The state of racial relations in Chattanooga appears to be in line with our nation's present polls - the large majority of black and white Americans rarely interact with each other in any meaningful way.

Therefore, the future of race relations in Chattanooga can be predicated on two questions:

- Will black and white citizens reach out to communicate with each other?

- Will black and white citizens do this with genuine intent to build true friendships?

A positive answer to these two questions will require intentional acts. Black and white citizens must decide to greet each other, speak to each other, sit and talk with each other, share ideas, concerns, hopes and dreams, just as any other people who want to know each other.

But first, we must care. That requires believing the other is worth caring about. Not everyone believes that. We only have to watch people's actions to know this. What many white citizens do not seem to recognize is that positive actions on our part - intentionally given - could erase the racism that has existed for years. Do I believe that? Yes, I do. Can it happen? Only if enough Chattanoogans care - from richest to poorest, from the mountains to the valleys, from management to labor, from churched people to unchurched people - from every corner of the community.

When my wife Tresa and I returned to our hometown in 2012 after being away for 41 years, we thought we would find a city substantially changed in terms of racial relations than when we left in 1971. Admittedly, some positive change has taken place. But as we visited various, previously all-black venues for concerts and other events, they were still almost all-black, and all-white events were still almost all-white. "Eyeball research" reveals little trend toward true integration. We invite other Chattanoogans to try this out.

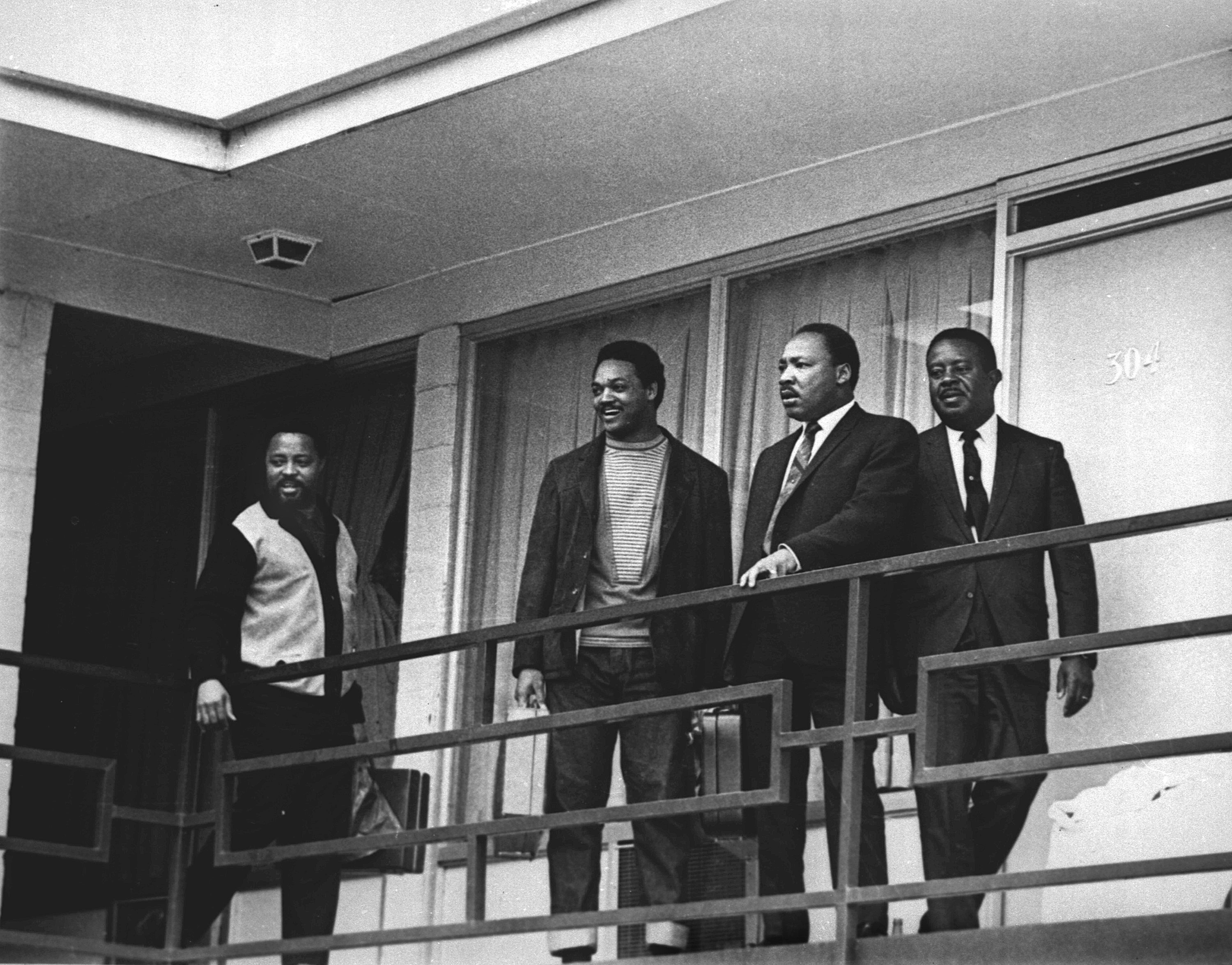

FILE - In this April 3, 1968 file photo, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. stands with other civil rights leaders on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., a day before he was assassinated at approximately the same place. From left are Hosea Williams, Jesse Jackson, King, and Ralph Abernathy. King is one of America's most famous victims of gun violence. Just as guns were a complicated issue for King in his lifetime, they loom large over the 30th anniversary of the holiday honoring his birthday. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this April 3, 1968 file photo, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. stands with other civil rights leaders on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., a day before he was assassinated at approximately the same place. From left are Hosea Williams, Jesse Jackson, King, and Ralph Abernathy. King is one of America's most famous victims of gun violence. Just as guns were a complicated issue for King in his lifetime, they loom large over the 30th anniversary of the holiday honoring his birthday. (AP Photo, File) Thus, a negative answer to the question of building positive racial relations requires only a continuation of a lack of interest, lack of concern and lack of empathy for each other which has been fed by years of culture and habit. Most black people I meet do not believe that the majority of whites care enough to break down these unwarranted, sometimes ignorance-based, sometimes racism-based barriers to our friendship and communication. It's the reason a black friend walked into our home for an interracial discussion one night when there were 60 guests - 30 white, 30 black - and asked, "Are there really this many white people in Chattanooga who care about this subject?" The white man who followed him into our home looked at the 30 black guests and asked incredulously, "Do you know this many black people?"

My answer to both questions was "Yes," and that answer stunned both participants. The black man felt sure there were not that many white Chattanoogans who cared enough about black people to meet in a home to talk about what it means to be black in our society. And the white man had no idea that any white resident might know 30 black Chattanoogans as more than anything but passing acquaintances, certainly never friends. Sadly, neither the black guest nor the white guest had ever had my wife's and my experience, and they were both over 50 years of age.

We have now had 12 of these meetings with over 400 different people attending, and in almost every meeting at least one new black friend whispers to me, "I have never before been in a white home for a social event."

I hasten to state that there are other white and black citizens in Chattanooga who, I am delighted to say, have shared the same positive experience my wife and I have. But we are not speaking of thousands, probably not even hundreds. Maybe just dozens, and that would be a shame.

After the two questions from the black and white men entering our home, I asked my first question to the group: "White folks, how many of you have a good black friend?" Only two hands were raised. I asked the opposite question of the black guests. Eleven hands went up; however, one black guest said, "But we don't invite white friends to our home." And a black female added, "We just don't trust white people. You act one way when you're with us without other white friends, and you act another way when there are white friends around."

Tresa and I have white friends who care about black people, yet some of them still ask us, "What do I say to a black person?" I tell them I say the same kinds of things I say to white people I don't yet know: "Hello, I'm Franklin McCallie. Who are you?" I do that when I think it's appropriate; when standing in a long grocery line, or when I'm sitting near someone on the downtown electric shuttle, or when we have spent what could be a long or awkward time in an elevator. That kind of conversation breaks the ice. Many times, I begin with the same subjects as I do with people who are of the same race or color: the weather, the interminable wait in line, something I like in their grocery basket. The point in any of this conversation is to show that we are all Chattanoogans, and we're not going to let an unwarranted distance stand between us.

If you are someone who has trouble doing that with a stranger, is it possible to initiate enough courage to say to a person of another color - an acquaintance or a business associate - "Would you like to go to lunch today?" Or, "How about meeting me for coffee tomorrow morning?"

There are contemporary studies that show that white business associates of all ages mostly go to lunch with their white colleagues, while black business associates mostly go to lunch with their black colleagues. In these lunch sessions, there is not only talk of a purely social nature - family, etc. - there is also much sharing of professional talk about what is happening in the company and what jobs might be coming open. Unfortunately, this information is not shared across the almost impenetrable color barrier. White businesspeople have the most access to important information and keep their information in their own "circle of gossip." And yet, this information is needed by all work associates - of whatever color - in order to move up the ladder, be given more responsibility and earn better salaries. Equally as important, at every level, when people of greater diversity are included, discussions can be broader and deeper because all viewpoints are included. Studies have shown, and many business leaders attest to the fact, that diversity brings more creative ideas, more possible solutions. Corporations and businesses prosper that make profound commitment to inclusion of all ethnicities, all colors.

Young Chattanoogans who are reading this column might be smiling in disbelief. "Really? Old people have these kinds of problems with each other in 2016?" I would counsel young people to set aside any complacency they might have about how quickly we are moving into multi-racial acceptance and involvement. We activists of the '60s were convinced we saw racial nirvana ahead, and 40 years later, we're still searching. I have witnessed local high school and college cafeterias, and pizza parlors where the young professionals gather after work. I am not heartened by what I see. Too many times there are groups of one color sitting together. I would not worry about that if I saw a reasonable number of groups crossing the color line, but I see few of these. That's not what I call "building interracial friendships." Rather I call that "staying with those with whom you feel comfortable."

So the question remains, why are we not comfortable with each other across the color line? My best answer is that we've had little to no practice. Practice demands intention. Without intention in building genuine, interracial friendships, contemporary young people might find themselves writing a similar essay for Chatter 40 years from now.

So, is there an answer for Chattanooga? Are we destined to live out our social and professional lives side-by-side but having little or no contact across racial and color lines? Is that what we really want? Is there nothing to be learned or appreciated from someone new? Is it too difficult for us to reach out? Are we too afraid of each other? But also ask the question: Can Chattanooga afford to deprive our city of better ideas because we are uncomfortable with each other? If corporations and businesses prosper through inclusion, might not our entire Chattanooga community prosper too?

I hear all over this town that we are committed to being "Chattanooga Strong." Is it possible we can also commit ourselves to being "Chattanooga Connected?"