When did you first realize you were black?

"My mother was a principal in a two-room schoolhouse in Eufaula, Alabama," Dr. Everlena Holmes said. "We had to walk five miles to school to get there early to start the fire in the pot-belly stove."

This was second or third grade, 77 years ago. Today, Holmes, who lives in Glenwood, is retired - one the most active retirees in the city - yet that Eufaula memory remains present.

"White kids went by on the school bus and threw things at us," she said. "They had the school bus. We had to walk."

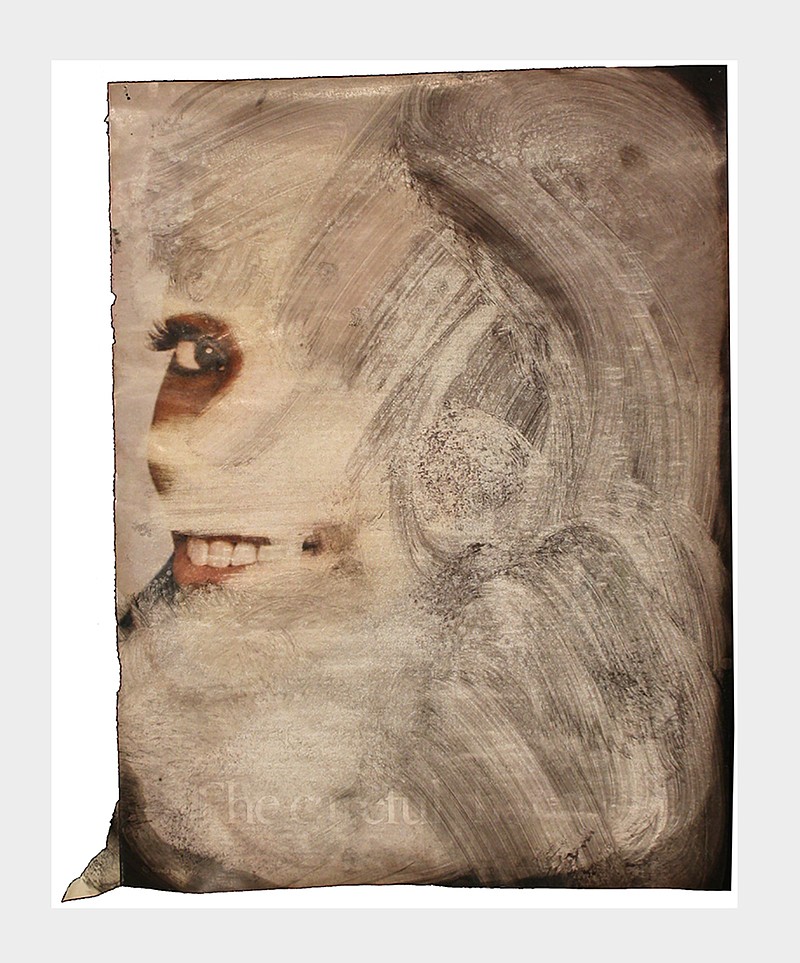

A few days ago, Holmes and I stood inside the Hunter Museum of American Art, taking in Noel W. Anderson's powerful exhibit "Blak Origin Moment." Anderson, Kentucky-born and Yale University-educated, is an African American whose body of work poses vital questions:

How are black bodies portrayed in the media?

How do those images shape our consciousness?

When did you first realize you were black?

"When did you learn you were different?" Holmes asked.

Her family left Eufaula for Tuskegee, where strong African American communities modeled critical thought, strength-in-numbers and abiding resilience; she became a university dean, then moved here a decade ago, sort of the civic equivalent of acquiring VW.

Holmes is unvanquished; her loving vision of human rights has produced a body of community work humbling to behold.

"There is a lot of hopelessness," she said. "We are going to have to turn the lights back on."

By the time we met at the Hunter, she'd attended two meetings with the city, trying to leverage power downward, not up.

"In a lot of communities, people feel like they're in prison," she said. "They don't feel safe. They don't feel free."

There in the Hunter, we stood before one large and arresting image - measuring more than 9 feet by 13 feet. Anderson created a black-and-white tapestry from a 1970s photo: black men lined up against the wall - feet apart, spread 'em - by police.

They are handcuffed.

"Shackled," Holmes said.

Their pants are pulled down, shirts off, in underwear only.

"This looks like the Hamilton County officers," I thought, "who stripped that man on the roadside car."

It is a tapestry, made of cotton.

"A different kind of plantation," Holmes said.

Yet it's no ordinary photo; Anderson manipulated it. Bodies are wavy, disfigured, legs bent backward and bodies forward; no human stands in such ways.

That's the point.

The images we see do not always tell the truth.

"Many media images of black men are linked to criminality or poverty, and positive depictions are often limited to sports and music," reports the Perception Institute. "One study of local news coverage found that black people are disproportionately portrayed as criminals, while white people are more often shown as the victims of crime."

"This is an exercise in perspective alteration," Anderson has said of his work.

In "Escapism," Anderson merged the faces of three black men killed by police and interposed each onto the face of their police shooter.

In another tapestry, Anderson manipulates the photograph of a prison scene. Black men are lined up - feet apart, spread 'em - against a prison fence. A white guard holds a shotgun; another white man takes a photograph.

The tapestry is not hung in a normal, four-straight corners way; only two or three points are fixed to the wall, creating these undulating W-shaped up-and-down lines.

More distortion.

To us, it looked like a ship.

"A slave ship," Holmes said.

We stayed there, talking and looking.

I asked Holmes to the exhibit so her voice could infuse this column.

This does not mean mine should hide.

I, too, must confront these distortions; as a white man, I must those confront the school kids on the bus, the abusive police, the distorted media images.

My white body must be examined, too.

Not to induce nebulous guilt, but to call forth responsibility and understanding.

I must gain an altered perspective.

How?

Over the course of her life, Holmes has been a Census volunteer five times: in New York, Arkansas, California, Alabama and Tennessee.

She's knocked on doors, homes, apartments, shotgun shacks, homeless camps in the deep woods.

Confederate flag houses. Barking Southern dogs. Holmes, possibly the only black woman for miles, walks up to them all, going places her cohorts won't.

There in the Hunter, with distorted images all around us, she remembered these moments.

Thousands of door-knocks. Thousands of strangers.

All of it ... good.

"I've never had a problem," she said.

Get to know one another.

Get past the distortions.

"You have to trust people," she said.

On Thursday, Jan. 9, the Hunter hosts a free healing service with African American leaders; it's from 6-7 p.m. The Anderson exhibit ends three days later on Jan. 12.

View other columns by David Cook

David Cook writes a Sunday column and can be reached at dcook@timesfreepress.com.