Presidents Day Timeline

* 1799 — George Washington, the first United States president, dies, and his Feb. 22 birthday becomes a perennial day of remembrance.* 1879 — Congress votes to make Feb. 22, Washington’s birthday, a holiday in the District of Columbia.* 1885 — Congress votes to expand the holiday to the entire country.* 1951 — The National Association of Travel Organizations floats a plan to combine Washington’s and Lincoln’s birthdays and celebrate them on what would be called Presidents Day on the third Monday in February. A few states adopt the idea.* 1968 — Congress approves the Uniform Monday Holiday Bill, moving Washington’s birthday to the third Monday in February.* 1971 — Since Abraham Lincoln’s Feb. 12 birthday is recognized as a holiday by some states, when the Monday holiday bill takes effect, some states begin to refer to the holiday as Presidents Day.* 1999 — A pair of bills fails in Congress to move the unofficial Presidents Day back to Feb. 22 but keep the name because two other presidents — William Henry Harrison and Ronald Reagan — also were born in February. Thus, the official national holiday is actually still Washington’s birthday.

"In the scheme of our national government,

the presidency is pre-eminently the people's office."

- President Grover Cleveland

George Nelson got that feeling about the presidency when he was just a boy. On a family vacation in Gettysburg, Pa., he stood outside a white wooden fence and looked directly onto the grounds of the farm owned by the president of the United States, one Dwight D. Eisenhower.

When he wasn't at the White House, Nelson was told, the president would be there. He could practically reach out and touch the green grass in the president's yard.

"Seeing his farm, as a little kid, from a little nothing town, I was pretty taken with it," says Nelson, 66, a Chattanooga businessman. "It started way back then."

"It" is his fascination with, and interest in, presidents.

You might not know, but Nelson does, that Abraham Lincoln was an honorary pallbearer at John Quincy Adams' funeral. You might not know, but he does, that Tennessean James K. Polk was the first president to regularly have "Hail to the Chief" played at his arrival because his short stature often caused him to enter a crowded room unnoticed. You might not know, but Nelson does, that the White House was called the Executive Mansion before the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt.

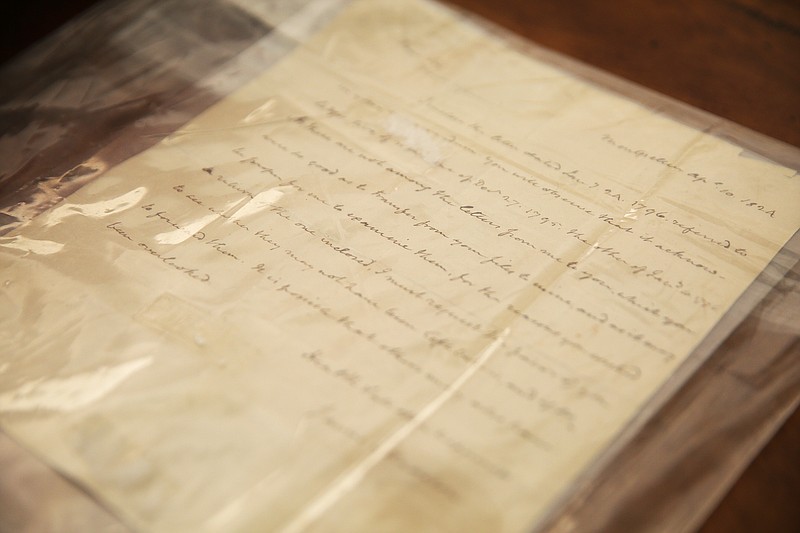

Today, the day before the country marks what is unofficially called Presidents Day (see timeline), the western New York native can do more than touch a blade of the president's grass. He can open a bound portfolio and show visitors an actual letter George Washington wrote just months before his death. He can point out one of four copies of Richard Nixon's resignation letter to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. And he can show you a missive that explains why Lincoln was writing to free a Confederate prisoner in 1864.

Nelson, for 30 years, has collected presidential signatures and various documents and memorabilia signed by most of our 45 chief executives.

He's got something with the John Henry of nearly all of them. Many of them are handsomely framed together with explanatory plaques and pictures, and many of them hang on the walls of his finely appointed home overlooking Chattanooga. Others are signed Easton Press leather-bound editions of presidential autobiographies and books, including a book by Nixon inscribed to Manuel Noriega, the former Panamanian dictator who was removed from power with U.S. help during the term of George H.W. Bush.

Nelson prefers not to divulge the worth of his collection but does allow that several pieces are valued "in the low six figures."

He started small, he says, with presidential "clip" signatures, authenticated signatures that years ago were clipped from letters, documents or other paperwork. Lesser presidents such as Martin Van Buren, Franklin Pierce and Rutherford B. Hayes are represented in his collection this way. Such signatures, he says, can be obtained today for a couple of hundred dollars.

Another is that of the 13th president, Millard Fillmore, who perhaps guessed someone might try to forge his name one day. His reads: "Autograph of the president of the U. States/Millard Fillmore."

Most recently, Nelson has collected letters from one president to another. Letters from John Adams to James Madison and Thomas Jefferson to Madison are his newest. But he also has letters of Andrew Jackson to Van Buren, Warren Harding to William Howard Taft and Harry Truman to John F. Kennedy.

"I'd like to have [John] Adams to Jefferson," he says, mentioning the long feud and reconciliation between the second and third presidents, the fact they died the same day, and the oddity that the date - July 4, 1826 - was the 50th anniversary of their signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Nelson became interested in collecting while living in Florida. A man in the development department of his business, he says, collected Kennedy artifacts. He even had a piece of paper with something the martyred president scribbled on the fateful Air Force One ride on Nov. 22, 1963, from Fort Worth, Texas, to Dallas, where he would be killed.

"I thought it was really interesting that somebody in the public could get an item like that," he says.

Collecting is much easier in the internet age, Nelson says. To demonstrate, he picks up his cellphone, taps out a request and in a few seconds finds Washington letters on sale for $28,000, $50,000 and $170,000.

Now, he says, he doesn't purchase just anything but looks for condition, content and historical significance. "I can be much more selective," he says.

Nelson once thought he would buy the items as an investment and sell them later. But he kicks himself for selling the ones he did, a letter from Aaron Burr (who served as the country's third vice president) and a letter from Confederate States President Jefferson Davis. He would like to have both back because he now has letters from Alexander Hamilton (Burr's duel opponent in 1804) and Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee (Davis's Civil War co-combatants).

Now, he says, he likes having them around, likes to admire them from time to time. They've become, he intimates, almost like a living history.

Nelson balks at naming a favorite presidential document of his and instead relates a story that would be a goosebump-inducing moment for any collector.

A letter he has from Washington finds the first president inquiring as to how he might pay for two etchings portraitist John Trumbull did for him.

Some time after he purchased the letter, when Nelson was at Washington's Mount Vernon home for a small-group tour for supporters of the home's Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, he mentioned to the guide the letter he had bought. The guide pointed to etchings on a wall on the Potomac River side of the home and told him those were the very etchings the letter referenced.

A letter that piques his sympathy is a personal note from Benjamin Harrison written during his one White House term in response to a question about his wife's health.

His wife, Caroline Scott Harrison, began to suffer from tuberculosis during the third year of her husband's term and died just months before the end of his term.

The president's letter suggests that his wife is a little better but has a long way to go.

The letter Nelson says he paid the most for is not from a president but from Lee, the Confederate commander, to his generals, telling them he doesn't hold them responsible for the South's loss of the war.

One that generates interest but didn't cost a lot was the Nixon resignation letter, which is written on the official watermarked White House stationary. There reportedly are only four copies of the letter. One is in the National Archives, one in the Smithsonian Institution and two are in private hands (one of which is his).

Elsewhere, among his other artifacts, are a 1783 letter from Jefferson asking for reimbursement of expenses, a photograph at the opening of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library signed by Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Reagan and George H.W. Bush, a photograph signed by Nixon, Ford, Carter and Reagan when Reagan dispatched the other three to Egypt for Anwar Sadat's funeral in 1981, a full-page letter by Founding Father Benjamin Franklin (Nelson's oldest, penned in 1747), a signed copy of Ford's pardon of Nixon, and the signature of David Rice Atchison, who is dubiously credited by some for being president for one day (in 1849 when incoming President Zachary Taylor refused to be inaugurated on a Sunday, the day his predecessor Polk's term ended.

Of the 45 chief executives, Nelson says he most admires Reagan, who not only was president when Nelson bought his first business but also brought "renewed patriotism and sense of growth" to the country.

"I just appreciate the way he did things," he says.

Not everyone can hope to match Nelson's presidential collection, but Americans with any sense of history occasionally hitch their wagon to a presidential moment.

Members of the Greatest Generation remember the sudden death of Franklin Roosevelt (who was serving his fourth term), baby boomers can tell you where they were when they heard Kennedy was assassinated, Gen-Xers may have the same memory about the attempted assassination of Reagan and millennials likely recall their feeling of pride when Barack Obama, the first black president, was inaugurated.

Leave it to the current vice president, Mike Pence, though, to sum up what the office means to many of us.

"The presidency," he said, "is the most visible thread that runs through the tapestry of the American government. More often than not, for good or for ill, it sets the tone for the other branches and spurs the expectations of the people."

Contact Clint Cooper at ccooper@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6497.