"Courage" is derived from the Latin word cor, which referred to the heart. Legendary second-century A.D. Roman physician, Galen, considered the heart as the source of the body's vitality and the seat of the soul.

By the time the word had migrated over centuries to Middle English it had become corage, the storehouse of the emotions. To speak with corage meant opening one's thoughts to the world. Today, courage means to confront danger, opposition or pain without showing fear.

Routinely, policemen exhibit courage as they confront uncertainties, which could rapidly escalate into violence. Each day, they protect the public from danger, whether in public or domestic surroundings. Firemen must have a reservoir of courage as they deal with the dangers of fire in homes, businesses and industry, and high-rise structures. Rescues are part of the challenge facing all first responders.

Members of the armed service may confront, with little warning, situations where multiple lives will be endangered by unexpected attacks in any environment.

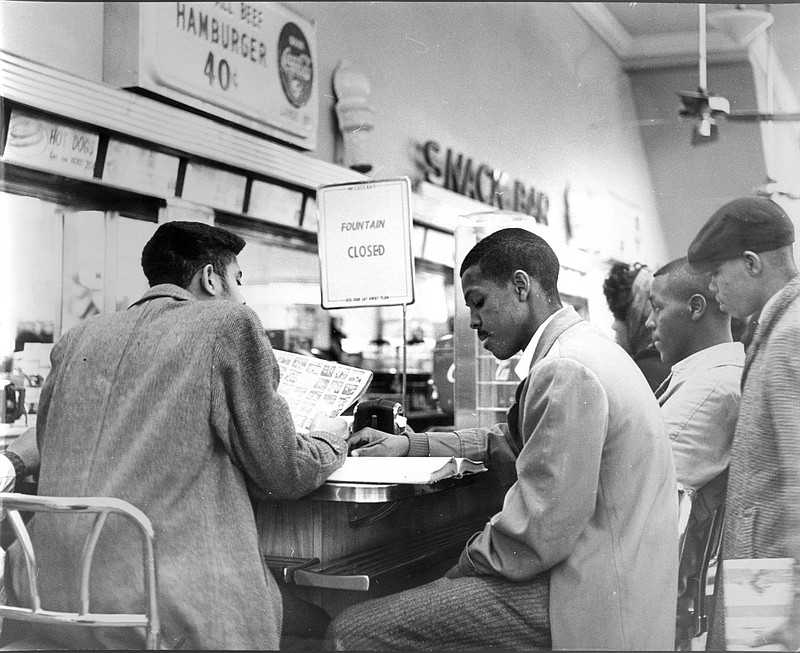

Courage of a different, quieter variety characterized the behavior of protesters who 60 years ago challenged segregation at our nation's lunch counters and other public facilities.

The protests began in Greensboro, North Carolina, on Feb. 1, 1960. when four African American students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University quietly took their seats at the lunch counter of a Woolworth's store. At that time, black customers could purchase food to take away. Service at the counter was limited to whites only. Refused service, the four remained seated until the store closed. Police appeared as did print and TV reporters. No arrests were made. The numbers of protesters grew daily as black and white students from other nearby colleges joined the ranks. By July, the Woolworth's store integrated its lunch counter.

Today, Greensboro's Civil Rights Center and Museum occupies the site of the former Woolworth's store. A restored lunch counter is a featured display.

Other sit-ins, led by college students, took place in Southern cities, sometimes with attacks on the peaceful protesters.

As news of the sit-ins reached Chattanooga, 12 African American, male students at Howard High School planned their protest. On Friday, Feb.19, 1960, they walked downtown from their school. Some took their seats at segregated lunch counters to order lunch. Refused service, they quietly remained seated. As their numbers increased over succeeding days, the students endured insults and threats and, on one occasion, dousing with firehoses outside the sites of their protests. Eventually, the students prevailed in the nation's first sit-in to be organized and led by high school students.

I had the privilege of knowing one of the protesters, Booker T. Scruggs II, a Howard senior in 1960. After earning undergraduate and graduate degrees from Clark University, Booker returned to his hometown. He served his community as director of Upward Bound at UT-Chattanooga. Twice, I participated in panels in sociology classes which he directed at the university. For many years, he hosted "Point of View," a program on public television that addressed a broad range of issues from politics to the arts to education. He had the remarkable ability to make people feel better, whatever the setting or occasion.

In his later years, he addressed serious illness with equanimity.

During the years in which I knew Booker, he never referred to his role in the sit-ins in Chattanooga. Only in 2010, when he and surviving members of the Howard High protesters were recognized at a community "heroes" luncheon did I learn of this singular act of courage.

In a subsequent conversation, he acknowledged that he had been afraid during the group's walk from school to the lunch counters. To him and his fellow protesters, segregated facilities represented a wrong that had to be addressed without further delay.

Quiet courage often goes unnoticed. Its practitioners find their reward in effecting change that benefits the lives of others.

Contact Clif Cleaveland at ccleaveland@timesfreepress.com.