad song, and I danced."

Braggs, who also lived for a time in the "red brick" projects of Wilmington, a bigger city located 17 miles south of Hampstead, says in the book that there's a difference between urban poverty and rural poverty.

"Urban poverty kind of eats you from the inside," he said. "Rural poverty feeds you from the inside. You are just as poor [either way] but one is eating you and one is feeding you."

Braggs said the white residents of nearly all-white Hampstead often gave his family venison, rabbit meat and "all kinds of pies for the holidays."

He also found happiness in books. He regularly rode shotgun with a Pender County bookmobile driver, and came to adore his school teachers, several of whom recognized his fondness for literature and his inquisitive mind.

The happy childhood took a turn when, as a high school student, Braggs was expelled for "inciting a riot" - a gymnasium brawl - that he did not start.

Braggs left town and later served in the U.S. Air Force - he was stationed in the Philippines during the Vietnam era. In due course, his memoir shifts to his adult travels in the United States, where he collected stories from the ordinary people he met on his journeys.

"I put a lot of value in listening, listening to people's stories, to how they unfold," Braggs said.

Braggs, who is the Herman H. Battle and U.C. Foundation Professor of English at UTC, is a winner of the Jack Kerouac International Literary Prize.

His next book, a poetry collection called "Children of Obama," will be released in spring 2022.

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com.