"The past is never dead. It's not even past."

- William Faulkner, "Requiem for a Nun"

I grew up with a portrait of Robert E. Lee hanging in the living room of my parents' home. It was displayed in a frame made of wooden planks from my father's childhood home, a Depression-era shack in rural Maury County.

My sister's first name is Lee, and my bank lock box contains a small, fragile book of family history that traces blood connections between my father's Middle Tennessee clan and the Confederate general. As near as I can tell, we are distant cousins.

Growing up, I found the Lee family tree compelling. I even read a book or two about Lee's complex relationship with the Confederacy. He was a decorated U.S. Army officer who was initially opposed to secession.

No student of Civil War history, I have remained ambivalent about this Lee connection, filing it in my brain under "family trivia." Whole decades have probably passed without me mentioning it to anyone.

The family connection to Lee raises no particular feelings of pride or shame. For good or ill, one's family is an accident of history. It's what we do in the present that matters. Lee's portrait was passed down but eventually made its way into attic storage somewhere. Meanwhile, I abhor the idea of slavery and deeply regret the Antebellum-era South's role in perpetuating human bondage.

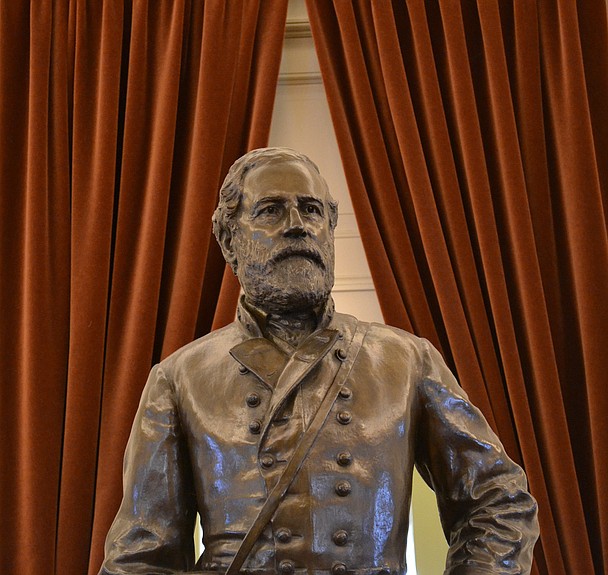

I was thinking about this last Saturday while reading news feeds about the events of Aug. 11-12 in Charlottesville, Va., where clashing protesters again spilled blood on American soil. It was the planned movement of a statue of Robert E. Lee that was the pretense for the gathering of white supremacists, which resulted in resistance from counterprotestors.

With my smartphone in hand, I sat on the bed and watched a Facebook video of a car plowing through a crowded street, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer and injuring many more. At the moment of impact, the camera picture went askew and people started screaming.

Later, I was struck by one thought: Many of the protesters and militia members in Charlottesville were armed to the teeth; we may never know how close we were to a national conflagration there. Faint echoes of the Civil War - Americans bearing arms against Americans - were hard to ignore. In our fast-paced, modern world, we forget that the embers of great wars sometimes take many generations to cool.

View other columns by Mark Kennedy

At some point last Saturday, my gaze shifted to a folded American flag encased in a triangular shadowbox in the hall of our house. It was the flag that draped my father's coffin when he died in 1993. He was a master sergeant in the Korean War, where he slept on the ground every night for a year and rose through the ranks as his buddies were killed around him.

Decades after the war ended in 1953, he would wake trembling at night, dreaming he was being bayoneted in his sleep by North Koreans. He also struggled with health problems and addictions. This was before post-traumatic stress disorder was fully understood.

In recent years, it has been comforting for me to realize that my father's suffering had at least made life easier for people in South Korea over the last 60-plus years. The differences in the divided country are stark. In impoverished, famine-stricken North Korea, there are 24 million people living on an per capita income of $1,800 a year. Meanwhile, South Korea is a thriving nation of 48 million souls with a per capita income of more than $32,000 a year in U.S dollars.

If there is a better argument for freedom over dictatorship than the 38th parallel, I'd like to hear it.

Still, this month's saber-rattling from both North Korea and the U.S. shows how fragile peace can be. Even though the brinkmanship has cooled some in recent days, I fear that Americans who have grown up outside the shadow of America's great wars have forgotten the human carnage that results when two well-stocked conventional armies engage - God forbid an actual nuclear exchange.

We study history so we don't forget Gettysburg, where the armies of the North and South experienced more than 50,000 combined casualties; and Hiroshima, where up to 146,000 people died in the atomic blast and its immediate aftermath.

For nations, war wounds take decades - even centuries - to heal; witness the suffering still being wrought from wars fought in the 1860s and the 1950s.

Many Americans in 2017 seem to have cavalierly adopted public conflict as entertainment. This is like playing with dynamite. History teaches that political theater can quickly devolve into unimaginable human suffering.

Just ask any warrior - even one on a statue.

"It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it."

- Gen. Robert E. Lee

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-645-8937.