The reporting done on election night 2018 offers a cautionary tale for the news media as we approach Nov. 3.

Because more than a quarter of that year's 116 million votes were mailed, initial projections of the midterm results turned out to be wildly inaccurate. They showed Democrats making only modest gains in the House, far less than the historical average for the party not in the White House. As Jake Tapper announced on CNN that night, "This is not a blue wave."

Only when all the votes were counted, three weeks later, did Americans learn precisely how wrong that was. The Democrats prevailed by unprecedented margins and picked up many more seats (40 of them) than usual for the out party.

Now, with some 80 million mail-in ballots expected, accurately predicting winners before the count is complete looks to be even more perilous than two years ago. This is because millions of those envelopes will not even have been opened - let alone the contents tabulated - when the news anchors sign off the morning after Election Day.

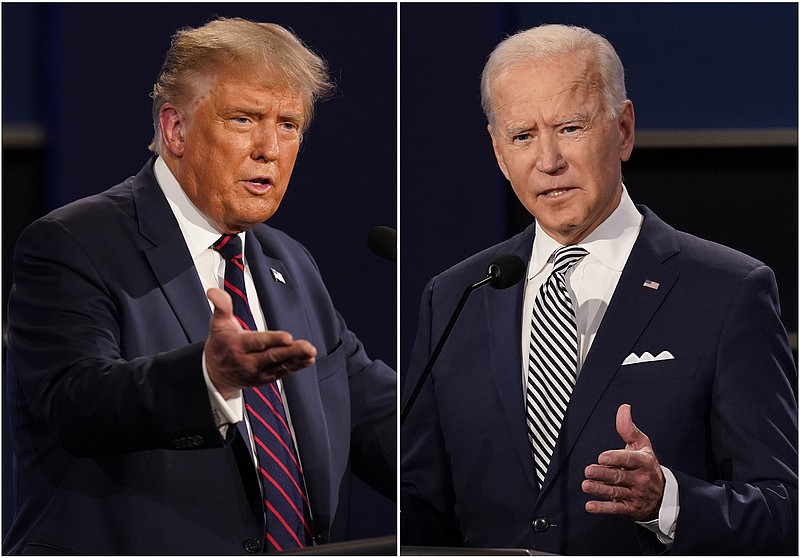

Absent the sort of landslide that polling doesn't now foresee, it may be many days before enough votes have been counted to make clear whether the winner is President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden.

As a result, we need new norms to govern what the media does two weeks from now.

All news media, especially cable and broadcast TV, must exercise restraint and avoid the customary scramble to be first to declare a victor. Such caution does not come naturally to many journalists or the organizations where they work. And it runs against the grain of a culture increasingly attuned to receiving instant information, even if it later turns out to be inaccurate.

Yet, for the country to have any chance of avoiding post-election chaos, it is crucial for the media to resist premature declarations.

This year, surveys suggest that those preferring Trump are more likely to cast their votes on Election Day while Biden backers will cast their ballots by mail. And so 2020, like 2018, is likely to see a "blue switch" as the mail gets opened.

Knowing this, news executives should marshal their self-discipline. They need to refrain from offering viewers the illusion of simultaneity, even if it means that they do not project a presidential victor on Nov. 3. At the very least, they should only declare a winner of a state once there are fewer outstanding votes than the official margin separating Trump and Biden.

As the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics notes, journalists in a democracy should never sacrifice accuracy for speed. They have a duty to "gather, update, and correct information throughout the life of a news story." That will never be more important, for our democracy, than in the weeks ahead.

Austin Sarat is associate provost, associate dean of the faculty and a professor of jurisprudence and political science at Amherst College.

The Fulcrum is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news platform covering efforts to fix our governing systems. It is a project of, but editorially independent from, Issue One.

Tribune Content Agency