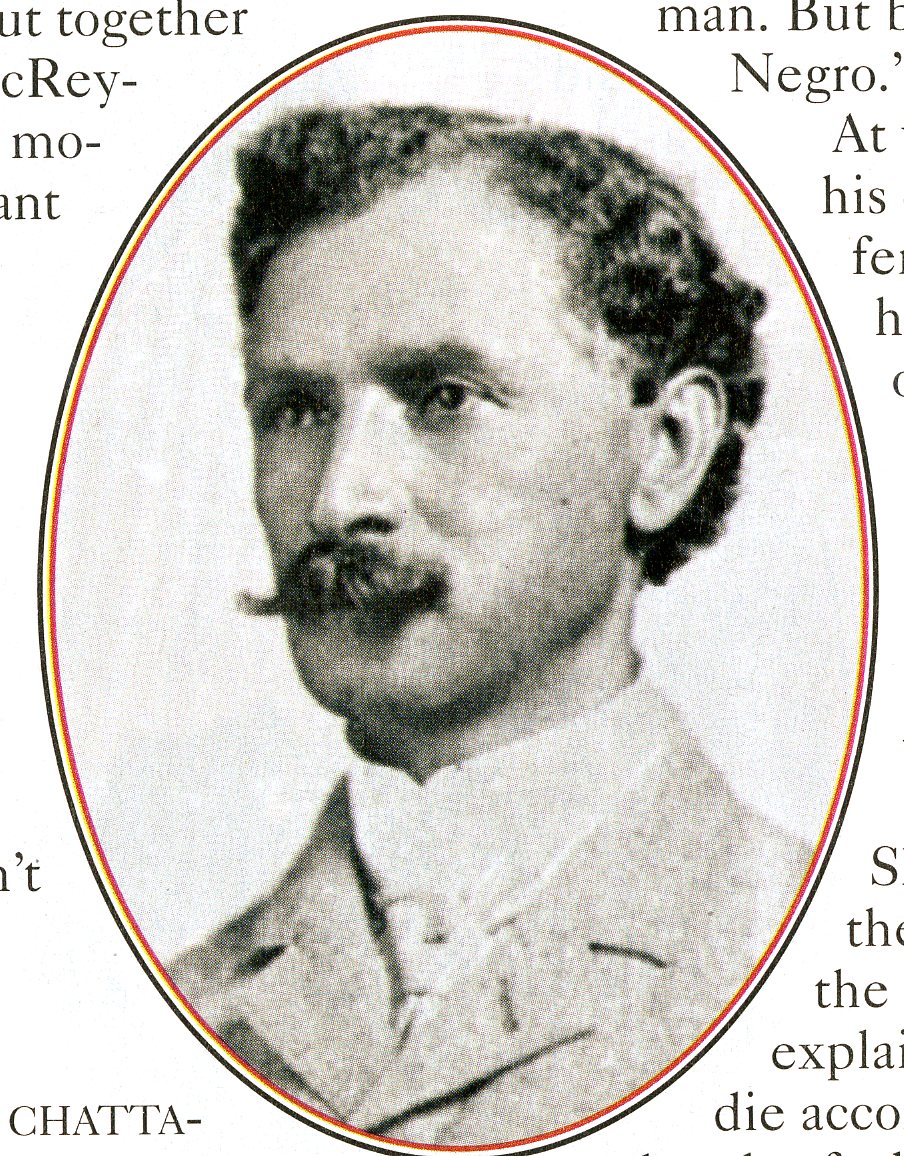

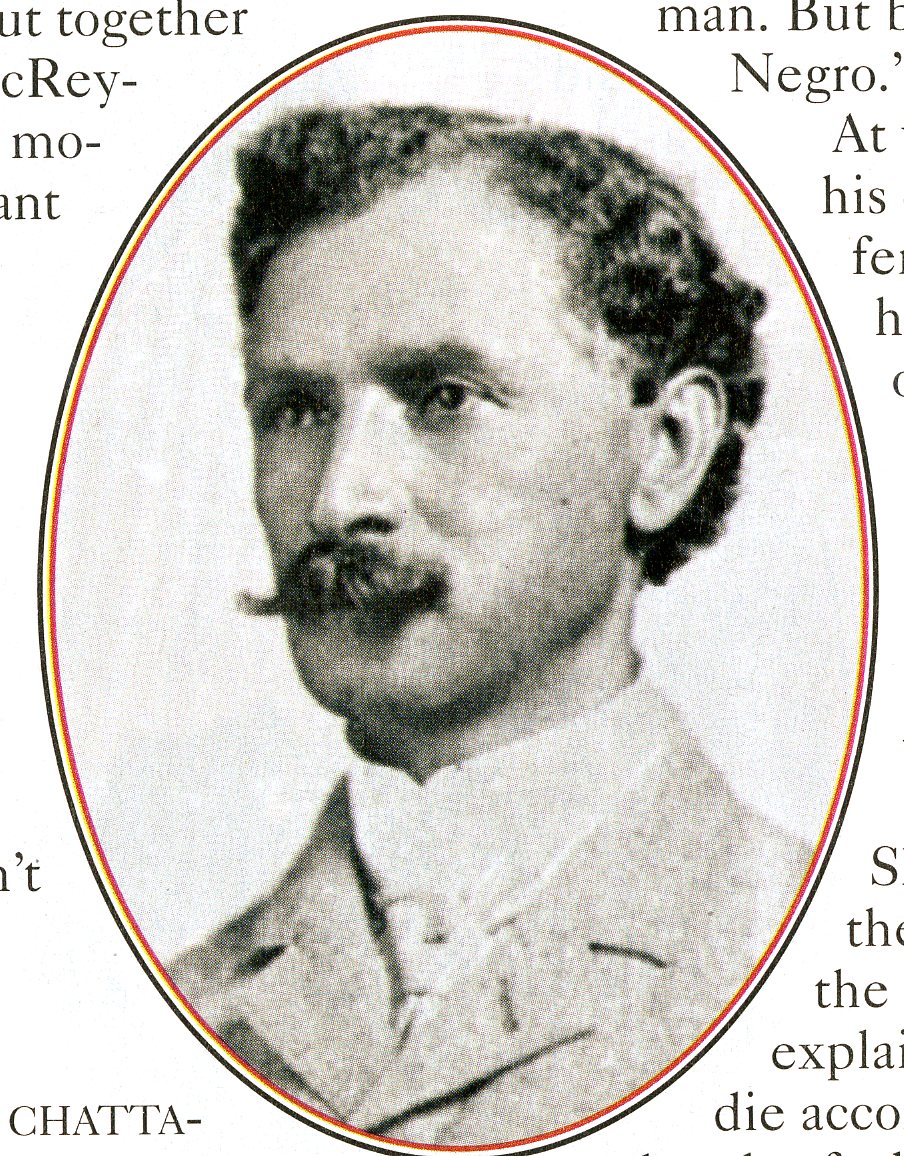

Styles Hutchins practiced law in Chattanooga at the turn of the century.

Styles Hutchins practiced law in Chattanooga at the turn of the century.

Editor's note: First of two parts. Read the second part here.

Born in Lawrenceville, Georgia, in 1852, Styles Hutchins did not lead the life of a typical black man in the years after the Civil War. His father, a wealthy artist, sent him to the private black Atlanta University. Upon graduation, Hutchins began a teaching career and in 1871 was named principal of the Knox Institute, a private black school in Athens, Georgia.

An ambitious young man, he resigned his position in 1873 and entered the University of South Carolina School of Law. After graduation, he was admitted to practice before the South Carolina Supreme Court. For a time he served as a judge but resigned following the Democratic Party's return to power and departed for Atlanta.

Seeking admission to practice law in Georgia, he was subject to an 1875 state law requiring lawyers to pass an examination by the presiding judge. The white judge publicly declared the admission of "a Negro upon social professional equality with white men was an innovation hardly to be tolerated."

Hutchins fought back and after a six-month struggle became the first African American admitted to the Georgia Bar. He reportedly tired of the racial atmosphere in Georgia and in 1881 moved to Chattanooga, where he opened a law practice.

Ever eager for a challenge, Hutchins in 1882 entered into a partnership with other black leaders to establish The Independent Age, the first newspaper in Chattanooga owned and operated solely by African American men. Hutchins was the first editor. Using the newspaper as a platform, he entered politics as a Republican and in 1886 was elected to the Tennessee State Legislature. A follower of W.E.B. DuBois, Hutchins' speeches and writings attacked whites who would deny the rights of black people.

He served one term and returned to the practice of law in 1888. Remaining active in politics, he wrote a letter that year to The Chattanooga Times endorsing Democrat Grover Cleveland for president, stating white Republicans "did not now care whether he (the Negro) is protected or not."

Hutchins was ordained a minister by the United Brethren in Christ church in 1901. Styles Hutchins loved to preach, and his fiery style in the pulpit made him a popular figure. He had a wife and children, but little is otherwise known of his family.

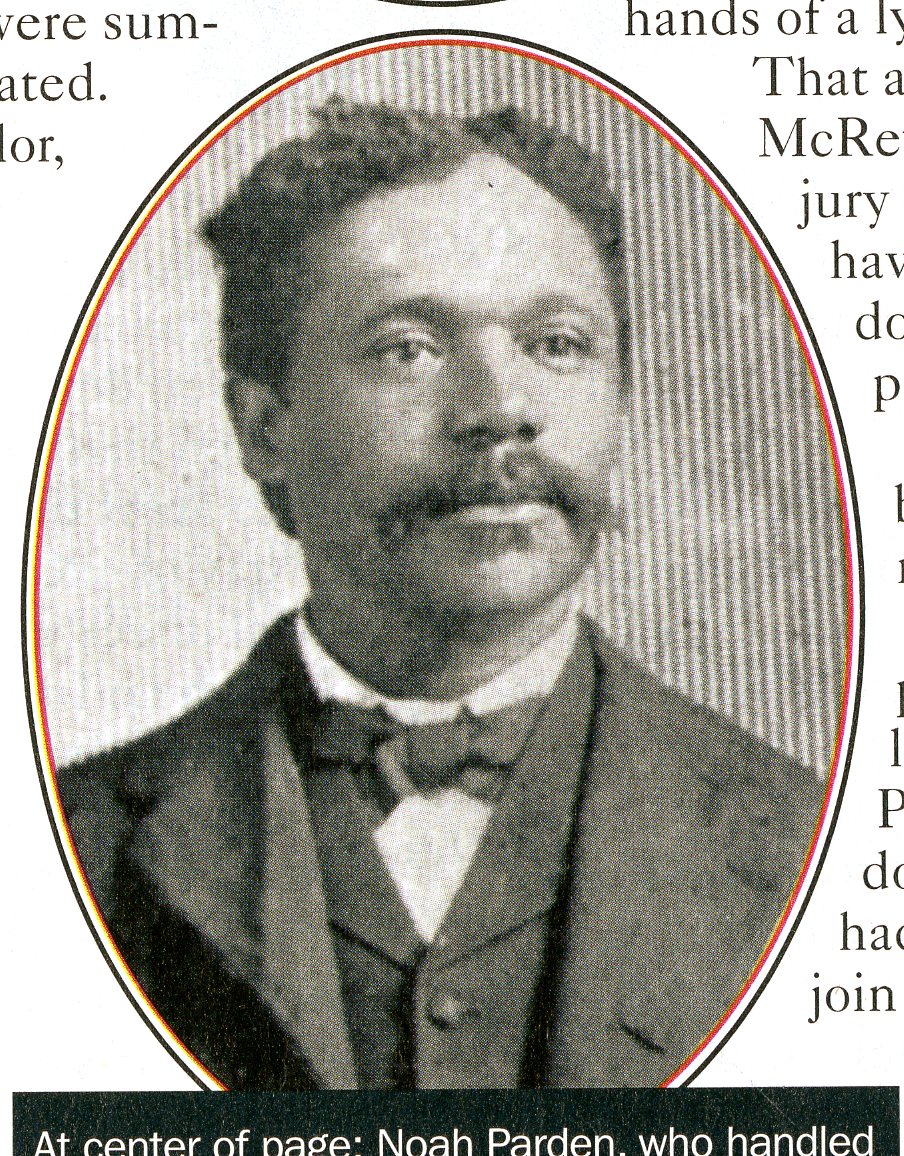

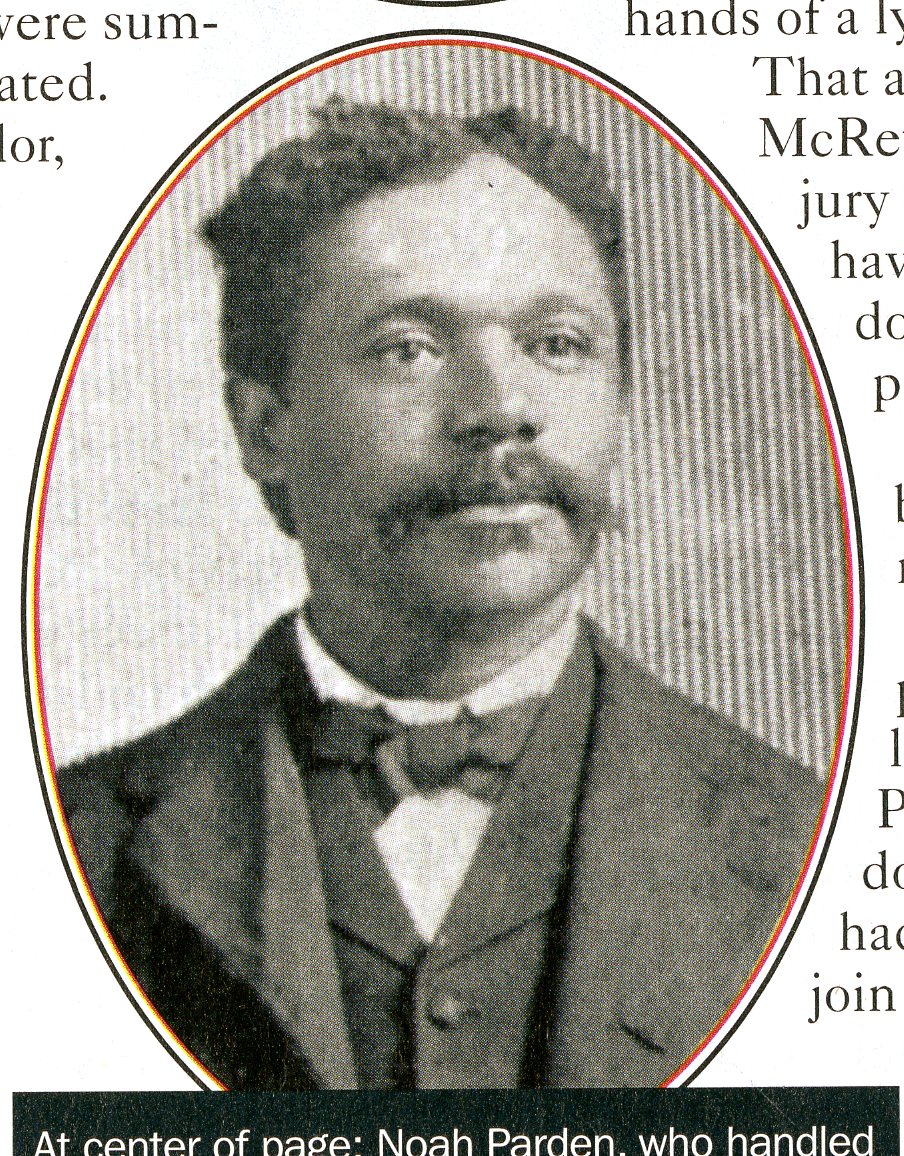

Norah Parden practiced law in Chattanooga at the turn of the century.

Norah Parden practiced law in Chattanooga at the turn of the century.

Norah Parden was born near Rome, Georgia, in 1868. His mother was a former slave who worked as a cook and housekeeper. His father was an unidentified white man. His mother died when he was 7, and young Noah was sent to an orphanage.

At age 16, Parden settled in Chattanooga. For five years, he supported himself as a barber and a carpenter while attending Howard High School. During his 1890 graduation, he presented the class oration, "The Duty of a Citizen." Parden enrolled as a senior in the law department of Central Tennessee College in Nashville. Graduating at the top of his class in 1891, he returned to Chattanooga and opened a law practice with another black attorney, James Easley. The two published a newspaper, The Chattanooga Herald. Later Parden joined Hutchins at The Independent Age.

Parden married Mattie Broyles of Dalton, Georgia, in 1892. The couple had two children, Frank and Lillian.

By the turn of the century, Parden had a successful law practice with a reputation as an effective defense attorney able to obtain victories for his African American clients as they faced all-white juries.

On Jan. 23, 1906, Nevada Taylor, a 21-year-old white woman, left her bookkeeping job at Brooks Grocery on Market Street. Taking one of the new electric trolleys, she arrived in St. Elmo across the street from the Lookout Mountain Incline and walked toward the house on the Forest Hills Cemetery grounds that she shared with her father, cemetery Superintendent William Taylor, and her brother. Near the cemetery gates she was attacked from behind by a man who choked her with a leather strap. She was thrown over a wall, raped and left unconscious.

Three days later, Ed Johnson, a 24-year-old black man, was arrested and charged with the rape of Taylor.

Johnson's trail, lynching, and the resulting Supreme Court case forever linked Styles Hutchins and Norah Parden to this tragic event.

Gay Moore is the author of numerous articles and two books, "Chattanooga's St Elmo" and "Chattanooga' Forest Hills Cemetery." Contact her at gaymoore@comcast.net. For more visit chattahistoricalassoc.org.

Read more Chattanooga History Columns

- Gaston: Paul John Kruesi was Edison's right-hand man

- Robbins: The old Richardson's house and the Civil War

- Gaston: James Williams was a man of the world

- Raney: Mason Evans, the 'Wild Man of the Chilhowee'

- Gaston: The legacy of Adolph Ochs endures

- Martin: Ed Johnson said, 'I have a changed heart,' the day before his lynching in Chattanooga on 1906

- Thomas: The inventiveness of Judge Michael M. Allison

- Moore: Chattanooga's first Chinese community

- Summers, Robbins: Chattanooga's Tuskegee Airman - Joseph C. White

- McCallie: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says so!

- Gaston: John McCline's Civil War - from slave to D.C. parade

- Raney: Exploring Chattanooga businesses in the Green Book

- Elliott: Remembering the Freedmen's Bureau in Chattanooga

- Gaston: Nancy Ward was a beloved, respected Tennessean

- Martin: Prohibition - the noble experiment

- Elliott: 'A shameful, disgraceful deed': The destruction of the Sewanee cornerstone

- Gaston: Robert Cravens was ironmaster, Chattanooga area's first commuter

- Robbins: Dr. T.H. McCallie's Christmas 1863

- Robbins: Journalist writes of a trip to Missionary Ridge in 1896

- Summers, Robbins: Mine 21 disaster - gone but not forgotten

- Elliott: Collegedale incorporates to avoid Sunday 'blue laws'

- Gaston: 'Marse Henry' Watterson's journalism fame began in Chattanooga

- Robbins: Orchard Knob battle recalled in 1895

- Elliott: Chattanoogans joined in an 'orgy of joy and gladness' on Armistice Day, 1918

- Thomas: Noted service, speakers are marks of Rotary Club of Chattanooga since 1914

- Summers and Robbins: Remembering noted Tennessee author North Callahan

- Raney: 'I auto cry, I auto laugh, I auto sign my autograph'

- Gaston: Sequoyah's alphabet enriched Cherokees

- Robbins: A look at Sam Divine's life during the Civil War

- Robbins: Memories of a Confederate nurse

- Robbins: More notes from Bradford Torrey's 1895 visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Robbins: Journalist in 1895 details visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Elliott: Telephone exchange firebombing was distraction for grocery store robbery

- Gaston: Worcester brought Christ's message to Cherokee at Brainerd Mission

- Robbins: 1896 travel diary: 'A Week on Walden's Ridge'

- Gaston: Elizabeth Strayhorn, WAC Commandant at Fort Oglethorpe

- Robbins: The history of the Friends of Moccasin Bend National Park

- Moore: Do you own a Sears Roebuck home?

- Summers and Robbins: Camp Nathan Bedford Forrest in World War II

- Gaston: Hiram Sanborn Chamberlain remembered

- Elliott: Daisy the center of tile, ceramic manufacturing in Hamilton County

- Gaston: FDR inaugurates the Chickamauga Dam

- Summers, Robbins: Interned WWII Germans had it easy at Camp Crossville

- Elliott: A war correspondent on Lookout Mountain

- Gaston: Chickamaugas finally bury hatchet in Tennessee Valley

- Gaston: Chickamaugas in Chattanooga

- Robbins: The history of the Riverbend festival

- Raney: Sadie Watson, the first woman elected in Hamilton County government

- Moore: Remembering Chattanooga's Hawkinsville community

- Elliott: Welsh coal miners transformed Soddy after the Civil War

- Gaston: Chattanooga's best-kept secret

- Elliott: Cabell Breckinridge loses his horse

- Raney: Martin Fleming is the people's judge

- Gaston: The amazing career of Francis Lynde

- Martin: Hamilton County's Name Sake: Alexander Hamilton

- Summers, Robbins: The crosses at Sewanee

- Bledsoe: The fiery truce at Kennesaw Mountain

- Moore: Talented architect's life cut short by tragedy

- Rydell: Chattanooga's place in soccer history

- Robbins: Tennessee Coal, member of the First Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Raney: In the barber chair

- Lanier: Becoming the Boyce Station Neighborhood Association

- McCallie: John P. Franklin: Living history among us

- Barr: Chattanooga's first railroad: The Underground Railroad

- Summers, Robbins: Charles Bartlett was a Pulitzer Prize winner, Kennedy confidant

- Rainey: 'We have seen it'

- Elliott: Feinting and fighting at Running Water Creek and Johnson's Crook

- Gaston: The Spring Frog Cabin at Audubon Acres

- Raney: Wauhatchie Pike was moonshine motorway

- Robbins: Oakmont was home of venerable Williams clan

- Summers and Robbins: Rebirth of the Mountain Goat Line

- Elliott: Bad investments led to Soddy Bank failure in 1930

- Summers and Robbins: Pearl Harbor attack left football behind

- Gaston: Jolly’s Island namesake had long ties with Sam Houston

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Indian Agent

- Moore: Did you know about St. Elmo's other two cemeteries?

- Summers: Orme - Marion County's almost lost community

- Davis: Spooky revival at Sharp Mountain in 1873

- Robbins: The story of Longholm

- Raney: Women labored to help the U.S. win World War I

- Even in the city, the 'wheel' changed everything

- Murray: Confederate dilemma after Chickamauga

- J.B. Collins — Newsman extraordinaire

- Robbins: The Story of the Lyndhurst Mansion

- Chattanooga artist and wife lost on the Lusitania

- Chattanooga History Column: Battelle, Alabama and the Battelle Institute

- John Ross, a founder of Chattanooga

- Hamilton County casualties in World War I

- Chattanooga Power Couple

- 'Somewhere in France'

- The Ray Moss family

- Battery B from Chattanooga

- Ulysses S. Grant, Clark B. Lagow, and the Chattanooga Bender

- Songbirds Museum Timeline

- Hamilton County World War 1 roster

- The Soddy Girl and the Memphis Belle

- Blues icon Bessie Smith was the Empress of Soul

- Women's Army Corps at Chickamauga

- Emma Bell Miles' life at the top of the 'W'

- The Tivoli Wurlitzer is one of Chattanooga's priceless assets

- Chattanooga in struggle for freedom during Civil War

- October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic

- Eli Lilly and the Ditch of Death

- One hundred years ago, Chattanooga goes to war

- The legacy of Anna Safley Houston

- Harriet Whiteside was ahead of her time

- Southern Adventist University

- Chattanooga native's writings aided Civil Rights movement

- Zion College, Chattanooga's only African American College

- The North Shore's hidden past

- Mayme Martin -- Businesswoman and community leader

- Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom

- Top of Cameron Hill was price of rerouting interstate

- Cameron Hill has rich history

- Temperance movement included Harriman university

- The sweetest music this side of Heaven

- Conquistadors at Chattanooga

- Chattanooga and the 'General'

- Chattanooga's first Thanksgiving, 1863

- Chattanooga's greatest flood caught city unaware

- Opening the Cracker Line

- European trip in 1900 enlightens Sophia Scholze Long

- Sophia Scholze Long spoke out when others were silent

- Little South Pittsburg and its big silent movie stars

- Lot attendant recalls hottest job in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's Forest Hills is final resting place for known, unknown

- Burritt College -- Pioneer of the Cumberlands

- Chattanooga's nicknames trace city's evolution

- The 25th annual meeting of the Tennessee Press Association

- Clemons Brothers Furniture Store

- The Short Life of the USS Chattanooga

- Ellen Jarnagin McCallie lived a truly remarkable life

- Dr. Jonathan Bachman was a revered city father

- Second guessing the Confederate failure on Missionary Ridge

- Nancy Kefauver, ambassador for the arts

- William Gibbs McAdoo kept his Southern roots

- Chattanooga's Secretary of the Treasury

- Howard Baker remembered as a statesman/photographer who snapped history

- Tivoli's last picture show

- The history of one of Chattanooga's oldest businesses

- Chattanooga's roller derby skaters

- Myths of Coca-Cola in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's neighborhood grocery stores

- The tale of the Scottsboro Boys

- The people's history of Chattanooga

- Howard School is Chattanooga's reminder of Reconstruction

- Elevator operator, painter, mystery man: meet Rice Carothers

- Raulston Schoolfield made enemies amid his rise to power

- Website lets users peer into Chattanooga's past

- The flood of 1917

- Chattanooga's 'wickedest woman' buried at Forest Hills

- History of Cummings Highway