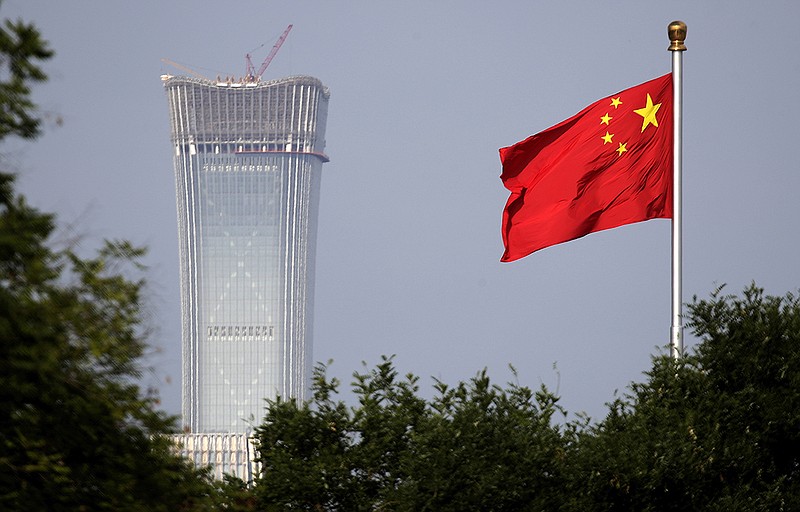

Religious freedom was written into the Chinese constitution in 1982, but in a communist country it is just a concept signifying nothing.

Word lately has come through WND of Chinese President Xi Jinping's crackdown on Christian believers there. The actions by Xi, said to be the country's most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, are said to be a broader push by the leader to infuse the nation's religions with "Chinese characteristics," particularly loyal to the Communist Party, according to an Associated Press report.

Since Christianity brooks no split loyalties, a clash was inevitable. The winner also is certain. Of that Christians are assured. But that doesn't mean there won't be turmoil.

The faith, according to Operation World, has some 105 million adherents in the country, nearly 8 percent of its population, and is growing. Many of those attend illegal or "unregistered" house churches.

A friend and former colleague of this writer ran one for a time during a period in the last 10 years. The interest in Christianity, he reported, was palpable.

However, many of those house churches have been shut down in recent months, and many others have reported "unprecedented" harassment since February, it has been reported.

The Chinese government in recent years had permitted smaller such gatherings but was sporadic in its allowing some to continue and not others. But this year, according to the AP, the persecution has intensified amid a campaign of "thought reform."

Last November, according to the South China Morning Post, communist officials visited the homes of some Christians in the Jiangxi province and suggested they replace personal religious displays with posters of President Xi. Many complied.

The country, its president said in 2016, "must resolutely guard against overseas infiltrations via religious means."

Earlier this year, according to Christianity Today, the Chinese government laid down new regulations that required religious groups to obtain government approval for any religious activity. Those activities include studying theology, publishing religious materials, calling oneself a pastor and using one's personal home for meetings.

The Bible, for example, according to the New York Post, has been banned from being sold online in the country. It already had been banned from being sold at traditional bookstores and could only be sold at religious bookstores. Taoist, Buddhist and Muslim religious books were still OK but not the Bible.

In one province, between 2014 and 2016, 1,500 crosses were removed from churches.

Further, where a distinction once existed between government-registered and unregistered churches, according to Open Doors, now no such distinction exists.

"All Christians are slandered," the report said, "which seems to support the widely held belief that the Communist Party is banking on a unified Chinese cultural identity to maintain its power."

Under Mao and during the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1976, the government completely banned religious life. Amid economic reforms, the government-controlled Protestant Three-Self Movement was restored in 1979, and in 1980, the China Christian Council was established as an umbrella organization for all Protestant churches.

But Christian faith, thought to have been introduced in the country as early as the seventh century, isn't contained in movements and organizations but in the hearts of those who believe. So it will survive the reign of Xi just as it did the reign of Mao.

Many Americans, Chinese and Christians in other countries have recounted the efforts to literally keep the faith during its previous darkest years of suppression.

Liao Yiwu, for instance, writes of the Protestant minister, ultimately buried in Westminster Abbey, who was executed during the Cultural Revolution as "an incorrigible counterrevolutionary"; the nun, now more than 100 years old, who persevered in spite of beatings, famine and decades of physical labor, and still fights for the rightful return of church land seized by the government; and the surgeon who gave up a lucrative Communist hospital administrator position to treat villagers in the remote, mountainous regions of southwestern China.

No matter what extremes Xi plans to go to about Christianity, it will survive. Secret house churches will still hold worship, Bibles will still be smuggled in and hearts will still search for something, unlike Marxism, that is alive.

One township committee officer told the AP the government's "thought reform" is working on "Christian families in poverty" who are being educated "to believe in science and not in superstition, making them believe in the party."

Ultimately, that won't work, because the heart desires something more.

"After the collapse of communist ideology," Zhang Lijia, a prominent Chinese writer, told the AP, "no value system has been in place to fill the spiritual vacuum. China has witnessed a religious revival in recent decades precisely because of this vacuum."

Religious freedom may be written into the Chinese constitution, and could be removed, but religion in the hearts of the Chinese people can never be erased.