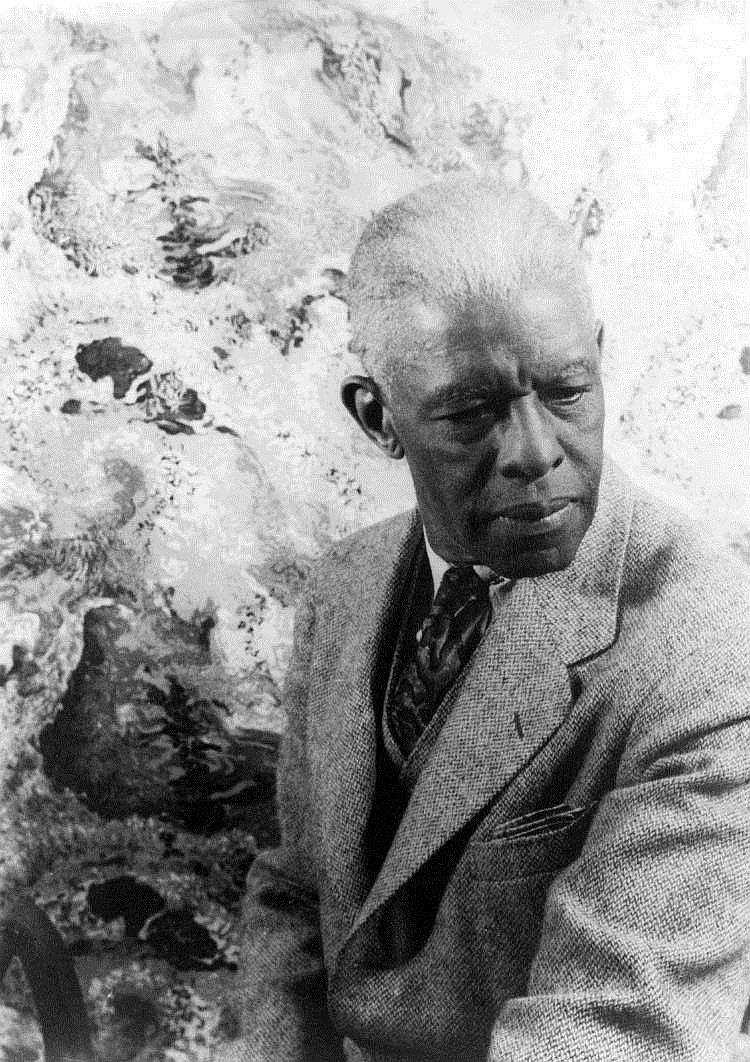

For roughly the first half of the previous century, Roland Hayes (1887-1977) was almost universally acclaimed on the international classical concert circuit for his uniquely moving tenor sound, his impeccable diction in several languages and his riveting dramatic expression. By 1920, he quite literally was "appearing before the crowned heads of Europe."

His stratospheric vocal career was not only improbable because he rose from relative poverty in segregated Chattanooga to worldwide fame before sophisticated audiences. That journey presented obstacles enough, many of them recalled in the current special exhibition at the Bessie Smith Cultural Center: "A Tribute to Roland Hayes" (closing Oct. 31).

But the heights of his achievements cannot truly be appreciated without some understanding of the peculiar challenges of classical singing.

In the first place, a classically trained voice must fill a concert hall without resort to any kind of amplification (OK, novelty acts like The Three Tenors in Giants Stadium get a pass). Except for the rarest natural aberrations, the concert singer must train for years to develop the required and daunting physical techniques to gain the stamina to rise above (perhaps) a full orchestra over a long evening.

Then there are the foreign concert pieces to memorize and pronounce correctly - not only French, Norwegian, Russian and Italian, say, but the subtly different German of Bach from that of the later Schubert. More years, more tons of money to teachers.

Somewhere therein lies the genius - or perhaps, "divine madness" - of Hayes's almost inexplicable ambition.

In an oft-told anecdote, the 17-year-old discovered in a church choir, was introduced to a Chattanooga Times editor, who played for him a scratchy recording of Caruso in full cry.

In that instant, Roland heard his future. (Never mind that he would become a lyric tenor, not a bellowing Italian bull).

As origin myths go, that's pretty good, but it does not at all explain why this particular young man, lacking even a complete high school education, suddenly determined that he would head out of town and support himself and those singing lessons.

Marian Anderson once said, "If it weren't for Roland Hayes, I never would have dared try."

I think she meant the whole package - not just race, perceived obscurity, bewildered family and friends - but (in both of these cases) a "divine madness" that changed the world. Incredibly, they did not fail.

In our 21st century, Hayes almost has been forgotten outside classical circles, less elsewhere than here at home. The Boston Public Library, among other institutions, holds a very strong collection of memorabilia. The Boston Symphony Orchestra occasionally celebrates his memory in concerts.

Why should we honor him here?

Listen to that softly penetrating voice

"Du Bist Die Ruh" - The Schubert lied (German song) Hayes sang to a hostile, defeated German audience after World War I and memorably won them over in the moment. Although most of his recordings were made fairly late, the sweetness of tone and heartbreaking empathy of this lied still spring from the vinyl.

"He Never Said a Mumberlin' Word" - Hayes said that his African-born grandfather, a slave, composed this bone-chilling, unforgettable song about Christ's crucifixion.

And so forth, throughout his diverse catalog.

By the way, I once met an African-American tenor, a professional madrigal singer, who said, "Poor Roland Hayes. He was forced by racist promoters to sing spirituals in concert halls."

No. Just the opposite.

Hayes was the first classical recitalist to insist that the music of his heritage be included on the same stages as the beloved lieder and chansons (chanters) of Europe.

That legacy shines brightly today in the performances of almost any person of color at Carnegie Hall and other signature houses.

Go to The Bessie for his story. Then, whether there or elsewhere, listen to the man sing. These decades later, he will draw you in. He will be forgotten no more.

Charles Flowers, a 1960 graduate of Chattanooga High School and a donor to the Hayes exhibit, has written or co-authored more than 70 nonfiction books, including the "Instability Rules." He lives in Purdys, N.Y. For more, visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org.