(Editor's note: First of two parts)

According to a national poll, registered nurses are the most trusted professionals in the United States. Nurses' heroic efforts during the current pandemic will likely further their reputation as trusted and respected professionals.

Before the end of the 19th century, a nurse was anyone who cared for the sick. During the Civil War, many Chattanooga women and men tended the wounded, both Union and Confederate, who flooded into the city following area battles. Historian Zella Armstrong in her 1931 book, "A History of Hamilton County and Chattanooga Tennessee," lists 40 prominent women and a number of men who volunteered to nurse the sick and wounded.

Their number included Ella Newsome, a wealthy widow, who opened a 700-bed hospital to care for the casualties. Nurses trained in the field while working with doctors and more experienced volunteers. Some of these courageous volunteers gave their lives caring for the wounded. They included Elizabeth Anderson McFarland of Rossville, who died of "camp fever" in 1863.

The same was true during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878. Believing the mountains offered protection from the disease, most people left the city. However, some stayed behind to nurse the sick and comfort the dying. They included several ministers: Rev. John Bachman, Fr. Henry Sneed, and Fr. Patrick Ryan, who died of Yellow Fever. Chattanooga High School English teacher, Hattie Ackerman, also volunteered to remain in the city. She contracted the disease and soon died. The city eventually purchased a headstone, located in the Forest Hills Cemetery, honoring her sacrifice.

By the 1880s, Chattanooga was a fast-growing city. Many entrepreneurs, merchants and laborers came to make their fortunes. New railroad lines moved people and material around the city. However, the city did not have a hospital. Several attempts were made to open one, but they soon closed. The closest thing to a hospital was the Poor House located on Highland Park Avenue, between Vine and Fifth streets.

Most people were nursed at home by family members. Indeed, only about 10% of the sick and injured went into a hospital. Babies were born at home, and operations were performed on kitchen tables. (Life expectancy was 47 years and the maternal/infant death rate was about 25%.) Only those who lacked families and the poor went to a hospital. Conditions there were often horrendous, with no trained nurses to ease the suffering.

Florence Nightingale, an English social reformer and statistician, is credited with professionalizing the practice of nursing. Rejecting the traditional roles of wife and mother, she trained at a clinic in Germany. By 1844, she was the superintendent of a London women's hospital. However, it was her work improving the care of soldiers during the Crimean War that introduced professional nursing to the world. Nightingale wrote the first nursing textbook and The Florence Nightingale Nursing Pledge, providing a code of ethics for nursing practice. Her pledge is recited by nursing graduates to this day.

Nightingale's work led to the founding of nursing schools in the United States and Europe.

Chattanooga's first professional nurse was Lucy Wissmann. A graduate of the German Deaconess Hospital School of Nursing in Dayton, Ohio, she came to Chattanooga in 1895. She was employed as a surgical nurse by Dr. Henry Berlin. Following his death in 1916, she became a much sought-after private duty maternity and baby nurse. Over the course of her career she cared for 336 babies and their mothers. Pictures of "her babies" adorned the walls of her Barton Avenue home until her death at age 97.

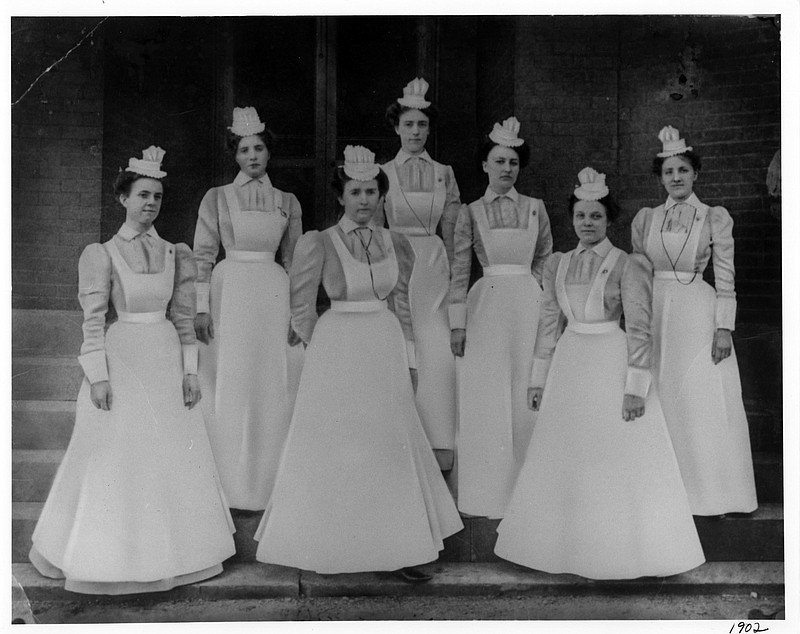

The 72-bed Baroness Erlanger Hospital opened in July, 1899. The Erlanger School of Nursing was established in the same year. One of the first nursing schools in the state, five young, unmarried women comprised the first class. The first graduates completed their two- year training in 1901.

Nurses at this time were responsible not only for basic nursing care, but also many housekeeping duties. Many procedures now common in nursing, for instance, obtaining blood pressure readings, were left to physicians. Operating room nurses maintained antiseptic conditions, prepared the patient for surgery, and often administered anesthesia.

By 1905, 21 nurses had graduated from the Erlanger School of Nursing. Students and graduate nurses were expected to maintain high standards of cleanliness, neatness and moral character. Their white uniforms included starched aprons and their school's distinctive cap.

Gay Moore, a registered nurse, is the author of two books and numerous articles on Chattanooga history. For further information visit chattahistoricassco.org.