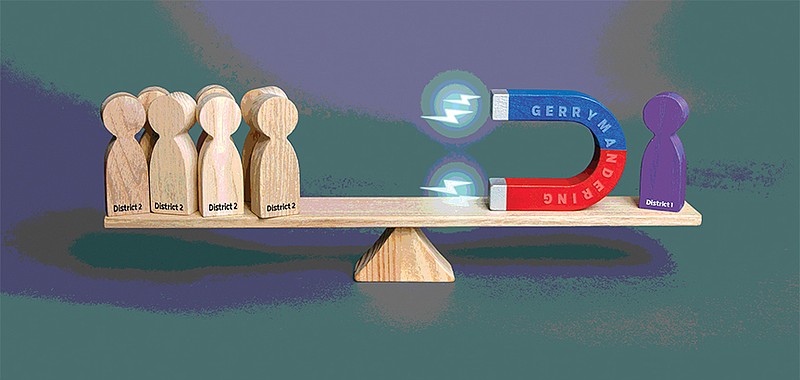

POINT: Gerrymandering is inevitable in a democracy

By Hans von Spakovsky

With the Census Bureau finally releasing its population data to the states, the process of redrawing political boundaries for local, state and congressional seats begins. Anyone who believes that there is some magic way of keeping politics out of the redistricting process must still believe in the tooth fairy.

In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan redistricting - where elected representatives from the majority political party draw boundary lines to try to give their party an advantage - is a political question beyond the reach of the federal courts. Moreover, the court pointed out that partisan redistricting is "nothing new."

It was known "in the colonies prior to independence and the framers were familiar with it at the time of the drafting and ratification of the Constitution," said the court. In fact, the term "gerrymandering" comes from Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry, whose name is forever linked to partisan map drawing due to a state senate district he drew in 1812 that looked like a salamander.

Yet the drafters of the Constitution still gave state legislatures the authority to draw congressional boundaries, showing that they expected politics to be part of redistricting. Partisanship is considered a dirty word today, but partisanship is defined by the views and opinions that individuals - and the political party they favor - have about history, culture, society, politics and public policy.

Imposing a rule that legislators cannot take those interests into account - and the interests of the voters who elected them - when drawing political boundaries would destroy a fundamental element of our democratic system. Politics will always play a role in redistricting.

And why shouldn't it? Politics is involved in who runs for office, who voters choose to represent them, and what those candidates do once they get into office. There really is no way to keep political considerations out of redistricting. Indeed, there are strong arguments against trying to do so.

One thing we know - partisan redistricting is a very inexact science because American voters are unpredictable, no matter what political consultants may tell you. Additionally, we only redistrict every 10 years, and the makeup of districts can change very quickly because we are a highly mobile society. Thus, there are examples of supposedly "safe" districts at all levels - local, state and federal - being drawn for one political party that have been won by the opposition party.

There are also examples of another American phenomena that makes effective partisan line drawing difficult - the tendency of many voters to split their tickets between candidates of different political parties, depending on whether they are voting for their local city council member, their congressional representative or the president of the United States.

Some believe we can take politics out of the redistricting process by establishing so-called "independent" redistricting commissions that take the power to draw political lines away from state legislatures. All this does is move the politics and partisanship behind closed doors. Such commissions, whose members are chosen by the political parties and other government officials, are inevitably made up of individuals with partisan interests, despite their public assertions to the contrary.

As a 2019 analysis by the Capital Research Center showed, California's "independent" redistricting commission actually drew more partisan congressional districts than the partisan Republicans controlling the Texas state legislature did. And what's worse, such commissions are unaccountable to the people.

Voters who are unhappy with the districts drawn by legislators, county commissioners or city council members can vote them out of office. Voters can't do that to appointed commissioners who draw partisan districts that voters don't like.

You can't take politics out of redistricting, but you can implement common-sense rules that prevent misshapen districts that you need a GPS to navigate. Those rules should require that districts be as compact and contiguous as possible. They should follow the lines of natural boundaries like rivers and mountains and political boundaries like city and county lines. That will also lead to representatives who have an interest in representing all of the diverse people of a city, for example, rather than just those who are concentrated in one part of that city.

For more than 200 years, Americans have complained about partisan gerrymandering. But that is how our system works, and despite all of the complaints, we have something many other people around the world envy: a remarkably stable system of governance in which our democracy has never been compromised.

Hans von Spakovsky is a senior legal fellow and manager of the Election Law Reform Initiative at the Heritage Foundation. He is the co-author of the soon to be released book "Our Broken Elections: How the Left Changed the Way You Vote." He wrote this for InsideSources.com.

Tribune Content Agency

COUNTERPOINT: Scrap gerrymandering and adopt ranked choice voting

By Rob Richie and David Daley

Partisan gerrymandering of legislative districts has been a uniquely American problem since our founding: As long as we've had politicians, they've exploited the power to pick their own voters before the voters get to pick them.

It's wrong, and it's getting worse. Politicians have fancier tools and greater incentives to draw maps that advantage their side. More than ever, gerrymanders - crafted with sophisticated technology, powerful software, and terabytes of personal and political data - threaten the powerful ideals at the heart of our Founders' vision: Consent of the governed.

Citizens in a representative democracy must have the power to change their leaders when they so desire. But after the 2018 midterms, 59 million Americans lived in a state where a legislative chamber was controlled by a party that lost the popular vote.

Our reform priorities are skewed. We must prevent voter fraud, but it's as rare as being struck by lightning. Meanwhile, twisted maps alter politics nearly everywhere.

As the 2021 redistricting cycle begins, and politicians lock themselves in back rooms in order to lock voters out of power for another decade, it's clear that something must be done. But what solution will truly work - and last?

John Adams said that legislatures ought to be "in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason and act like them." That's a tough claim to make about our polarized Congress: A recent Economist poll found that Congress has a 17% approval rating.

Partisan redistricting is a problem, but the root cause is districting itself. Right now, we elect 435 members of Congress from 435 single-member districts. The shape of each district matters so much because most of the nation tilts distinctively red or blue. The best way to flip a seat is to control redistricting, not change voters' minds.

Virginia Congressman Don Beyer offers a comprehensive solution: the Fair Representation Act. It would replace our winner-take-all district system - one formalized with an act of Congress only 54 years ago - with a fair approach for all states: Larger districts represented by multiple representatives elected proportionally with ranked-choice voting.

This would upend the power of gerrymandering. All of the things people hate about gerrymandering - few competitive districts, greater partisan rigidity when safe seats move all the action to low-turnout party primaries, skewed outcomes - would go away.

Better still, the results would be fairer. Take Massachusetts. Donald Trump won 32% of the vote there, and the Republican governor is one of the nation's most popular. You might assume that Republicans have three of the state's nine congressional seats. Yet Massachusetts voters have not sent a single Republican to the House since 1994.

Under the Fair Representation Act, Massachusetts would have three districts with three members, and Republicans would likely elect one seat in each. Fair representation also would be true for underrepresented Democrats in Tennessee, Kentucky, Kansas and Oklahoma - all of whom are now in danger of being gerrymandered into extinction through gerrymandering.

Every state would have the same number of representatives. We'd simply elect them in a way that creates a closer replica of the people, as modeled in many local elections.

Some states have tried to address gerrymandering with commissions. But they can prove vulnerable to partisan manipulation, and wouldn't have much effect in states like Massachusetts or Tennessee where political geography makes it impossible to draw competitive single-member districts that accurately reflect the people.

The U.S. Constitution may not dictate proportionality, but Americans feel it deeply: We know that 60% of the vote shouldn't equate to 100% of the seats. Winner-takes-all districts are the reason Congress doesn't mirror the people or govern according to their desires.

A proportionally elected House would not only fulfill a deeply American vision of equality, but help parties represent their "big tents," incentivize cooperation, and give everyone a voice without hijacking majority rule. Independents would be able to hold the major parties accountable without splitting the vote. Minority voting rights would be reliably protected, and women would gain new opportunities to level the playing field. Everyone would have the voice they win at the polls, no less and no more.

Incentivizing our politicians this way would be the most meaningful change we could make to address gerrymandering, and also to make a broken Congress function again.

Rob Richie is president and CEO of FairVote, a nonpartisan organization seeking better elections. David Daley is senior fellow at FairVote and author of "Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy." They wrote this for InsideSources.com.

Tribune Content Agency