When Education Secretary Miguel Cardona appeared before Congress in September to promote the Biden administration's stimulus funding for schools, he promised tutoring to help students make up missed learning as well as an end to instruction through screens.

"Not only as an educator, but as a father, I can tell you that learning in front of a computer is no substitute for in-person learning," he said.

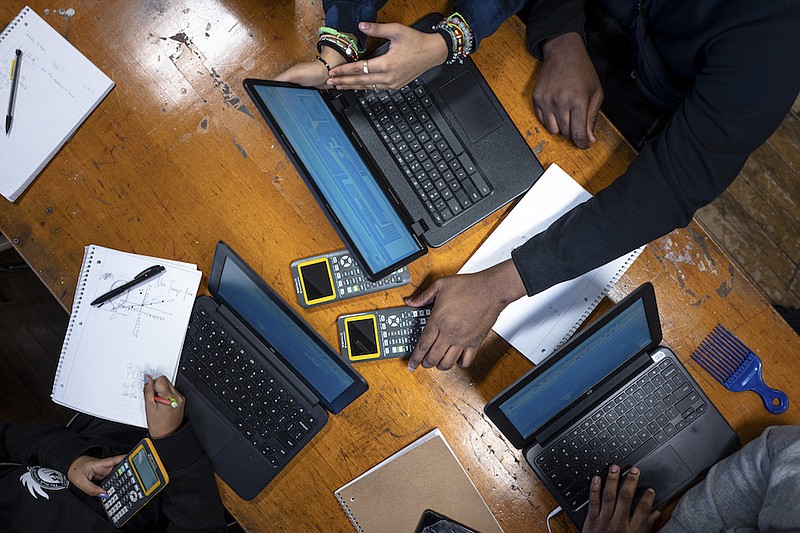

The stimulus bill, known as the American Rescue Plan, will send $122 billion to schools over three years, and a sizable portion of that money will go toward tutoring. But because of labor shortages, the high cost of quality tutoring and the influence of a growing ed-tech industry, much of the tutoring will itself take place through a computer screen - and not always with a human on the other end.

For-profit companies and nonprofit groups are selling virtual tutoring services to school districts. Some programs use live video to try to replicate in-person tutoring as closely as possible. Others skip the human tutor and use artificial intelligence. And some are essentially instant-messaging services, with students and tutors randomly paired for brief typed chats, often organized around homework assignments.

Spending on virtual tutoring is explicitly allowed under federal stimulus guidelines, and the Education Department said quality remote tutoring can be a "great option for many students, as long as the tutoring addresses individual students' needs and produces strong educational outcomes."

But the idea of online tutoring as a fix "confounds me," said Laura Vaughan, a parent in Montgomery County, Maryland, a suburb of Washington that had some of the longest school closures in the nation. Her 13-year-old had a frustrating experience with both remote schooling and virtual tutoring. "Just watching my son trying to pay attention to virtual anything is hard," she said.

The online tutoring field is fairly new, and many companies said they either did not have data proving their program's effectiveness or were still collecting it. Several pointed to small studies from Britain and Italy showing promising results.

But critics say online tutoring rarely matches up to in-person tutoring and that only a few such services replicate strategies that research has shown to be most effective: a paid, trained tutor who has a consistent personal relationship with a student sessions during the school day, so that students do not skip lessons, and at least three sessions per week.

"A key piece of tutoring is that social relationship with a caring adult," said Amanda Neitzel, an assistant research scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Research and Reform in Education. "How can you build that in an online format?"

Her worry, she added, was that the federal tutoring push would amount to "an expensive disaster."

Virtual tutoring is a big business opportunity for the education technology sector. Investment in ed tech surged to $3.2 billion in just the first half of 2021 from $1.7 billion in all of 2019, according to market research from Reach Capital, a venture capital firm specializing in education.

Now some online tutoring startups are drawing half their new business from federal funds, according to James Kim, a partner at Reach. Districts typically pay $1 to $100 per student who will use tutoring services over the course of a year.

Ed-tech investors and entrepreneurs say the academic and social failures of remote school have little to do with the services these businesses are offering. They emphasize that their platforms are supposed to supplement in-person education, not supplant it, and that being able to get a tutor anytime, from anywhere, has benefits.

"Online tutoring is a one-on-one communication," said Myles Hunter, CEO of TutorMe, which pairs students with tutors - mostly recent college graduates - over audio, video or instant messaging. "It's not something where you're trying to make sure 40 students don't fall asleep watching a Zoom video for eight hours per day."

Nevertheless, Kim, a former teacher, understood the doubts.

"I think the cynicism is justified," he said. "I was pitched a lot of technology products that just didn't have a place in my classroom. Especially during this pandemic, when there was a lot of money in this market, we saw folks looking to make a quick buck."

Some cities and states - like Chicago, New Mexico and Arkansas - are starting in-person tutor corps. But hiring has been difficult because of labor shortages, a major reason district leaders said they were turning to online tutoring.

Many administrators say they cannot fill in-person tutoring jobs that pay $15 to $22 per hour, sometimes without benefits. Starbucks can be a more attractive employer, said Tom Philion, dean of education at Roosevelt University, which has partnered with Chicago Public Schools to hire and train tutors.

Online tutoring jobs attract many more and better-educated applicants, hiring managers said.

But tutoring businesses vary in quality and have experienced significant growing pains.

Last school year, Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland signed an $834,000 contract with TutorMe. Vaughan's son, Caleb, 13, tried the service several times in May for math help. But Caleb was never paired with tutors when he tried to use the platform on several Sunday afternoons. He signed off, frustrated.

Hunter of TutorMe said that there had been challenges, associated with a 600% increase in requests during the pandemic, but that it was "uncommon" for a student not to be paired with a tutor. The average student is paired with a live tutor in 43 seconds, according to the company.

TutorMe has served 1,200 K-12 schools. Montgomery County Public Schools received $252 million from the American Rescue Plan and said it would spend $14 million on tutoring. Its contract with TutorMe has expired, but the district identifiedtwo other virtual tutoring companies that will receive a total of $3 million. Some students are receiving tutoring from school staff, which is primarily remote.

Even when online tutoring services work, the amount of screen time can be a concern, especially for younger students who need to develop hands-on skills.

Brewbaker Primary School in Montgomery, Alabama, uses an artificial intelligence program called Amira, which is distributed by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and used by at least 1,000 schools nationally.

Amira is known for helping children with phonics and phonemic awareness - the unique sounds associated with English letters and letter combinations - which are crucial to learning how to read.

The software features an interactive avatar that teaches children how to sound out words, listens to them read aloud and makes corrections. Brewbaker students in kindergarten through second grade are expected to use the software each day: 30 minutes at school and 30 minutes at home. Brewbaker also uses Amira in its optional after-school tutoring program, paid for by federal funds.

But after missing months of hands-on classroom work, many children at Brewbaker are struggling with fine motor skills, the principal, Jaclyn Brown Wright, noted. Some second graders cannot tie their own shoes or open a carton of milk and are still struggling to form written letters. Others are slow in building their social skills.

"Even though we access technology, we still put pencil to paper and crayon to paper," she said.