Chattanoogans have long felt that their beautiful and healthful climate was a barrier to diseases affecting Memphis, Nashville and New Orleans. Dr. James Redfield, a New York physician who came to the Cumberland Plateau in the 1850s, praised the benefits of its mountain climates in his letters. Yet, as Chattanooga became a thriving commercial metropolis, it experienced the disadvantages from that growth, arising from crowded populations, often living in unsanitary locations. In addition, the railroads brought business, people and diseases.

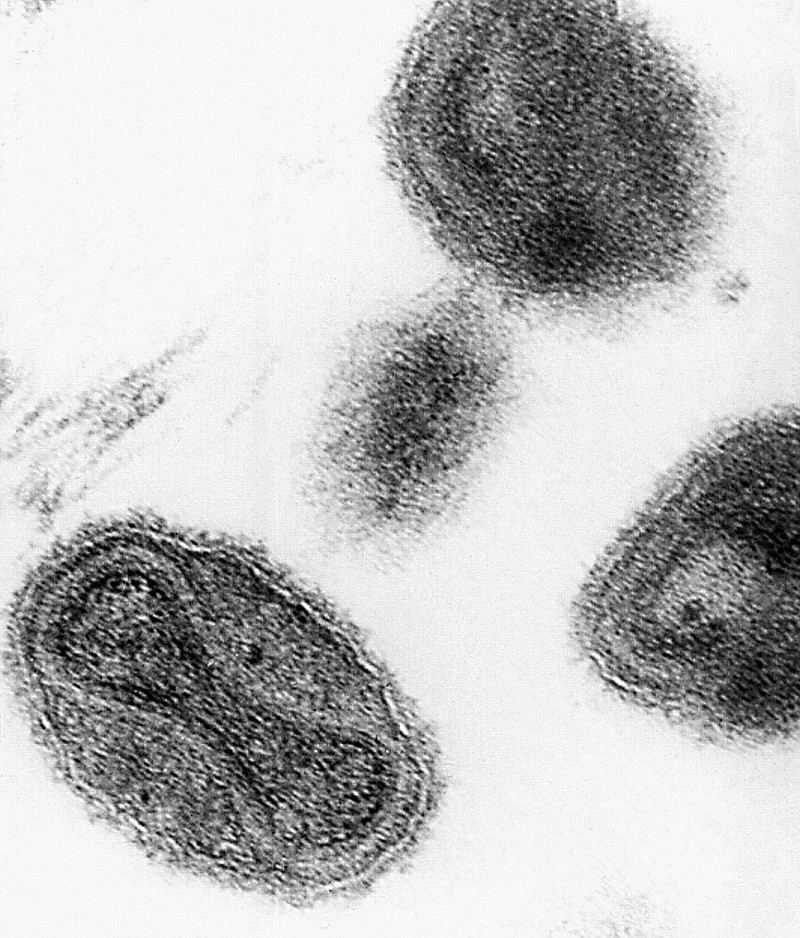

In November 1865, Chattanooga Mayor Richard Henderson and aldermen drafted resolutions reported in the Nov. 8, 1865, Chattanooga Daily Gazette, on the need to stop smallpox. Chattanooga's population had doubled, and many lived in dirty hovels on crowded, unclean streets. The resolutions called for dispersal of all "assemblages" in the city, any loiterers to be arrested or removed, and all homes to be thoroughly cleaned. Since many public buildings had been destroyed, officials also asked to use the outbuildings at the mouth of Citico Creek (near today's Lincoln Park) for a pest house to isolate cases.

Smallpox came to Chattanooga again in 1874 and killed 20 individuals. In 1882, anyone visiting the infected without permission was charged a misdemeanor. City physicians repeatedly demanded pesthouses, new sewers, clean privies and streets, and above all mandatory vaccinations. In 1884, city physician Dr. G.W. Drake required "compulsory vaccination of all the well ... isolation of the sick (in a pesthouse) ... disinfection of rooms, furniture, and clothing," thus virtually stamping out smallpox in Chattanooga. The U.S. experienced its last case in 1949.

The first case of what became the cholera epidemic came in 1873 with a brakeman on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. He had boarded the train ill with diarrhea and was "ready for his coffin" within a few hours. Mrs. Richards, who operated a boarding house for several railroad employees, next succumbed to the sickness. Cholera is a bacterial infection spread mostly by unsafe food and water that results in severe dehydration. Inhabitants of poor shanties living in lower marshy elevations with limited clean water died most quickly. Almost 2,000 Chattanoogans left the city for higher and healthier topography.

LEARN MORE

Dr. J.H. Van Deman’s reports on cholera and yellow fever can be found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

Dr. J.H. Van Deman, who was a surgeon during the Civil War and in charge of the hospital in Chattanooga, reported only five deaths "from the hills."

Town officials believed that eating fruits and vegetables caused the disease, calling it the "watermelon" cholera. Dr. Eli Wight, Chattanooga mayor, issued a proclamation forbidding produce sales. The final death toll was 102.

Dr. Van Deman summarized Chattanooga's cholera epidemic in his report "Cholera in Chattanooga ... During the Summer of 1873." Cholera continued to afflict the city until it had adequate sewer systems and clean water supplies. Dr. Van Deman's biography in the "1888 Sketches of Prominent Tennesseans" told that he "remained at his post" through three epidemics of smallpox, two of cholera and one of yellow fever.

River towns experienced several yellow fever outbreaks. In 1878, Chattanoogans rose up to organize aid for Memphis and other affected towns. Local officials did not initially examine or quarantine yellow fever refugees.

The first Chattanooga yellow fever case came with Memphis refugee Mrs. Swarzenberg, who died on Aug. 21, 1878. Others became ill, but the Board of Health deemed that Chattanoogans need not worry as the deaths were from "bilious remittent fever." Then in September came the deaths of young Arthur Burge, his mother and Mrs. Corey. These deaths prompted a citywide exodus to the surrounding mountains. Judge David Key and his family boarded their surrey for Walden's Ridge with unfinished laundry in hand. Only 1, 800 out of 11,484 Chattanooga residents would remain in the city during the worst of the epidemic.

By Sept. 28, the local Board of Health declared a yellow fever epidemic. A Yellow Fever Relief Committee headed by Elbert James organized the work in preparing for assistance for the ill and burial for the dead. Only a few businesses stayed open, the newspaper published a half-sheet, and trains were quarantined. Volunteers aiding the sick included ministers, schoolteachers, city officers and doctors. Harry Savage, Chattanooga's notorious gambler, redeemed himself by caring for orphans. Mayor Thomas Carlisle died on Oct. 29, one of the fever's last victims. The city registrar's November report listed 440 cases, including 140 deaths.

Chattanooga survived its 19th century epidemics and continued to prosper.

Contact Chattanooga Public Library archivist Suzette Raney at localhistory@lib.chattanooga.gov. For more visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org.