It's Veterans Day. That, you know.

But, increasingly, we may forget the day set aside to honor living and dead veterans in the United States is what for many years was called Armistice Day because it is the day hostilities ceased between the allied powers and Germany in World War I.

Precisely, the armistice took effect at the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918, 100 years ago today.

View our 21 Veteran Salute page

View our 21 Veteran Salute pageArmistice Day became a legal holiday in the United States in 1938, ironically a year before a second world war broke out and swept across Europe. Congress changed the name to Veterans Day in 1954.

In 1918, it was a Monday, that Nov. 11.

On that day, Robert Sparks Walker, a Chattanooga author and naturalist and the founder of what became known as Audubon Acres, was in his 16th year as editor and publisher of the Southern Fruit Growers paper on Chestnut Street.

"Such a world of confusing and shouting!" he wrote of the local celebration. "People went wild over news of victory over Germany. Junk piles, long dead and voiceless, suddenly sprang to life as if by magic; items rusty, battered, split, spoke with a glib tongue, clanging, banging, dragging, a shrieking mass of old kettles, dishpans, crosscut saws, washpots, sledge hammers, lard cans, and other devices from the garbage. Every conceivable noise-producing object was pulled from its hiding place and brought onto the streets throughout the day, the noise equal to a parade. Screams of joy rang wildly, and booming firearms beat upon human ears."

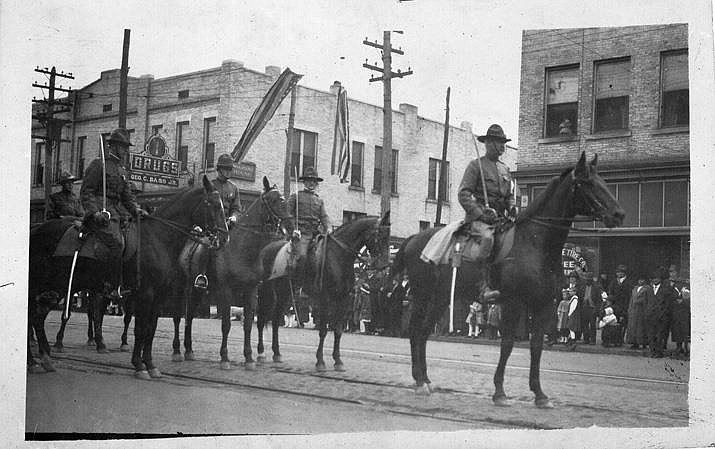

A photograph of the throng on Market Street appears in the book "Fort Oglethorpe" by Gerry Depken and Julie Powell. Civilians and soldiers from several Army units training in Fort Oglethorpe join in what appears to be a mass of hundreds of people.

"Flags waved, and spectators crowded the sidewalks and hung out of windows as they joined in the gaiety," a caption under the photo reads.

One of those who'd been stationed in Fort Oglethorpe only months before was then-Capt. Dwight Eisenhower, who had been itching for a combat assignment in the war but was deemed too valuable as an instructor to leave his job and go abroad.

"This was distressing," he wrote in "At Ease: Stories I Tell To Friends," a 1967 memoir. "I wanted to stay with a regiment that would see action soon. Luckily, over the months I had been following the progress of the war and read everything that I could find about minor tactics of infantry."

Months before Armistice Day, the camp at which he was assigned closed, and he moved on but never saw combat in Europe. However, the theories of which he read would serve him well as supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe during World War II.

A regular soldier who remained and was stationed at one of the Fort Oglethorpe camps was Ralph Baird, a Kansas native.

"We did everything," he told historian Joe L. Todd in 1985. "I woke up in the middle of the night and there was celebrating everywhere. The next day we didn't drill, and we didn't do anything, we were celebrating."

The Chattanooga News of Nov. 12, 1918, described the scene:

"The big celebration on Market Street continued late Monday night, dwindling slowly away near midnight," it said. "It is probable that the bedlam would not have ceased then had not the crowds been fatigued by their all-day merry-making.

"Along about eight or nine o'clock the carnival spirit which had pervaded the mob during the day began to merge with a spirit of rowdyism which had been steadily coming to the front. For a time it was feared that as the crowd got rougher and rougher there would be serious consequences, but nature took her course and many people left early to go to bed."

The end of the war, of course, was reason enough to celebrate. But less than two weeks earlier, the city - and the nearby Army camps, as well as the nation - was seeing the end of a Spanish flu epidemic the likes of which the country had not seen in many years.

The epidemic claimed, according to Times Free Press archives, nearly 700 in Chattanooga and Hamilton County and some 400 at military posts.

Across the country, the flu claimed some 675,000. The war would kill 110,000.

Over the 19-plus months of U.S. involvement, about 5,000 Hamilton County residents served in the war. Of those, according to newspaper archives, 117 died, including at least 64 from disease. Four of the dead were killed within the two weeks of the armistice being signed.

For a war that began with the shooting death of a minor European archduke, a war the U.S. steadfastly tried to stay out of for nearly three years, World War I served to move the country into a dominant position on the world stage.

It became an indispensable player in terms of power and might but also in its ability to help shape the peace. Some, but not all, subsequent wars and U.S. skirmishes, and those where the U.S. was not a player in the conflict but in the resolution, bear that out.

Today, at 11 a.m., bells will ring in some Chattanooga churches and elsewhere across the country, in commemorating the end of World War I. As they do, we should ponder the responsibility the U.S. still has - 100 years later - as a powerful global leader but also as an instrument of peace.