After more than a year of mask-wearing in her school, Sam Whittier's 9-year-old daughter was excited to see her teacher's smile this week without a face covering.

But two days after Gov. Bill Lee signed a law to essentially ban mask mandates in Tennessee public schools as of Nov. 12, a federal judge blocked the ban based on a legal complaint that the statute violates federal disability law.

A day later, the Whittiers' school board in Williamson County voted to lift its mask mandate anyway, based on declining COVID-19 cases.

"My daughter went from feeling very excited, to very let down, to very happy, all in a matter of days," said Whittier of the emotional roller-coaster from flip-flopping directives that he calls "mask whiplash."

(READ MORE: Mask mandate lifted at Hamilton County Schools)

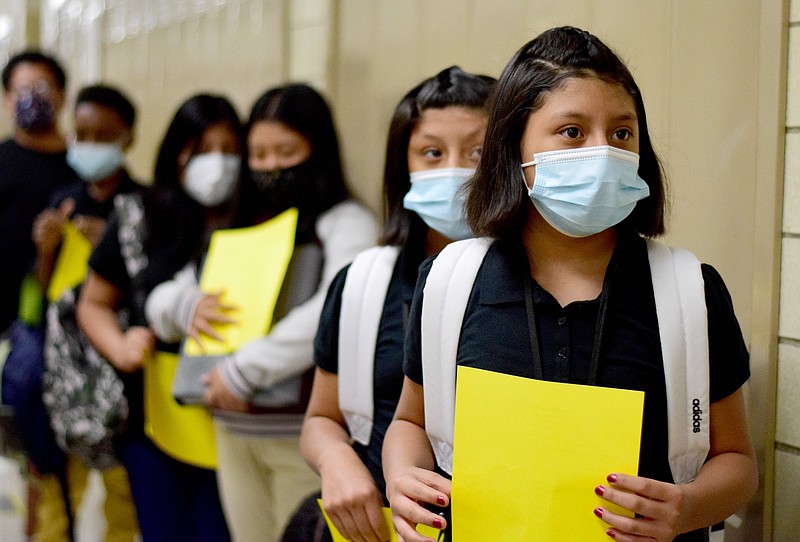

Battles over school mask mandates are playing out weekly in school board meetings and courtrooms, but it's the students and their families who must adjust on the fly to the changing orders.

"It feels like this isn't about common sense or mitigating the virus anymore," said Whittier, a father of three children in public schools south of Nashville. "It's become a political power struggle among adults, and unfortunately, our kids are caught in the middle."

The rules could change still again for his children's schools.

In Nashville, U.S. District Court Judge Waverly D. Crenshaw Jr. heard arguments Friday in the lawsuit filed by the parents of eight Tennessee children with disabilities who want the state law's masking provisions struck down. They say universal masking in schools is a reasonable accommodation for their children, who are more susceptible to catching the virus, and that the new law doesn't adequately protect them.

(READ MORE: Law limiting Tennessee school mask mandates still on hold)

The lawsuit also claims the state's rollback of mask mandates has put public schools in an "impossible" financial situation, since districts risk losing state funds if they don't comply with the state law, but could lose federal aid if they don't follow federal disability law.

A ruling is expected after Thanksgiving.

As lawsuits about masks have swirled around the state, Hamilton County has stayed out of the fray. The district imposed a mask mandate this year, with a parent opt-out - even before Gov. Bill Lee issued an executive order requiring such an opt-out be available whenever schools impose a mask mandate. His order faced several federal court challenges elsewhere, as it effectively pre-empted local mask mandates.

Hamilton County lifted any mask mandates Nov. 8, when the new state law was awaiting Lee's signature.

Statewide, families are generally sticking with what they're told by school administrators. But there's confusion there, too, as district staff try to untangle legal questions created by the new state law, orders from local health officials and rulings from federal judges in four separate Tennessee cases.

This week near Memphis, five suburban school districts switched from universal masking to optional face coverings, defying orders from the local health department and another federal judge's ruling that health officials still have authority to issue mask mandates.

"It's chaos," said Charles Lampkin, a Memphis dad and pastor who worries about long-term social and emotional impact to his six children attending a mix of public and private schools in Shelby County.

"The kids are watching all the arguing and bickering. They're the ones who are being hurt the most," he said.

Lampkin recounted two recent conversations with his sons.

His 12-year-old asked how young people are supposed to know the right thing to do when adults can't agree on something as simple as whether to wear a mask to keep the virus from spreading.

His 10-year-old, meanwhile, vowed that, when he grows up, he "won't put kids in these kinds of situations where they don't know what's going to happen next."

"It blew me away," Lampkin said of the talks. "This whole pandemic has been traumatic for our kids, and we adults need to be asking ourselves whether we are easing the blow for them or making it more profound. With all the fussing and quarreling, I'm afraid it's the latter."

Wearing a mask in school remains one of the most polarizing issues of the pandemic, contributing to the social and emotional toll on children who may also be behind academically due to disruptions to their education.

Therapists are seeing more cases of depression and anxiety among school-age children, many of whom are trying to process mixed messages about masking, said Stacie Hopkins, director of a child and adolescent treatment unit on the outskirts of Memphis through Lakeside Behavioral Health System.

"Children are faced with taking sides over how their parents may view the COVID policies," she said. "Some children have suffered panic attacks because they fear being exposed [to the virus] by a classmate who is not wearing a mask."

Hopkins urges adults to keep the lines of communication open with their children. Mask policies may be rapidly changing, but adults can provide consistent support and model good behavior.

"Continue to encourage children with basic health practices like washing your hands, covering your mouth when you sneeze or cough. It's OK to keep them updated on mask policies," she said.

But some parents have taken more drastic measures over mask confusion and COVID policies.

Nicole Wilkins of Memphis is now homeschooling her three teenagers, while Franklin parent Monique Koupal has moved her 8-year-old son from Williamson County Schools to a private school in Nashville. Private schools aren't covered by the new state law and are free to set their own mitigation policies.

"We left public schools to avoid all the inconsistencies," Koupal said. "My son is anxious and has ADHD, and I knew he wouldn't be able to handle mixed messages on things like masks."

Sam Whittier and his wife are sticking with public schools in Williamson County and trying to provide extra support during all the transitions. They also avoid talking negatively in front of their children about the conflicting orders and confusion. But it's a challenge.

"I'm frustrated with all the back and forth and all the political fighting," Whittier said. "People seem to want to lump you into being on one side or another of this debate, but there's so many people in the middle who just want to see common sense. We need to move in that direction - because COVID is not going away."

This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.