This isn't really about the books.

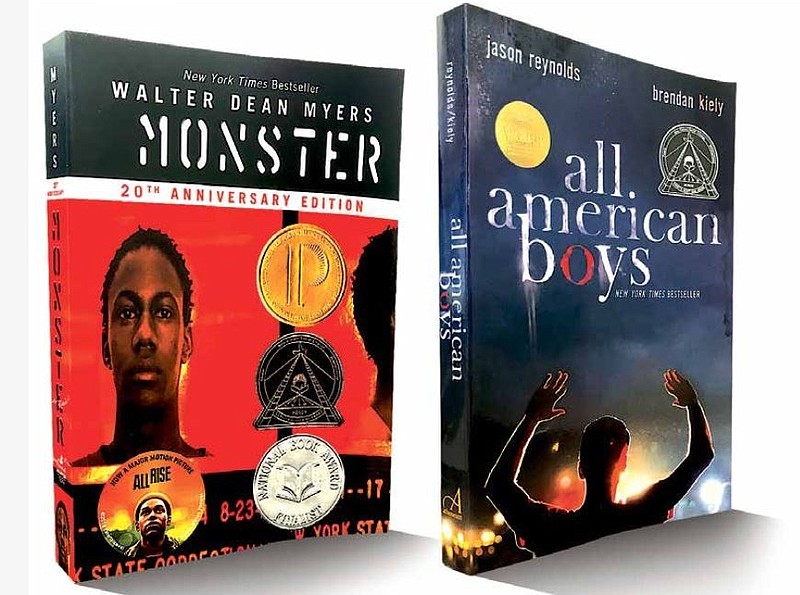

Earlier this week, Monique Brand reported that a middle school English teacher on Signal Mountain removed two novels - Black novels about Black struggles - from her class. Parents had complained.

"The content in the books may be inappropriate for some of our students," the teacher said in an email.

I understand. My kids have encountered novels and movies that created nightmares for them (and us) for a long time. Nobody wants that.

This is not a column about being inappropriate.

It's about being uncomfortable.

We need to be uncomfortable. Like John Lewis' good trouble, we need good discomfort, which shakes and rouses us.

Especially on Signal Mountain.

"Regardless of this perceived book ban, it happens to attach itself onto a long history of oppression, and rejection of the Black community," posted Vanessa Curley, who is white and grew up on Signal. "While the books are fictional, I assure you they are someone's reality off that mountain."

She's right. I know. I grew up there, too. It's my home, my roots. I love so many people there - wise, brave people - and they me.

So I don't write this out of recklessness, but care.

It's time we talk about what we so often avoid:

Being white.

Signal Mountain may make the tops of so many lists: beautiful land, coveted neighborhoods, stellar test scores.

Yet our overwhelming whiteness - 98% white and .04% Black - puts us at the bottom of others.

A 98% white world makes us racially illiterate.

A 98% white world means we can never form the Beloved Community.

A 98% white world is a narcotic.

I say this from the front of the line; no one was more asleep than I. Growing up on Signal Mountain meant I spent years without once questioning or considering my own color.

I lived asleep. I lived a racist life.

I'd learned to forget.

"The forgetting is habit," writes Ta-Nehisi Coates in "Between the World and Me." "They have forgotten the scale of theft that enriched them in slavery; the terror that allowed them, for a century, to pilfer the vote; the segregationist policy that gave them their suburbs. ... [and] to remember would tumble them out of the beautiful Dream and force them to live down here with us, down here in the world."

My grandparents moved to the mountain in the 1950s; that would have never happened if they'd been Black or brown.

Yes, they worked hard, saved, hustled. But had they been Black? They would have lived somewhere else. One simple switch - skin color - and our family's wealth, connections and opportunities would have been completely different. Accumulated mountain wealth is connected to generational poverty in the ghetto.

Living in a 98% white world means I could arrange my entire life - my schedule, my shopping, my recreation, my church-going - so that I never encountered a Black or brown person in any meaningful way. (Or Jew. Or Muslim. Or openly gay.)

Know what began to save me?

Relationships. Friendships.

Formed with the very folks who could not or would not live on Signal.

Let me say clearly: I write this confessing my own double standards, hypocrisies and racism.

I write in thanksgiving of the many people - from mountains to valleys - causing good discomfort already.

Yet I also write with grief.

Here in our 98% white world, we've lost something. Something precious.

Could we join together and create it?

I see BLM signs in many yards. One family created a free library of Black authors. Certain teachers confront racism in the classroom. Real estate agents can become intentional - attracting Black and brown buyers to undo our de facto segregation.

Folks are pushing for the removal of the mountain-front statue of a town founder who chartered a rule forbidding people of color from owning property. It's also time we confront our history of Byron de la Beckwith.

(Next, remove the Confederate general statue outside the county courthouse. Why won't white county commissioners or the white mayor do something? The general fought to enslave the ancestors of the Black commissioners you serve alongside. My God, what are you waiting for?)

Those middle school students? Their parents? We can form our own book club and read banned books that push and make us uncomfortable.

A few years ago, a Black friend challenged me: Why would King include Lookout Mountain in that list? (Lookout, like Signal, is overwhelmingly white.)

I did not have an answer then.

I do now.

I had to get uncomfortable to find it.

David Cook writes a Sunday column and can be reached at dcook@timesfreepress.com.