I asked a friend - she's Black - what John Lewis meant to her.

"Hope," she said.

To me, as a white man, John Lewis, the civil rights hero who died two weeks ago, meant something else.

I was born in 1974, so my first memories come from archives and history: grainy black and white documentaries of the young Lewis integrating lunch counters alongside Diane Nash, the Rev. Jim Lawson and other Fisk University students in downtown Nashville.

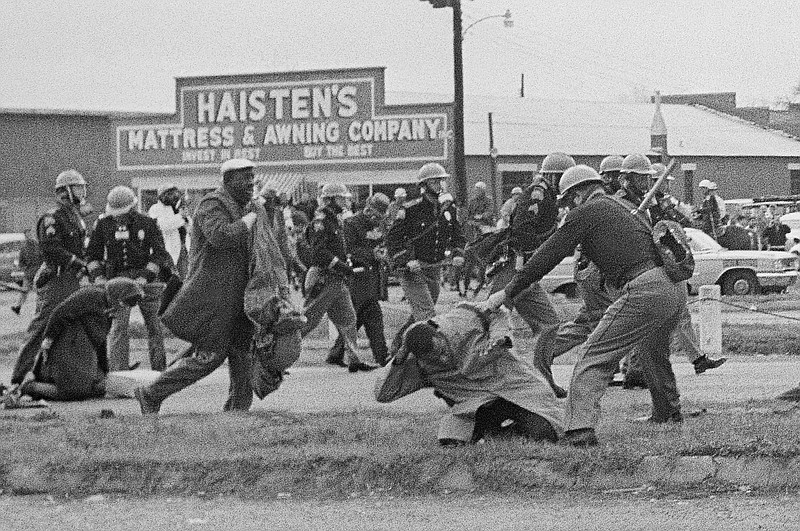

Film footage of the Selma Bridge crossing. The Freedom Rides. Arrest photos.

When I look at those old images and films, I'm drawn to him. Who wouldn't be? He was like an American Christ.

"He was wounded for America's transgressions, crushed for our iniquities and by his bruises we are healed," the Rev. Raphael Warnock, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, told the Associated Press.

Yet I am also drawn to the white people around him.

Punching, kicking, spitting, cursing, arresting, condemning, reviling, ridiculing, demeaning, insulting, ignoring, shoving, harassing.

It is critical to contemplate the life of John Lewis in days like this. His conscience. His nonviolent courage.

It is equally critical to examine his white enemies. Their cruelty. Their fear.

We as white people need to look hard.

Those are our people.

Those are our forefathers.

Today, I mourn John Lewis with two hearts: one awed by the nonviolent mountaintop he ascended. I loved him yet never even met him.

Yet another part of my heart is ashamed, humbled, repentant.

For white America, John Lewis did not represent hope.

He represented trouble.

A man we could not control.

John Lewis was a mirror.

He made white America face our own monstrosity.

He made us see, as James Baldwin called it, "the death of the heart."

Is that why we hated him so much?

Is that why we have always hated Black people so much?

Here's Baldwin again: "What white people have to do is try to find out in their hearts why it was necessary for them to have a n -- in the first place. Because I am not a n --. I'm a man. If I'm not the n -- here, and if you invented him, you the white people invented him, then you have to find out why."

What part of our whiteness invented racism?

What part of our whiteness clings, needs and wants racism?

Recently, I've had two separate conversations with Black Chattanoogans that end up at the same question.

"Do whites love each other?" they ask.

It's a haunting question.

Do we as white people really and truly love ourselves?

Racism - its demise or its continuation - depends on our answer to that question.

When we love, we refuse to dominate. Or exercise unjust power over others. We refuse to ignore.

When we love, we practice what is wholesome and healing.

Those racist white men? They can't punch and spit on John Lewis, then go home and love - genuinely, selflessly - their families, their neighbors, themselves. Such love would be stilted and incomplete; it may not even be love at all.

If we hate John Lewis, then we hate ourselves, too.

So if we learn to love ourselves - if we put down the knife of racism which cuts outward as well as inward, ruining the one who wields it - then, as Baldwin says, "the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed."

Look again at those old images.

Where does such cultivated hate come from?

My mind and heart are prone to judgment; how many steps away am I from such violence?

Where are the Selma Bridges of today? Who is being spat upon today?

Who are the John Lewises of Chattanooga?

Our answers can extend beyond race. John Lewis is alive every time a gay Chattanoogan refuses to silence his identity or her truth. I believe the gay closet is a segregated lunch counter of today.

John Lewis is alive every time we reject dogmatic and rigid definitions of one another. Nonviolent love always sees the best in people. It crosses the bridges fear erects.

John Lewis is alive every time we examine our minds and thoughts; that's where violence always begins.

John Lewis is alive every time we tell the truth in love.

"Though I may not be here with you," he wrote in a New York Times essay published after his death, "I urge you to answer the highest calling of your heart and stand up for what you truly believe. In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace, the way of love and nonviolence is the more excellent way. Now it is your turn to let freedom ring."

***

On Friday, Aug. 7, a revived Freedom Rides will appear in Chattanooga. Organized by the People's Uprising in Atlanta, some 17 buses and hundreds of people will arrive at 6:30 p.m. at Miller Park.

Called the Good Trouble Ride, the event honors Lewis with a goal of ending systemic oppression.

For more information on ways to help and be involved, email unitygroupchatt02@gmail.com.

David Cook writes a Sunday column and can be reached at dcook@timesfreepress.com.