This is Super Bowl Sunday, the apex of our American football season. (Chiefs by six.)

It is February, the start of Black History Month in Chattanooga.

This story merges the two.

In the early 1960s, Earl Alonzo Lee was a student at Howard High.

He was a guard on the football team.

And a young African American activist.

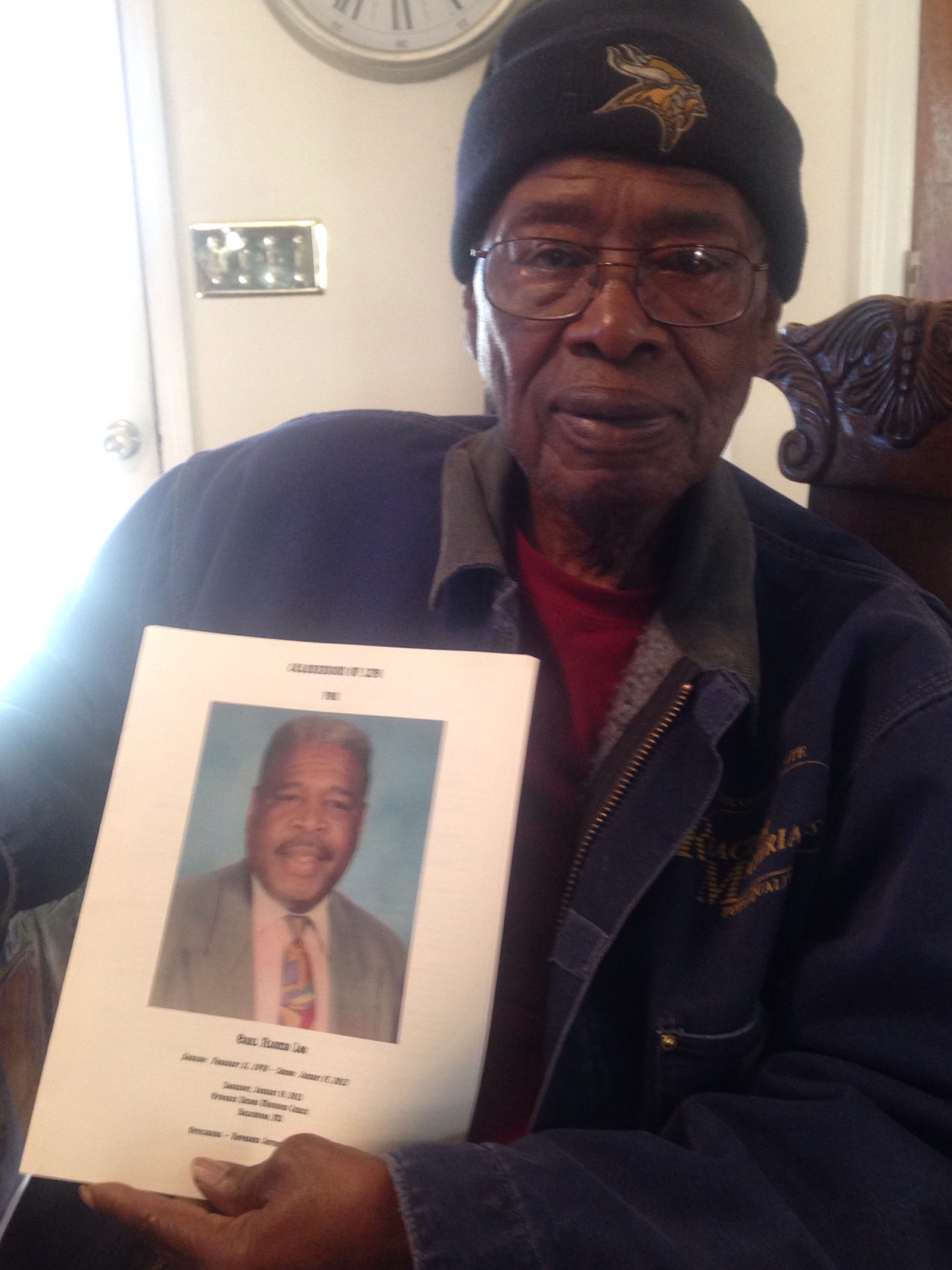

"He fought for the civil rights of blacks," said his older brother Marvin.

The Lee family lived in Poss Homes; their father made factory train brakes; their mother was a housewife. Racism was everywhere.

"You just don't know the half of it," Marvin said.

In 1960, Earl, Marvin and their two other brothers joined other Howard students in the downtown sit-ins. Did you know that Chattanooga was one of the first cities to use fire hoses on its black citizens?

("The chaos that erupted downtown prompted the police to become the first in the country to make use of fire hoses in crowd control," writes Jessie Harris in "Unfamiliar Streets: the Chattanooga Sit-ins, the Local Press and the Concern for Civilities.")

"God made us all the same," said Marvin, 80 and retired after a career at Mueller Company.

Soon after, Earl got the attention of the University of Wyoming; coaches offered him a football scholarship.

In the mid-'60s, Earl arrived in Laramie, Wyoming; 13 other black student-athletes joined the team.

"[They] were among the first few waves of black students on campus, and they often encountered white classmates from Wyoming who had only ever seen a black person on television. Students would ask to touch their hair, and one of the players was once asked by a classmate if he had a tail," write Wesley Lowery and Jacob Bogage of The Washington Post.

Playing on the road at Brigham Young University, "players spit on [one black player] and took cheap shots at his knees," the Post reports. "Referees, and even his own coach, had ignored his complaints about racist taunts. When Wyoming's black players walked back to the locker room after the game, someone turned on the field sprinklers, drenching them."

At the time, BYU also refused to ordain black students.

In October 1969, BYU was scheduled to play in Wyoming. The school's Black Student Union planned a protest.

Earl and his teammates had their own idea.

They'd each wear a black armband with a white "14" during the game.

"It was meant as a warning: if you mess with one of us, you've messed with all 14 of us," the Post reports.

They became known as the Black 14.

Needing permission, they went to talk to their coach. Within moments, he became enraged, and, according to the Post, "went into a racist diatribe."

On October 17, 1969, the day before the BYU game, the coach kicked them off the team.

"They were immediately banished," reports the Post, "sending many of their lives into turmoil."

Some left Wyoming, degree-less. NFL dreams vanished. The university, politicians, white fans, white teammates - they supported the coach.

The Black 14 became villains and outcasts.

Earl joined the Army, earned two degrees, then moved to Baltimore and built a career as public school educator and family man.

"My dad was a hard worker," said son Brian. "He was a very fun person to be around. And very smart."

For the rest of his life, Earl never spoke about Wyoming.

"It was hurtful. They were extremely hurt and extremely angry. They felt betrayed," said Brian. "Vilified."

In 2013, Earl, 66, died of heart disease, leaving behind Brian, wife Melissa and their two daughters, Lauren and Madison.

It was then Brian began learn of the Black 14. Books written, documentaries published.

Then, last fall, Brian got a phone call.

It was the University of Wyoming.

Fifty years after exiling the Black 14, university leaders were inviting them back.

They wanted to make things right.

"The University of Wyoming rolled out the red carpet for the Black 14 and did everything in their power to make amends," Brian.

In September, Brian joined eight living members of the Black 14 to return to the campus that once banished them. They spent days there, speaking on panels, talking with students. At a banquet dinner, university leaders made a reconciling statement.

"A letter of apology," said Brian.

Again and again, strangers approached Brian, saying the same thing: we're sorry.

On game day, Brian and the Black 14 members met with the team and coaches. Brian was given his dad's jersey and helmet.

"They then joined, arm-in-arm with current players, for the team's ceremonial "Cowboy Walk" march through the tailgate and into the stadium, and then, at halftime, were brought onto the field as the crowd roared," the Post reports.

"I can just imagine how much my dad would have loved to be a part of that," Brian said.

Earl's memory still lives - from here to Wyoming. The time is always right to do what is right.

After all, God made us all the same.

"Dad definitely stood on his principles," Brian said. "If something is not right and he has the ability to make it right, he will do what he can to make it right."

View other columns by David Cook

David Cook writes a Sunday column and can be reached at dcook@timesfreepress.com.