The March day I walked into the Chattanooga News-Free Press building looking for a job as a copy boy in 1968 was very different from the day I retired from the Chattanooga Times Free Press earlier this year.

Over a half-century, production and personalities constantly changed. There were both challenges and fun times while putting the latest and most accurate news into the homes and hands of thousands of readers – and taking pride in a business very much in the public eye.

At age 20 I was on furlough from the University of Chattanooga. I had lost my student job. I had bought my first car. I needed money. The afternoon paper needed a copy boy. (Read gopher.) The Youth Opportunity Center connected us.

The editor doing the hiring was Charlie Crane. The Coopers and the Cranes once lived three doors apart, so I had an entrée. He started me the next day.

The job was to circulate around the newsroom all day, collecting stories on paper, sending them up a chute to the union printers in the composing room one floor above and then distributing galley proofs sent back down the chute to various editors and reporters. When the press sprang into action with the first edition, I distributed papers "hot off the press'' to every desk in every office and to all the writers and editors.

Immediately, I fell in love with the urgency and excitement of the deadline-driven newsroom, the clacking sound of two dozen teletype machines, the barking of orders by people, like tough City Editor Bill Hagan, and seeing a fresh display of current events roll off the press every day about 11:10 a.m. Even the Typographical Union's composing room full of Linotype machines spitting out one line of type at a time of cooling hot lead had its charm.

Martin Luther King was assassinated three weeks after I was hired. Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated three months after my hiring. The newsroom took on an urgent tone in getting comprehensive information ready for publishing. Our jobs seemed very important. Much later, the Challenger explosion, the Waco Branch Davidian mass killings, the Jim Jones cult mass killings in Guyana, and certainly 9/11 would similarly put news professionals in high gear.

The six-days-per-week job took me every day into founder and Publisher Roy McDonald's office where he sat behind a desk so heavily laden it looked like a small mountain, but he knew where everything was. With a watch on a fob in his shirt pocket and always wearing a white shirt, he peered over his glasses to all comers, often while punching his huge, old-fashioned calculator. "Mr. Roy,'' as even the newest employee was supposed to call him, had the weight of hundreds of employees on his shoulders amidst an expensive war with the morning Chattanooga Times. At the same time he was chairman of the board of BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee that he had founded years earlier. His door was always open.

In an adjoining office was Lee Anderson, the wise, mild-mannered editor-in-chief, and Mr. Roy's son-in-law. He arrived each morning at 6 a.m. on the dot and within one hour cranked out five editorials, seven days a week, using a manual Royal typewriter he pounded with three fingers. He could type faster than I could think. He was involved in almost every good civic endeavor throughout the city and received, over time, numerous awards given by local and national organizations. In addition to writing, he served as managing editor. Over the years Lee became my Sunday school teacher and the most influential person in my life outside of family.

A number of Mr. Roy's children, grandchildren, sisters and other kin played roles at the paper over time. Quite a few employees throughout the building - a former hosiery mill on Eleventh Street - had come from the Home Stores grocery chain which Mr. Roy had owned, but had sold to fuel the paper in its battle against extinction. It was by any measure a family newspaper. And I liked that.

Newsroom of personalities

The newsroom was full of characters. One reporter typed with a cigarette between his fingers, leaving a pile of ashes a half-inch thick under his keyboard. A man in the sports department always had a cigar going. He never drove a car, walking to work from his home at the YMCA. Another reporter had only a few teeth, but they held the cigarettes that were always present. An editor delivered mail between gathering news, always with the stump of a cigar smoldering twixt his lips. Many others also contributed to the smoky room of years ago, so typical in newspaper lore. A seemingly straight-laced reporter thought he fooled his colleagues by secretly smoking only in a men's room stall. He was sorely embarrassed one morning when he found a note in his cigarette pack that said, "Everyone knows what you're doing.''

Legendary City Hall reporter J.B. Collins, now 102, would rush back down Eleventh Street to bang out the latest city government news, often being interrupted by calls from a mayor, commissioners or other City Hall source. Photographer George Moody was a friend to just about every fireman and police officer in town. They regularly called him about arrests or fires, resulting in the Free Press often getting spot news photos that the competition missed.

Business Editor Pete McCall loved covering ribbon-cuttings but didn't particularly enjoy covering strikes. When he went to Washington, D.C., as a congressman's press aide, eager, hustling John Vass took on Chattanooga's business world and conquered it. Another reporter went halfway around the world for an important story, but John Barleycorn almost kept him from writing that story on his return.

Automotive Editor Buddy Houts kept all of us in stitches with his antics in the newsroom, in his humorous columns and in his frequent calls to on-the-air broadcaster Luther Masingill. He often substituted other people's mugs at the top of his column as a joke. One Saturday night before Easter Sunday, Buddy ran a comic picture of a bunny rabbit where Buddy's photo would usually run. No-nonsense press foreman Skinny Owens came to the newsroom after the bulldog edition had run to question the bunny picture. We told him that was just Buddy fooling around, as usual. Skinny went trudging back to the pressroom saying, "This place is going to --.'' More about Skinny a little later.

Elderly Church Editor Hilda Spence was everybody's favorite. She lovingly took good care of copy brought in by all the preachers in town. When she planned her retirement, a feature story was written about her for the upcoming Easter Sunday. But she died that weekend; the story became a sidebar to her obituary.

The arts critic drew most of the male reporters' attention when she sashayed through the city room. One sports reporter had a temper. Once he was so angry he just shoved his typewriter off his desk and onto the floor. And one of the married newsmen frequently carried on phone conversations with his lady friend.

There were and are many other newsroom characters and dramas, but only a book could tell all the stories.

On the beat

When news was breaking that the University of Chattanooga was going to become a campus of the University of Tennessee, I attended a gathering where UC President William Masterson would address affected students. Just on a lark, this copy boy wrote an unsolicited story about that meeting. The next morning I showed it to the city editor and he recommended it as a sidebar to the main merger story. My first byline was on Page One!

Just a few years after my arrival at the paper, the contract with the typographical union ran out and negotiations with the printers' union had not been resolved. To be prepared for the possibility of a strike and to prepare for more modern printing, new "cold type'' machinery that spat out stories on paper was purchased to get around the need for the centuries-old hot lead method of printing, and a number of us trained behind locked doors to be ready to print if necessary.

That day happened on Jan. 24, 1972. As a boisterous picket line formed outside, that Monday's edition was produced inside by us novices. The union knew we could produce pages, so they convinced the pressmen to go out in sympathy, figuring we couldn't get those pages printed. But foreman Skinny and Pig, a man I never knew except by that nickname, were loyal to Mr. Roy. They instructed a few others in the building who had some mechanical ability how to help, and the press rolled the first day of that strike. The union knew then that it was all over, but picketed for five years. We scabs were cursed day in and day out, newspaper racks around town were destroyed, BB's were sling-shotted from a nearby hill to dent employees' cars, and acid was thrown on some of our vehicles, mine included.

Years earlier, 1942 wartime economies had made it reasonable for the morning Times and the afternoon News-Free Press to form a joint operating agreement (JOA). All departments would be merged except the actual news departments. By the mid '60s, the afternoon News Free-Press sought to separate from the morning Times in the first dissolution of a JOA in American history. From 1966 until 1970, the morning Times brought out an afternoon paper - The Chattanooga Post - as direct competition to the News-Free Press. When I was covering the fire and police beat in 1969 and '70, the Post had a very tenacious police reporter, who, I regret, scooped me from time to time. Not a happy memory.

Money was tight in those competitive days. A number of executives mortgaged their homes to make payroll. I had been buying common stock since day one. When I wanted to purchase my first house, the paymaster in the business office was not at all happy when I asked to cash in that stock. Things were that tight. All the while, lucrative liquor ads and "dirty movie" ads were kept out of the family newspaper. But the afternoon and Sunday paper attracted many subscribers because of the use of color photos, which the competition in those days did not have.

When Lee Anderson recalled the provisions of the Taft-Hartley law, the paper took its case of predatory pricing to the Justice Department. The government found for the News-Free Press on Feb. 24, 1970, and the Post was vanquished in the settlement. A check for $2.5 million dollars in punitive damages came to Mr. Roy that many of us got to hold in our much-relieved hands. In subsequent years it was again deemed reasonable to have a new JOA, but this time all operations were in the News-Free Press building, except for the Times news department.

Elvis Presley had a big impact on the evening newspaper. When he died in August 1977, we had a big section on his career the next Sunday. The papers sold out and more had to be printed. The public ate it up. So the next Sunday we came out with Elvis II. Once again, it sold out. On the third and fourth Sundays, we had Elvis III and IV. I was given the assignment to lay out those four sections. The wonderful upshot was that many Elvis lovers started subscribing, giving the biggest period of new sales in the paper's history.

Onto the copy desk

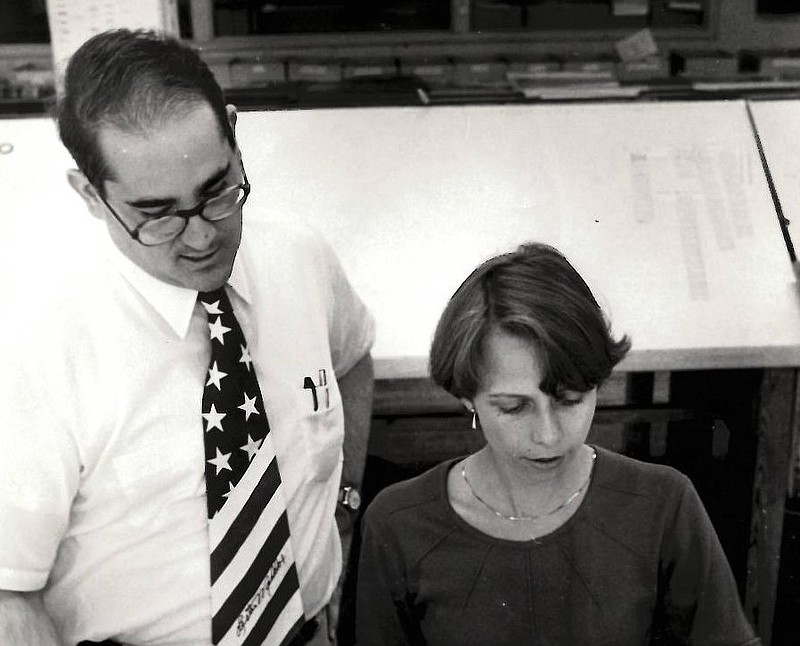

I joined the copy desk crew in 1972 as a copy editor. Our task was to edit news copy, write headlines, select photos to run with stories and proofread the pages of each day's first edition. We worked on a horseshoe-shaped desk. The news editor sat inside the horseshoe making story selections and giving orders. The "rim rats'' sat on the outside of the horseshoe. That went on for a number of years. First we used manual typewriters, then electric typewriters whose copy could be read by a new computer scanner. As time went by, modern computers were purchased, then later versions and even later versions were employed. Those were tough learning-curve periods with each update.

During President Ronald Reagan's years in office, he would invite editors of supportive papers to come to the nation's capital for press briefings, rather than hosting the usual Washington press corps. Mr. Anderson was invited several times, once sitting next to the president. In 1985, news editors were invited. Our head news editor was in the hospital, so I got the assignment to take his place. Lee gave me a new title to take along - associate news editor.

Secretaries of State and Defense met with us in the Old Executive Office Building. Then we were walked to the White House next door for lunch with the president in the State Dining Room. Each table was hosted by a cabinet secretary or other high official. Chief of Staff Don Regan was to my immediate left. Making small talk, he asked what the biggest cash crop was in Tennessee at that time. "Marijuana,'' I told him, to laughter all around the table. I'm sure he expected me to say tobacco, corn, cotton or soybeans, but just a few days before, it had been reported that marijuana indeed brought in more money than any other crop that year.

The fancy tables had monogrammed china, finger bowls, engraved menus as well as engraved boxes of matches. We were served chicken picatta. Ever since, I order that dish when I see it at a restaurant. After the luncheon in those pre-9/11 days, we were turned loose on our own to leave the president's mansion. I passed a guard at the door, sauntered down the semi-circular driveway, passed a guard shack, crossed Pennsylvania Avenue and strolled into LaFayette Park, heading back to my hotel to write stories for the next day's editions.

Suddenly, I realized my reporter's notebook was not with me. My career was dependent on that notebook. There was nothing to do but try to get back in the White House and find it. I told my story to the man in the guard shack. He let me go forward unescorted. I got to the guard at the door. He said to go on in – unescorted! I walked to the State Dining Room where butlers were clearing tables. The man clearing my table said to check the butler's pantry. Venturing there alone, I found the notebook. Again, unescorted, I wandered back down the hall to the door, passed the first guard, then the second one and headed back to the hotel to write. Today that would never happen.

In the '80s and '90s, the travel editor got many offers to visit distant lands and attractions for publicity purposes. Meanwhile, the entertainment editor was invited to movie advance previews that included interviews with the actors. When those editors were swamped with offers, I was invited to take some of those trips. Hawaii and France were my favorite destinations. The films "Platoon'' (that won best picture in 1986) and "Big'' (including a chat with Tom Hanks) were standouts.

Mr. Roy was very generous and supportive of his people. When I planned to write the history of First Presbyterian Church in 1990, he said, "Do it first class. If it makes money after expenses, it's yours. If it doesn't, I'll absorb the costs.'' Fortunately it did pay for itself with just a little to spare. Lee Anderson was my proofreader.

Changes are coming

In 1993, the paper's look underwent a major makeover and its original name was returned - Chattanooga Free Press. Mr. Roy bought out the competitive News in 1939 and merged the name with Free Press. Journalism schools used to snicker that the News-Free Press name made it sound as if it were "free of news.'' One day when executives were huddled with a designer around a computer pondering a great variety of type styles for the remodeled paper's logo, I wandered by and made a suggestion that they liked and wound up using. It remains today only in the masthead on the Free Press editorial page

When longtime news editor and symphony trumpeter Stanton Palmer retired, I succeeded him at the helm of the copy desk of 10 men and women. It fell to me to either choose, or authorize, the stories that went on Page One. Ha! Arriving at 2:30 in the morning was the downside!

President Frank McDonald succeeded his father as chairman of the board in 1990. In just a few years, that "Dismembered Tennesseans'' member and spokesman was afflicted with Lou Gehrig's Disease. At the same time, other family executives were retirement age. They determined that it would be wise to sell the business.

The Free Press was courted by a number of news organizations, but executives chose to sell to the owner of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in Little Rock, led by Walter E. Hussman Jr. That was completed in March 1998. Little changed until the end of the year when it was revealed that Mr. Hussman was going to buy the morning Times as well and would merge the two longtime fierce competitors. Big change was coming. There would be no more working in the morning for an afternoon publication; a morning paper is put out in the evening. The merged paper first appeared on Jan. 5, 1999. Both staffs lost some members to reach the staffing number that made for an effective crew.

The Times' Rick Moore and I shared the news editor job for a year, and then I was named wire editor, daily sifting through stories from several wire services. Twenty-one years now after the merger, seven Times journalists remain in the newsroom, 15 remain from the Free Press, in addition to many later hires.

In the Great Recession, a number of newsroom folks, including myself, were laid off in 2009. After a stint in local tourism, I was rehired as a proofreader in 2013. Six-and-a-half years later, working complications borne of coronavirus distancing led me to decide it was time to hang up the job I loved for a half century.

One silver lining is that I went out as the longest serving of all current employees. Another silver lining is that my younger brother, Clint, who succeeded my mentor, Lee Anderson, as editor of the Free Press editorial page, continues at the paper plying his own excellent journalistic standards.

In the old days, when writers' stories ended, they concluded with what was known as a "30 dash''. So, I end my career with a ...

-30-

Email David Cooper at cannon55@epbfi.com