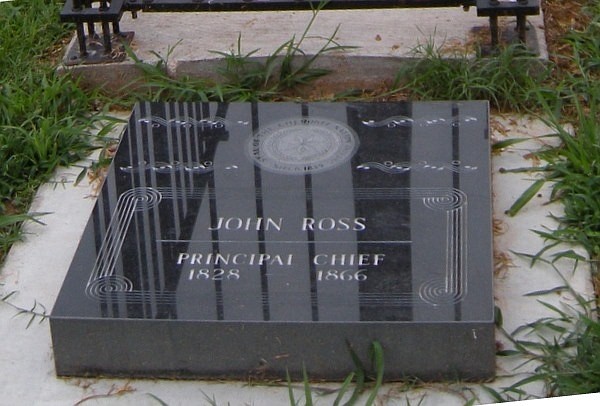

If the Cherokee Nation's future seemed perilous in late 1834, it was about to take a disastrous turn in 1835. While Chief John Ross and his delegation had been in Washington, D.C., once again attempting to persuade President Andrew Jackson to honor former commitment to the Nation, the situation was intensifying in Georgia.

When Ross would return home in early 1835, he would find a white family entrenched in his Georgia home, having purchased it during the Georgia lottery for the Cherokee lands. It's difficult to imagine Ross's shock as he rode into the yard after midnight and knocked on his door only to be faced by a new owner who announced that he had no idea where Ross's "Indian wife and children might have gone." After looking around and taking the lateness of the night into account, the owner invited him to spend the night but charged him for stabling his horse. The next day Ross tracked down his family and relocated them to a new home on Cherokee land in Tennessee.

Conditions would only worsen - and worsen quickly. When Ross attempted to move the Cherokee printing press from New Echota to Tennessee, it was seized by the Georgia Guard. When in the fall of 1835, Ross continued his protests against the actions of the Georgia Guard, surprise nighttime visitors would seize Ross at his Tennessee cabin with the announcement that "you are to consider yourself a prisoner." When Chief John Ross asked upon whose authority he was being arrested and for what charges, the leader of the Guard responded, "You'll know soon enough."

When Tennesseans realized that Georgia "militia" had invaded Tennessee to seize a legal resident, angry demands that Tennessee protect its sovereignty reached Tennessee's governor. The governor wrote to his Georgia counterpart demanding Ross's release or face the possibility of a "Tennessee paramilitary force of its own." Georgia's governor claimed to have no knowledge of the arrest of Ross but Ross would be released by late November. During his captivity, Ross had ascertained that the Georgia Guard was not operating under a directive from their governor but instead had been commanded into action by one of President Jackson's allies, Maj. Benjamin F. Currey. The removal plot had thickened.

The Georgians and the federal government began negotiations with the rival Cherokee leadership group, led by Major Ridge. While Ridge predicted that he might be killed for signing a removal treaty, it appears that, despite his own economic gain, Ridge believed that his people's future would only be guaranteed by accepting the inevitable and moving west for a new beginning. The treaty would be signed at New Echota on Dec. 29 at Elias Boudinot's home, allocating $5 million to the Cherokee along with other generous provisions for a school fund, payment for personal homes, food supplies and more. But on closer examination, those funds for provisions would be deducted from the $5 million, meaning the Cherokees would receive much less than they had been promised.

What about the Cherokee people's leader, Chief John Ross? As preparations for the removal began, Ross and 32 other Cherokee leaders met at Red Clay, Tennessee, and signed a letter declaring that the treaty was "a fraud upon the government of the United States and an act of oppression on the Cherokee people." Ross sent the letter to President Jackson, who read it and announced that it was "disrespectful" to the president and Congress.

The letter was returned to Ross with an admonition that removal was to begin. Military leaders, loyal to their president, offered observations about the difficulty of removing a nation opposing its relocation by noting a fear of the "shedding of human blood."

As others prepared for the journey, Ross traveled one last time to Washington, D.C., only to find the new president, Martin Van Buren, dealing with a financial panic and having little interest in the Cherokee plight. A final negotiation with the War Department raised the amount of money to be paid to $6 million dollars and the emigration would be funded by the government, not the army. It was Ross's final attempt to improve the conditions of the removal.

Ross's last days in the East were spent with one of the last parties to leave for the west, containing more than 1,600 of his people. They would depart from Blythe's Ferry. The roads and rivers ahead would be filled with tears.

Linda Moss Mines is the Chattanooga-Hamilton County historian, a member of the Tennessee Historical Commission and Regent, Chief John Ross Chapter, NSDAR.

Read more Chattanooga History Columns

- Gaston: Paul John Kruesi was Edison's right-hand man

- Robbins: The old Richardson's house and the Civil War

- Gaston: James Williams was a man of the world

- Raney: Mason Evans, the 'Wild Man of the Chilhowee'

- Gaston: The legacy of Adolph Ochs endures

- Martin: Ed Johnson said, 'I have a changed heart,' the day before his lynching in Chattanooga on 1906

- Thomas: The inventiveness of Judge Michael M. Allison

- Moore: Chattanooga's first Chinese community

- Summers, Robbins: Chattanooga's Tuskegee Airman - Joseph C. White

- McCallie: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says so!

- Gaston: John McCline's Civil War - from slave to D.C. parade

- Raney: Exploring Chattanooga businesses in the Green Book

- Elliott: Remembering the Freedmen's Bureau in Chattanooga

- Gaston: Nancy Ward was a beloved, respected Tennessean

- Martin: Prohibition - the noble experiment

- Elliott: 'A shameful, disgraceful deed': The destruction of the Sewanee cornerstone

- Gaston: Robert Cravens was ironmaster, Chattanooga area's first commuter

- Robbins: Dr. T.H. McCallie's Christmas 1863

- Robbins: Journalist writes of a trip to Missionary Ridge in 1896

- Summers, Robbins: Mine 21 disaster - gone but not forgotten

- Elliott: Collegedale incorporates to avoid Sunday 'blue laws'

- Gaston: 'Marse Henry' Watterson's journalism fame began in Chattanooga

- Robbins: Orchard Knob battle recalled in 1895

- Elliott: Chattanoogans joined in an 'orgy of joy and gladness' on Armistice Day, 1918

- Thomas: Noted service, speakers are marks of Rotary Club of Chattanooga since 1914

- Summers and Robbins: Remembering noted Tennessee author North Callahan

- Raney: 'I auto cry, I auto laugh, I auto sign my autograph'

- Gaston: Sequoyah's alphabet enriched Cherokees

- Robbins: A look at Sam Divine's life during the Civil War

- Robbins: Memories of a Confederate nurse

- Robbins: More notes from Bradford Torrey's 1895 visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Robbins: Journalist in 1895 details visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Elliott: Telephone exchange firebombing was distraction for grocery store robbery

- Gaston: Worcester brought Christ's message to Cherokee at Brainerd Mission

- Robbins: 1896 travel diary: 'A Week on Walden's Ridge'

- Gaston: Elizabeth Strayhorn, WAC Commandant at Fort Oglethorpe

- Robbins: The history of the Friends of Moccasin Bend National Park

- Moore: Do you own a Sears Roebuck home?

- Summers and Robbins: Camp Nathan Bedford Forrest in World War II

- Gaston: Hiram Sanborn Chamberlain remembered

- Elliott: Daisy the center of tile, ceramic manufacturing in Hamilton County

- Gaston: FDR inaugurates the Chickamauga Dam

- Summers, Robbins: Interned WWII Germans had it easy at Camp Crossville

- Elliott: A war correspondent on Lookout Mountain

- Gaston: Chickamaugas finally bury hatchet in Tennessee Valley

- Gaston: Chickamaugas in Chattanooga

- Robbins: The history of the Riverbend festival

- Raney: Sadie Watson, the first woman elected in Hamilton County government

- Moore: Remembering Chattanooga's Hawkinsville community

- Elliott: Welsh coal miners transformed Soddy after the Civil War

- Gaston: Chattanooga's best-kept secret

- Elliott: Cabell Breckinridge loses his horse

- Raney: Martin Fleming is the people's judge

- Gaston: The amazing career of Francis Lynde

- Martin: Hamilton County's Name Sake: Alexander Hamilton

- Summers, Robbins: The crosses at Sewanee

- Bledsoe: The fiery truce at Kennesaw Mountain

- Moore: Talented architect's life cut short by tragedy

- Rydell: Chattanooga's place in soccer history

- Robbins: Tennessee Coal, member of the First Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Raney: In the barber chair

- Lanier: Becoming the Boyce Station Neighborhood Association

- McCallie: John P. Franklin: Living history among us

- Barr: Chattanooga's first railroad: The Underground Railroad

- Summers, Robbins: Charles Bartlett was a Pulitzer Prize winner, Kennedy confidant

- Rainey: 'We have seen it'

- Elliott: Feinting and fighting at Running Water Creek and Johnson's Crook

- Gaston: The Spring Frog Cabin at Audubon Acres

- Raney: Wauhatchie Pike was moonshine motorway

- Robbins: Oakmont was home of venerable Williams clan

- Summers and Robbins: Rebirth of the Mountain Goat Line

- Elliott: Bad investments led to Soddy Bank failure in 1930

- Summers and Robbins: Pearl Harbor attack left football behind

- Gaston: Jolly’s Island namesake had long ties with Sam Houston

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Indian Agent

- Moore: Did you know about St. Elmo's other two cemeteries?

- Summers: Orme - Marion County's almost lost community

- Davis: Spooky revival at Sharp Mountain in 1873

- Robbins: The story of Longholm

- Raney: Women labored to help the U.S. win World War I

- Even in the city, the 'wheel' changed everything

- Murray: Confederate dilemma after Chickamauga

- J.B. Collins — Newsman extraordinaire

- Robbins: The Story of the Lyndhurst Mansion

- Chattanooga artist and wife lost on the Lusitania

- Chattanooga History Column: Battelle, Alabama and the Battelle Institute

- John Ross, a founder of Chattanooga

- Hamilton County casualties in World War I

- Chattanooga Power Couple

- 'Somewhere in France'

- The Ray Moss family

- Battery B from Chattanooga

- Ulysses S. Grant, Clark B. Lagow, and the Chattanooga Bender

- Songbirds Museum Timeline

- Hamilton County World War 1 roster

- The Soddy Girl and the Memphis Belle

- Blues icon Bessie Smith was the Empress of Soul

- Women's Army Corps at Chickamauga

- Emma Bell Miles' life at the top of the 'W'

- The Tivoli Wurlitzer is one of Chattanooga's priceless assets

- Chattanooga in struggle for freedom during Civil War

- October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic

- Eli Lilly and the Ditch of Death

- One hundred years ago, Chattanooga goes to war

- The legacy of Anna Safley Houston

- Harriet Whiteside was ahead of her time

- Southern Adventist University

- Chattanooga native's writings aided Civil Rights movement

- Zion College, Chattanooga's only African American College

- The North Shore's hidden past

- Mayme Martin -- Businesswoman and community leader

- Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom

- Top of Cameron Hill was price of rerouting interstate

- Cameron Hill has rich history

- Temperance movement included Harriman university

- The sweetest music this side of Heaven

- Conquistadors at Chattanooga

- Chattanooga and the 'General'

- Chattanooga's first Thanksgiving, 1863

- Chattanooga's greatest flood caught city unaware

- Opening the Cracker Line

- European trip in 1900 enlightens Sophia Scholze Long

- Sophia Scholze Long spoke out when others were silent

- Little South Pittsburg and its big silent movie stars

- Lot attendant recalls hottest job in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's Forest Hills is final resting place for known, unknown

- Burritt College -- Pioneer of the Cumberlands

- Chattanooga's nicknames trace city's evolution

- The 25th annual meeting of the Tennessee Press Association

- Clemons Brothers Furniture Store

- The Short Life of the USS Chattanooga

- Ellen Jarnagin McCallie lived a truly remarkable life

- Dr. Jonathan Bachman was a revered city father

- Second guessing the Confederate failure on Missionary Ridge

- Nancy Kefauver, ambassador for the arts

- William Gibbs McAdoo kept his Southern roots

- Chattanooga's Secretary of the Treasury

- Howard Baker remembered as a statesman/photographer who snapped history

- Tivoli's last picture show

- The history of one of Chattanooga's oldest businesses

- Chattanooga's roller derby skaters

- Myths of Coca-Cola in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's neighborhood grocery stores

- The tale of the Scottsboro Boys

- The people's history of Chattanooga

- Howard School is Chattanooga's reminder of Reconstruction

- Elevator operator, painter, mystery man: meet Rice Carothers

- Raulston Schoolfield made enemies amid his rise to power

- Website lets users peer into Chattanooga's past

- The flood of 1917

- Chattanooga's 'wickedest woman' buried at Forest Hills

- History of Cummings Highway