Do you remember the moment in the Academy Award-winning movie, "Glory" when actor Denzel Washington grabbed the U.S. flag from the hands of the wounded flag bearer and led the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers forward? You probably held your breath as he scaled the ramparts after being wounded multiple times. Washington was portraying William H. Carney, the first African American Medal of Honor recipient. Sgt. Carney's true story is equally breathtaking in his display of valor.

Carney was born a slave in Virginia; his family moved to Massachusetts after gaining their freedom. Carney secretly learned to read and write, knowing that laws restricted blacks from educational improvement. He would later recall that, while God had called him to service in the church, he chose to serve God by joining the military and fighting to free those who were oppressed, using Moses as his inspiration.

He joined the Union Army and was assigned to Company C, 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry Regiment, the first official black unit recruited for the Union in the north, led by Col. Robert Shaw Gould. Forty other men of color served with Carney, including two of Frederick Douglass' sons. Citizens on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line questioned the value of "colored" troops, often speculating that during the heat of combat most would flee the field. Only months later, the 54th Regiment and Carney would prove those doubts unfounded while engaging in their first combat mission in South Carolina.

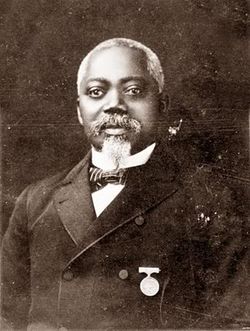

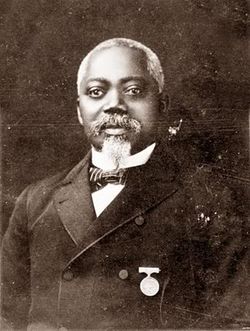

Sgt. William H. Carney in his older years. / Contributed photo

Sgt. William H. Carney in his older years. / Contributed photo

On July 18, 1863, Carney and his regiment led the charge on Fort Wagner. During intense fighting, the unit's color guard was shot. Carney, who witnessed the mortally wounded soldier stumble, scrambled to catch the falling flag.

In his own words, Carney recalled that day.

"When within about a thousand yards of the fort, we halted and lay flat on the ground waiting for the order to charge. The order came, and we had advanced but a short distance when we were opened upon with musketry, shell and canister, which mowed down our men right and left. When the color-bearer was disabled, I threw away my gun and seized the colors, making my way to the head of the column ... in less than twenty minutes I found myself alone struggling upon the ramparts, while all around me lay the dead and wounded ... The musket balls and grape shot were flying all around me ... I knew my position was a critical one All the men who had mounted the ramparts with me were either killed or wounded, I being the only one left erect and moving. Upon rising to determine my course to the rear, I was struck by a bullet, but, as I was not prostrated by the shot, I continued my course. I had not gone far, however, before I was struck by a second ball."

He would be wounded a third time before members of the 100th New York helped him to the rear. " ... my rescuer offered to carry the colors for me, but I refused to give them up, saying that no one but a member of my regiment should carry them."

While Carney's recollections, written decades later, create a sense of calm amidst a raging battle with tremendous casualties, the attack against Fort Wagner witnessed some of the highest casualties per troop numbers of any battle during the U.S. Civil War. In what became the high point of the battle, Carney recalled his return to his regiment, escorted by hospital corps. "When the men saw me bringing in the colors, they cheered me and I was able to tell them that the old flag had never touched the ground."

The courage demonstrated by the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry Regiment was carried by the Northern newspapers in detailed stories of the battle and by word-of-mouth across the entire nation. Among those who would later learn of Carney's commitment to save the Union colors was a young former slave in Williamson County, Tennessee, who would himself choose the military as a career.

On May 23, 1900, Sgt. William H. Carney would be awarded the Medal of Honor, the first African American to wear the medal. Carney's legacy reminds us that patriotism, sacrifice, courage and integrity are characteristics of all Medal of Honor recipients.

Next week, you meet Tennessean George Jordan, former slave, who will follow in Carney's footsteps.

Linda Moss Mines is vice president of education at the Coolidge National Medal of Honor Heritage Center and regent of the Chief John Ross Chapter, NSDAR.

Read more Chattanooga History Columns

- Gaston: Paul John Kruesi was Edison's right-hand man

- Robbins: The old Richardson's house and the Civil War

- Gaston: James Williams was a man of the world

- Raney: Mason Evans, the 'Wild Man of the Chilhowee'

- Gaston: The legacy of Adolph Ochs endures

- Martin: Ed Johnson said, 'I have a changed heart,' the day before his lynching in Chattanooga on 1906

- Thomas: The inventiveness of Judge Michael M. Allison

- Moore: Chattanooga's first Chinese community

- Summers, Robbins: Chattanooga's Tuskegee Airman - Joseph C. White

- McCallie: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says so!

- Gaston: John McCline's Civil War - from slave to D.C. parade

- Raney: Exploring Chattanooga businesses in the Green Book

- Elliott: Remembering the Freedmen's Bureau in Chattanooga

- Gaston: Nancy Ward was a beloved, respected Tennessean

- Martin: Prohibition - the noble experiment

- Elliott: 'A shameful, disgraceful deed': The destruction of the Sewanee cornerstone

- Gaston: Robert Cravens was ironmaster, Chattanooga area's first commuter

- Robbins: Dr. T.H. McCallie's Christmas 1863

- Robbins: Journalist writes of a trip to Missionary Ridge in 1896

- Summers, Robbins: Mine 21 disaster - gone but not forgotten

- Elliott: Collegedale incorporates to avoid Sunday 'blue laws'

- Gaston: 'Marse Henry' Watterson's journalism fame began in Chattanooga

- Robbins: Orchard Knob battle recalled in 1895

- Elliott: Chattanoogans joined in an 'orgy of joy and gladness' on Armistice Day, 1918

- Thomas: Noted service, speakers are marks of Rotary Club of Chattanooga since 1914

- Summers and Robbins: Remembering noted Tennessee author North Callahan

- Raney: 'I auto cry, I auto laugh, I auto sign my autograph'

- Gaston: Sequoyah's alphabet enriched Cherokees

- Robbins: A look at Sam Divine's life during the Civil War

- Robbins: Memories of a Confederate nurse

- Robbins: More notes from Bradford Torrey's 1895 visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Robbins: Journalist in 1895 details visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Elliott: Telephone exchange firebombing was distraction for grocery store robbery

- Gaston: Worcester brought Christ's message to Cherokee at Brainerd Mission

- Robbins: 1896 travel diary: 'A Week on Walden's Ridge'

- Gaston: Elizabeth Strayhorn, WAC Commandant at Fort Oglethorpe

- Robbins: The history of the Friends of Moccasin Bend National Park

- Moore: Do you own a Sears Roebuck home?

- Summers and Robbins: Camp Nathan Bedford Forrest in World War II

- Gaston: Hiram Sanborn Chamberlain remembered

- Elliott: Daisy the center of tile, ceramic manufacturing in Hamilton County

- Gaston: FDR inaugurates the Chickamauga Dam

- Summers, Robbins: Interned WWII Germans had it easy at Camp Crossville

- Elliott: A war correspondent on Lookout Mountain

- Gaston: Chickamaugas finally bury hatchet in Tennessee Valley

- Gaston: Chickamaugas in Chattanooga

- Robbins: The history of the Riverbend festival

- Raney: Sadie Watson, the first woman elected in Hamilton County government

- Moore: Remembering Chattanooga's Hawkinsville community

- Elliott: Welsh coal miners transformed Soddy after the Civil War

- Gaston: Chattanooga's best-kept secret

- Elliott: Cabell Breckinridge loses his horse

- Raney: Martin Fleming is the people's judge

- Gaston: The amazing career of Francis Lynde

- Martin: Hamilton County's Name Sake: Alexander Hamilton

- Summers, Robbins: The crosses at Sewanee

- Bledsoe: The fiery truce at Kennesaw Mountain

- Moore: Talented architect's life cut short by tragedy

- Rydell: Chattanooga's place in soccer history

- Robbins: Tennessee Coal, member of the First Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Raney: In the barber chair

- Lanier: Becoming the Boyce Station Neighborhood Association

- McCallie: John P. Franklin: Living history among us

- Barr: Chattanooga's first railroad: The Underground Railroad

- Summers, Robbins: Charles Bartlett was a Pulitzer Prize winner, Kennedy confidant

- Rainey: 'We have seen it'

- Elliott: Feinting and fighting at Running Water Creek and Johnson's Crook

- Gaston: The Spring Frog Cabin at Audubon Acres

- Raney: Wauhatchie Pike was moonshine motorway

- Robbins: Oakmont was home of venerable Williams clan

- Summers and Robbins: Rebirth of the Mountain Goat Line

- Elliott: Bad investments led to Soddy Bank failure in 1930

- Summers and Robbins: Pearl Harbor attack left football behind

- Gaston: Jolly’s Island namesake had long ties with Sam Houston

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Indian Agent

- Moore: Did you know about St. Elmo's other two cemeteries?

- Summers: Orme - Marion County's almost lost community

- Davis: Spooky revival at Sharp Mountain in 1873

- Robbins: The story of Longholm

- Raney: Women labored to help the U.S. win World War I

- Even in the city, the 'wheel' changed everything

- Murray: Confederate dilemma after Chickamauga

- J.B. Collins — Newsman extraordinaire

- Robbins: The Story of the Lyndhurst Mansion

- Chattanooga artist and wife lost on the Lusitania

- Chattanooga History Column: Battelle, Alabama and the Battelle Institute

- John Ross, a founder of Chattanooga

- Hamilton County casualties in World War I

- Chattanooga Power Couple

- 'Somewhere in France'

- The Ray Moss family

- Battery B from Chattanooga

- Ulysses S. Grant, Clark B. Lagow, and the Chattanooga Bender

- Songbirds Museum Timeline

- Hamilton County World War 1 roster

- The Soddy Girl and the Memphis Belle

- Blues icon Bessie Smith was the Empress of Soul

- Women's Army Corps at Chickamauga

- Emma Bell Miles' life at the top of the 'W'

- The Tivoli Wurlitzer is one of Chattanooga's priceless assets

- Chattanooga in struggle for freedom during Civil War

- October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic

- Eli Lilly and the Ditch of Death

- One hundred years ago, Chattanooga goes to war

- The legacy of Anna Safley Houston

- Harriet Whiteside was ahead of her time

- Southern Adventist University

- Chattanooga native's writings aided Civil Rights movement

- Zion College, Chattanooga's only African American College

- The North Shore's hidden past

- Mayme Martin -- Businesswoman and community leader

- Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom

- Top of Cameron Hill was price of rerouting interstate

- Cameron Hill has rich history

- Temperance movement included Harriman university

- The sweetest music this side of Heaven

- Conquistadors at Chattanooga

- Chattanooga and the 'General'

- Chattanooga's first Thanksgiving, 1863

- Chattanooga's greatest flood caught city unaware

- Opening the Cracker Line

- European trip in 1900 enlightens Sophia Scholze Long

- Sophia Scholze Long spoke out when others were silent

- Little South Pittsburg and its big silent movie stars

- Lot attendant recalls hottest job in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's Forest Hills is final resting place for known, unknown

- Burritt College -- Pioneer of the Cumberlands

- Chattanooga's nicknames trace city's evolution

- The 25th annual meeting of the Tennessee Press Association

- Clemons Brothers Furniture Store

- The Short Life of the USS Chattanooga

- Ellen Jarnagin McCallie lived a truly remarkable life

- Dr. Jonathan Bachman was a revered city father

- Second guessing the Confederate failure on Missionary Ridge

- Nancy Kefauver, ambassador for the arts

- William Gibbs McAdoo kept his Southern roots

- Chattanooga's Secretary of the Treasury

- Howard Baker remembered as a statesman/photographer who snapped history

- Tivoli's last picture show

- The history of one of Chattanooga's oldest businesses

- Chattanooga's roller derby skaters

- Myths of Coca-Cola in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's neighborhood grocery stores

- The tale of the Scottsboro Boys

- The people's history of Chattanooga

- Howard School is Chattanooga's reminder of Reconstruction

- Elevator operator, painter, mystery man: meet Rice Carothers

- Raulston Schoolfield made enemies amid his rise to power

- Website lets users peer into Chattanooga's past

- The flood of 1917

- Chattanooga's 'wickedest woman' buried at Forest Hills

- History of Cummings Highway