View other columns by Mark Kennedy

If I had an Oscar vote, my "Best Movie" pick for 2016 would go to "Hidden Figures," a film about a team of black, female mathematicians who provided support for the U.S. space program.

Expect nostalgia about the space program to peak as we approach the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong's historic first moon walk in a couple of years.

For those of us over a certain age - about 55 - our memories of the first moon walk are still vivid. You can argue that nothing in human history the last half century is as important as that first moon walk.

To my two sons, ages 10 and 15, the Apollo moon landings are as distant as World War I was to us baby boomers growing up in the 1960s.

The "Hidden Figures" film (and book of the same name) are remarkable on several counts. First, before Margot Lee Shetterly's book about the black mathematicians at NASA's Langley (Va.) Research Center, few people knew of their contribution to the space program. Second, the film's portrayal of the casual racism practiced by the white professionals at NASA in the early 1960s (separate bathrooms for blacks and whites in a NASA facility?) is jarring.

In one scene in the movie,

the film's main character, a "computer" named Katherine G. Johnson, is called in to scrutinize the math in John Glenn's flight plan.

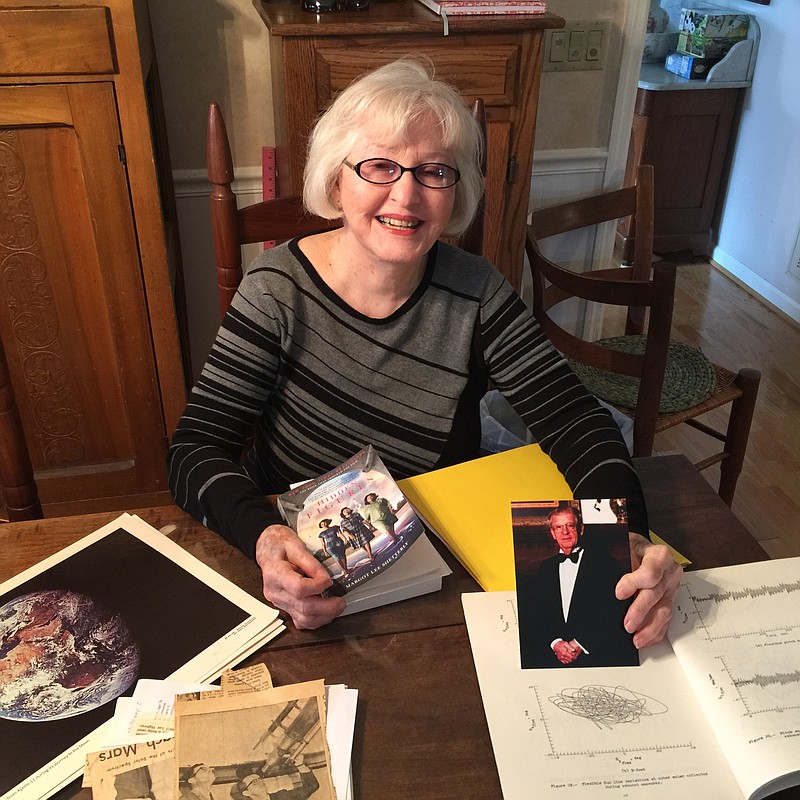

Recently, we learned that a Times Free Press reader, Elizabeth Worthington, had a brother, the late John Young, who was an engineer at Langley in the 1960s, as well. He is named several times in the "Hidden Figures" book, and was an associate of both Johnson and Glenn, who later visited his home in Virginia and became a personal friend.

Young, whose career was centered in NASA's flight dynamics control center, died in 2012.

Elizabeth and her brother John were playmates as kids. Hailing from Grassy Creek, N.C., they spent their formative years romping around the campus of Emory and Henry College, a small Methodist school in Emory, Va., where their father was a math and physics professor.

With many of her brother's personal papers, including two eulogies and an obituary, spread out on her dining room table in suburban Chattanooga, Worthington ruminated about having a sibling so close to the action.

"I miss him," Worthington said. " He never cracked a book, and I had to study hard to get good grades."

After graduating from the University of Virginia, Young, who followed his father down the math/physics path, took a job with NASA, where he authored such esoteric studies as "Trajectory Optimization for an Apollo-type Vehicle Under Entry Conditions Encountered During Lunar Return."

He became famous at NASA for conducting a seven-year study of the mechanics of a manned space mission to the outer planets. His study proposed something called the "Grand Tour." Basically, he discovered that once every couple of centuries, the planets line up in such a way that a spaceship could literally be pinballed from one planet to the next through sheer force of gravity.

His eulogists noted that despite his big brain and fabulous intellect, Young - a man who had helped enable the lunar landings - also had an absent-minded side that combined with a dry wit.

Once, for example, he is said to have started limping after developing a chronically sore foot, only to discover his problem was a wad of packing paper stuffed in the toe of a pair of dress shoes.

Another time, he and his chemical engineer brother Phil, who was also brilliant, made a crude, ground-busting machine out of a spiked, 40-gallon drum filled with concrete; not allowing for the fact that their invention would weigh about 1,000 pounds and be virtually unmovable.

Humbled, they were reduced to digging a big hole right in front of the contraption and quietly rolling it in.

Ouch.

These whimsical scenes will no doubt be in the movie when John Young's envisioned "Grand Tour" to all the planets actually happens in some distant century.

If the Oscars still exist, perhaps it will even win the "Best Picture" award.

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645.