Point: The 'broccoli of politics' is a healthy habit to embrace

By Nan Hayworth

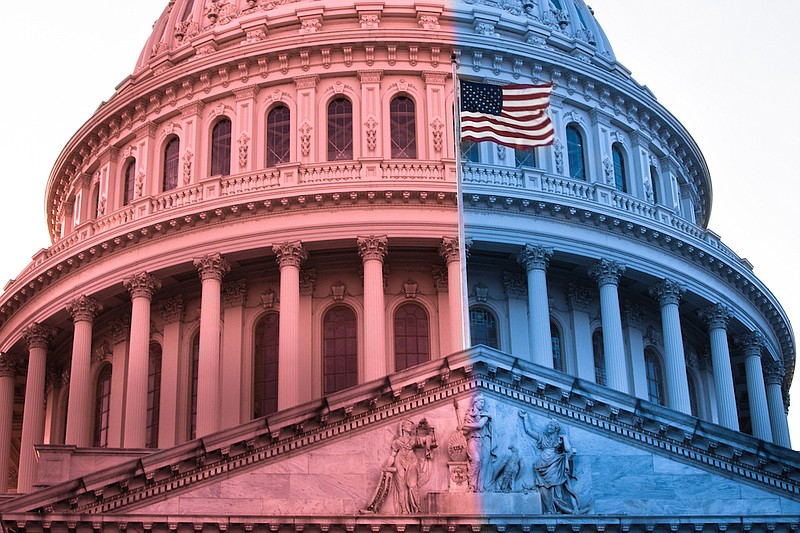

Bipartisanship is the broccoli of politics.

Everyone knows it's good for us, but few of us love it.

When I was elected to Congress in 2010 I became a member of the new House majority, facing a Democratic majority in the Senate and the Obama administration in the executive branch. The only way to pass legislation was through bipartisanship.

In the summer of 2011, Republicans who had been elected in the tea party wave were sorely challenged when it became necessary to raise the ceiling on the national debt. The very idea of countenancing, let alone authorizing, an even more massive burden on American taxpayers, and on successive generations without a vote to weigh in on this depredation against them, was repugnant.

Many of us, including me, had inveighed vehemently in the public record against raising the debt ceiling, and even vowed (ignorance is bliss!) to vote against so doing. But the heady days of campaigning against the leftward juggernaut of the first two Obama years were long over, and, as the grayer (no wonder) heads advised us, we were now obligated to govern.

The relatively small number of House Republicans who represented swing districts were in the best political position, given the composition of our constituencies, to work across the aisle. Mine was one of those districts.

With superb assistance by my legislative team, I hosted a briefing for fellow members to lay out the potentially devastating consequences of even a technical default. We became acquainted with the tough reality that ending the spiral of profligate spending and confiscatory taxation would require finesse and patience - and bipartisanship.

Enough of us came around to pass the package negotiated by teams from the House and Senate majorities and the White House, but not before a contingent of Republicans engendered a last-minute cliffhanger vote that gave us the "sequester" of domestic (a GOP condition) and military (a Democratic condition) expenditures that has vexed both sides ever since.

That, of course, is the essence of compromise, in the immortal words of then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid: "No one got what they wanted, and I always find ... if people walk out of the room and parties are all dissatisfied, that's a pretty good settlement."

In my own frequen discussions of the debt-ceiling deal, I urged the word "cooperation" be used as an alternative to "compromise," because in the latter case everyone loses, but in the former everyone wins.

The vogue for positive thinking about bipartisanship that I hoped this reasoning might inspire failed to materialize. It's the gastronomy of politics: If you go into an election envisioning cake and ice cream, getting broccoli instead feels like a letdown.

Today the palatability of bipartisan compromise is being contemplated afresh, this time by Democrats on whose side the ascendant energy is for radical transformation of our election system, our economy, our energy portfolio and our courts.

And, as in the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis, it falls on those members of Congress and senators whose districts and states are most politically balanced to lead the way forward, with smaller and more gradual steps than their respective parties aspire to take.

While it's true that bipartisan politicians tend to have a particular type of resilience, namely a tolerance for "friendly" fire from their own side, their existence and survival depend almost entirely on who's electing them. West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, the Democrat who has become the de facto leader of the bipartisan coalition on Capitol Hill, represents one of the most Republican states in the country, and that, more than anything else, is what stiffens his spine against his party's leftward lean.

The relevance of the political composition of constituencies acquires extra prominence every 10 years, when congressional district lines are redrawn according to census results. A combination of advancing polarization and gerrymandering, an impulse to which both sides of the political spectrum have understandably yielded, has decimated the bipartisan species over the past couple of decades.

We're in the midst of a redistricting cycle now, and its implications for Washington's behavior will be known in 2022.

In the meantime, a nation whose dessert preference is evenly divided would be well-advised to develop an appreciation for the healthy benefits of broccoli.

Nan Hayworth is a former congresswoman for New York's 19th Congressional District. She is a member of the board of directors at Independent Women's Forum. She wrote this for InsideSources.com.

Tribune Content Agency

Counterpoint: Bipartisanship isn't dead; it just takes political courage

By Andrew Lautz

President Joe Biden promised a new era of bipartisanship when he was elected, telling media in December that "the nation's looking for us to be united, much more united." As any plain observer of the nation's politics can see, partisan tensions are still sky high.

Bipartisanship isn't quite dead yet, but a major way that both parties could earn voters' trust is if they worked together to tackle soaring federal debt and deficits. This may seem counterintuitive, given that the Biden administration has been pointing to strong support in public polls for its big-spending plans. But record levels of federal spending and the budget deficit remain of great concern to voters, and that fact hasn't changed for a decade.

Gallup most recently reported that nearly half of voters worry a "great deal" about federal spending and the budget deficit. An additional 28% worry a "fair amount," meaning more than three-quarters of voters are at least somewhat worried. These numbers are down from the public worry in 2011 (when 87% were worried a "great deal" or a "fair amount") but are high enough that lawmakers should care.

It would be great if lawmakers started by tackling unsustainable growth in mandatory spending (including big-ticket programs like Medicare and Social Security), which makes up 66% of total federal spending in the current fiscal year. These programs are major drivers of spending growth and could be disproportionately responsible for any future debt crisis the nation faces.

Absent a grand bargain on entitlement reform, though, lawmakers must seek smaller but meaningful compromises to reduce the discretionary spending pie that Congress controls. The place to start is the Department of Defense budget.

Why? Defense is the largest single part of the discretionary federal budget, coming in at $715 billion authorized by Congress in the previous fiscal year. Military spending typically makes up more than half of the discretionary budget passed by Congress and is projected to rise to more than $900 billion per year by the end of the decade. And, as is typical with the federal government, military spending is rife with waste, inefficiency and improper allocation of resources.

It's hard to believe, but responsible and meaningful reductions to the military budget were once a bipartisan venture. President Ronald Reagan presided over real military cuts in four of the eight years of his presidency. In 1985 and 1986, Reagan and a divided Congress worked together to enact significant defense cuts of 3.8% and 3.1% respectively (adjusted for inflation), with wide bipartisan margins. The following two years, they agreed to additional, if more modest, cuts.

If Biden and Congress did now exactly what Reagan and Congress did in 1985 or 1986, we would be looking at military spending next year near or below $700 billion - still a staggering sum from which we can more than afford to defend the nation - instead of three-quarters of a trillion dollars.

Of course, Reagan first asked for and received large increases during his first term, and his last Defense Department budget was 7.4% higher than his first. But given that the current Pentagon budget has risen 36% in real terms in the last 20 years, some bipartisan reductions - in the model of the 1980s and 1990s Reagan, Bush and Clinton cuts - are long overdue, especially as the United States ends 20 years of war.

If lawmakers and Biden administration officials can muster the courage to take up reductions in the defense budget, where should they start? A cross-ideological group of civil society organizations and budget experts has a roadmap, outlining up to $80 billion in potential reductions for the coming fiscal year alone. They include sensible recommendations like halting additional purchases of the issue-plagued and tremendously expensive F-35 aircraft (savings of $11.4 billion), reducing wasteful service contracting by 15% (savings of $28.5 billion), and canceling the Ford-class aircraft carrier (savings of $12.5 billion per carrier).

Military hawks will complain that cuts will make us less well-positioned to take on foreign adversaries like China and Russia - as they complained about Reagan's proposed military budgets during the Cold War.

Simply put, Congress and the Biden administration can afford to make modest, bipartisan reductions in the defense budget.

Andrew Lautz is the director of federal policy for National Taxpayers Union. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.

Tribune Content Agency