Regarding statues, monuments and other public tributes to those once deemed great - which to do away with and which to keep - four familiar words can guide our choices: a more perfect union.

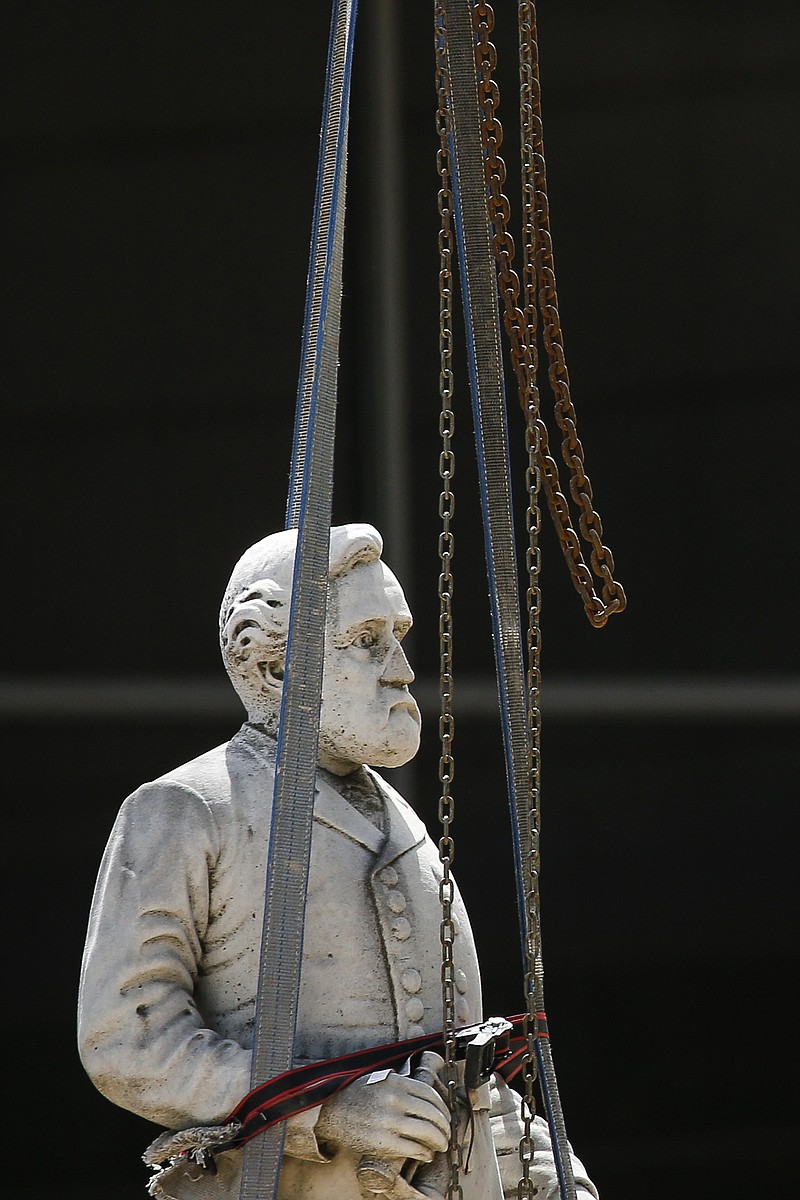

Did Jefferson Davis or Robert E. Lee fight for a more perfect union? No. They fought for disunion. Outside of museums, gravesites or private collections, there should be no statues of either man, or of their senior confederates.

Likewise, John C. Calhoun believed in slavery as a positive good and nullification as a state's right. He utterly fails the more perfect union test, which is why Yale was right when in 2017 it rechristened the residential college previously named for him.

Likewise, Forts Bragg, Hood, Benning and seven other military installations named for Confederate generals should be renamed. The Constitution is specific in defining treason narrowly as "levying war" against the United States. It is dangerous for the government to name buildings or facilities for those who betrayed it - and incredible that the fact escaped wide notice until now.

Likewise, we should never honor public figures who, by the standards of their own time as well as ours, abused a public trust. Case in point: The more we learn about J. Edgar Hoover, the more outrageous it is that the FBI building in Washington is still named for him.

These are the easy cases. Equally easy are the opposite cases.

Hans Christian Heg, an ardent abolitionist whose statue in Madison, Wisconsin, was pulled down last week, fell at the Battle of Chickamauga trying to make a more perfect union. Robert Gould Shaw, who commanded one of the first Black Union regiments and whose monument in Boston was defaced last month, was killed at Fort Wagner trying to make a more perfect union. Ulysses Grant, who did more than any other general to defeat the Confederacy and more than any other president to defeat the Klan, and whose statue in San Francisco was pulled down earlier this month, devoted his life to trying to make a more perfect union.

What about, say, Andrew Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson or George Washington?

The central case against Washington and Jefferson is that they were slaveholders, albeit ones who knew slavery was wrong. If their fault lay in being creatures of their time, their greatness was in their ability to look past it.

An unbroken moral thread connects the Declaration of Independence to the Gettysburg Address to Martin Luther King's "I Have A Dream" speech. An unbroken political thread connects the first president to the 16th to the 44th. It's impossible to imagine any union, much less the possibility of a more perfect one, without them.

Jackson and Roosevelt? Both were avowed racists, and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, enacted during Jackson's presidency, stands with the Chinese Exclusion Act as one of the most shameful pieces of American legislation.

But there's historical irony in the fact that some of today's progressives are eager to bring down statues to the two most progressive presidents of their times. Roosevelt busted trusts, championed conservation and caused a scandal by inviting Booker T. Washington to dine with his family in the White House. Were those not acts in the service of a more perfect union?

As for Jackson, his egalitarianism, distrust of big money and battle with Calhoun over nullification make him much more the political progenitor of Bernie Sanders than of Donald Trump. If it's okay to knock Old Hickory off his pedestal now, is any reformist leader of the more recent past - FDR, for instance, or even Barack Obama - safe from the furies of the future? It's hard to build progressive politics on a continually undermined foundation.

That isn't to say that every statue is worth preserving. New York's Museum of Natural History decided to bring down the equestrian bronze of the 26th president, not so much on his account as because of the placement on his flanks of a Native American and an African figure. Fine. But since the museum is largely dedicated to Roosevelt's legacy as a statesman, scholar and naturalist, isn't the right way to do it to replace it with another T.R. statue - this time as a man in the arena rather than as a figure in the saddle?

Such a statue might be a useful reminder that the men and women who most deserve to be shaped in metal or carved in stone weren't made from them. And that acknowledging the fallibility of our national heroes and the limitations of their time needn't make them less heroic and may often make them more. And that there's a vast difference between thinking critically about the past, for the sake of learning from it, and behaving destructively toward the past, with the aim of erasing it.

A great debate about who should remain on which pedestals can be a healthy one. The right's idea that we must preserve the worst figures to protect the best is idiotic. The left's idea that we should bring down the best because we know who they were at their worst is no less so.

An intelligent society should be able to make intelligent distinctions, starting with the one between those who made our union more perfect and those who made it less.

The New York Times